Zululand - history.

Publié le 26/05/2013

Extrait du document

«

however, and had to be satisfied with constant raids and with the payment of tribute.

Defeated or terrified chiefdoms who attempted to move out of the range of the Zuluarmies added to the general confusion and devastation of southeastern Africa.

In 1824 a small British trading settlement was established at Port Natal (later Durban), which fatefully connected Zululand to the colonial world.

Shaka welcomed the Britishhunters and traders as suppliers of exotic goods and, because they had firearms, as mercenaries in his wars.

In return he permitted them to live peacefully at Port Natal likechiefs living in his kingdom under his overlordship.

IV ARRIVAL OF THE AFRIKANERS

Resistance to Shaka’s unending military campaigns and high-handed style of rule grew in the 1820s.

In 1828 a trusted adviser and two of Shaka’s half-brothersassassinated him.

One of the conspirators, Shaka’s half-brother Dingane, swiftly killed almost all of his rivals in the royal house and brutally established his authority.

UnlikeShaka, Dingane was suspicious of the British presence in Port Natal, which was growing in size and independence.

However, the greater threat came from over theDrakensberg Mountains to the west.

In October 1837 Dutch-speaking Afrikaners (or Boers , Dutch for “farmers”) began emigrating across the Drakensberg Mountains into the Zulu kingdom.

These emigrants, known as Voortrekkers , requested permission from Dingane to settle in Zulu territory south of the Thukela River.

Aware that the same group of Voortrekkers had recently defeated a powerful nearby state, Dingane feared that the Afrikaners would overrun Zululand.

In February 1838 Dingane invited their leader, Pieter Retief, and a party of hisfollowers to his homestead to negotiate.

There, Dingane had the Voortrekker party massacred.

He simultaneously sent his armies to attack the Voortrekkers’ encampments.After an indecisive series of battles, the Voortrekkers avenged the massacre by defeating the Zulu army on December 16, 1838, at the Battle of Blood River, also known asthe Battle of Ncome River.

V FALL OF THE ZULU KINGDOM

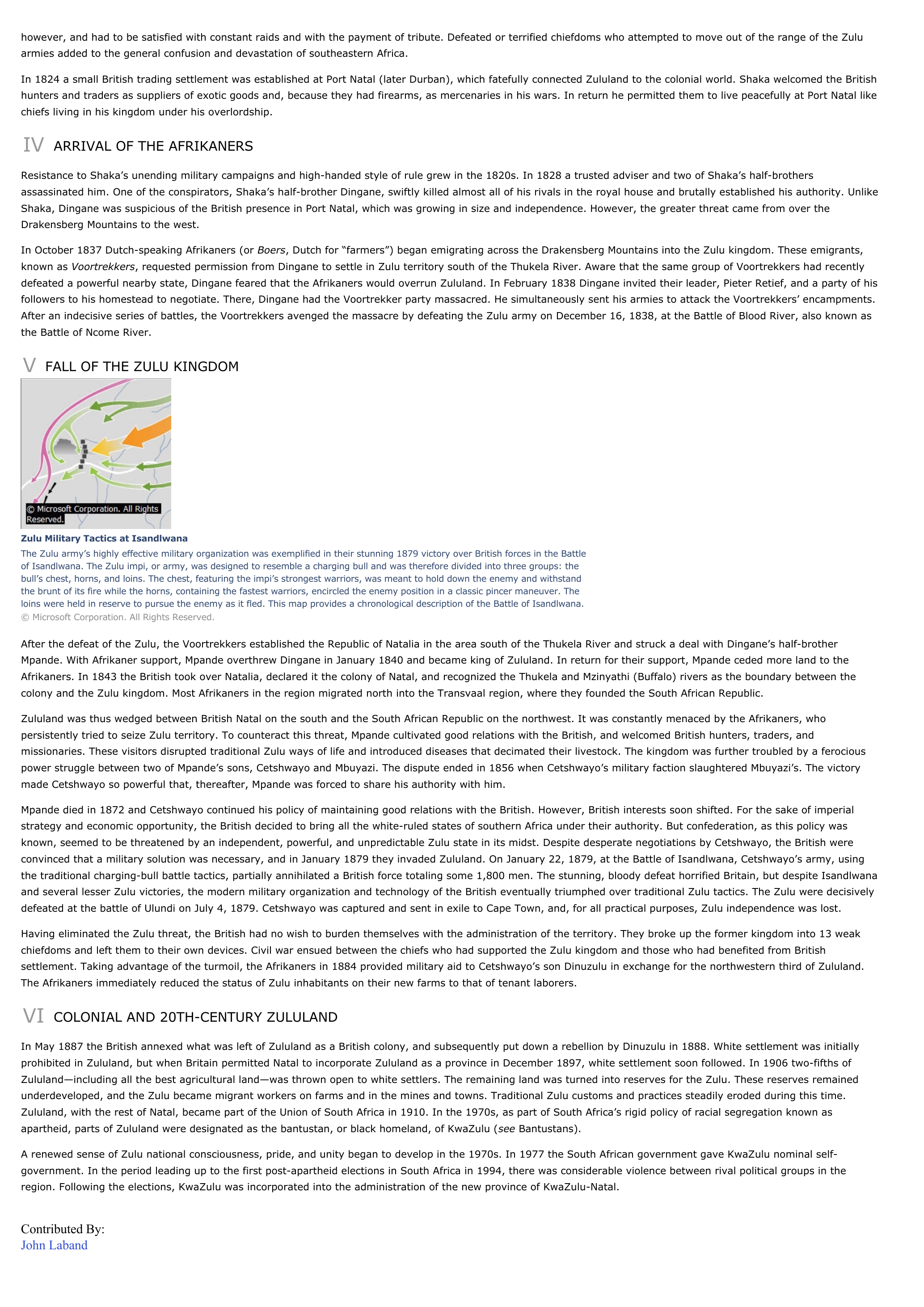

Zulu Military Tactics at IsandlwanaThe Zulu army’s highly effective military organization was exemplified in their stunning 1879 victory over British forces in the Battleof Isandlwana.

The Zulu impi, or army, was designed to resemble a charging bull and was therefore divided into three groups: thebull’s chest, horns, and loins.

The chest, featuring the impi’s strongest warriors, was meant to hold down the enemy and withstandthe brunt of its fire while the horns, containing the fastest warriors, encircled the enemy position in a classic pincer maneuver.

Theloins were held in reserve to pursue the enemy as it fled.

This map provides a chronological description of the Battle of Isandlwana.© Microsoft Corporation.

All Rights Reserved.

After the defeat of the Zulu, the Voortrekkers established the Republic of Natalia in the area south of the Thukela River and struck a deal with Dingane’s half-brotherMpande.

With Afrikaner support, Mpande overthrew Dingane in January 1840 and became king of Zululand.

In return for their support, Mpande ceded more land to theAfrikaners.

In 1843 the British took over Natalia, declared it the colony of Natal, and recognized the Thukela and Mzinyathi (Buffalo) rivers as the boundary between thecolony and the Zulu kingdom.

Most Afrikaners in the region migrated north into the Transvaal region, where they founded the South African Republic.

Zululand was thus wedged between British Natal on the south and the South African Republic on the northwest.

It was constantly menaced by the Afrikaners, whopersistently tried to seize Zulu territory.

To counteract this threat, Mpande cultivated good relations with the British, and welcomed British hunters, traders, andmissionaries.

These visitors disrupted traditional Zulu ways of life and introduced diseases that decimated their livestock.

The kingdom was further troubled by a ferociouspower struggle between two of Mpande’s sons, Cetshwayo and Mbuyazi.

The dispute ended in 1856 when Cetshwayo’s military faction slaughtered Mbuyazi’s.

The victorymade Cetshwayo so powerful that, thereafter, Mpande was forced to share his authority with him.

Mpande died in 1872 and Cetshwayo continued his policy of maintaining good relations with the British.

However, British interests soon shifted.

For the sake of imperialstrategy and economic opportunity, the British decided to bring all the white-ruled states of southern Africa under their authority.

But confederation, as this policy wasknown, seemed to be threatened by an independent, powerful, and unpredictable Zulu state in its midst.

Despite desperate negotiations by Cetshwayo, the British wereconvinced that a military solution was necessary, and in January 1879 they invaded Zululand.

On January 22, 1879, at the Battle of Isandlwana, Cetshwayo’s army, usingthe traditional charging-bull battle tactics, partially annihilated a British force totaling some 1,800 men.

The stunning, bloody defeat horrified Britain, but despite Isandlwanaand several lesser Zulu victories, the modern military organization and technology of the British eventually triumphed over traditional Zulu tactics.

The Zulu were decisivelydefeated at the battle of Ulundi on July 4, 1879.

Cetshwayo was captured and sent in exile to Cape Town, and, for all practical purposes, Zulu independence was lost.

Having eliminated the Zulu threat, the British had no wish to burden themselves with the administration of the territory.

They broke up the former kingdom into 13 weakchiefdoms and left them to their own devices.

Civil war ensued between the chiefs who had supported the Zulu kingdom and those who had benefited from Britishsettlement.

Taking advantage of the turmoil, the Afrikaners in 1884 provided military aid to Cetshwayo’s son Dinuzulu in exchange for the northwestern third of Zululand.The Afrikaners immediately reduced the status of Zulu inhabitants on their new farms to that of tenant laborers.

VI COLONIAL AND 20TH-CENTURY ZULULAND

In May 1887 the British annexed what was left of Zululand as a British colony, and subsequently put down a rebellion by Dinuzulu in 1888.

White settlement was initiallyprohibited in Zululand, but when Britain permitted Natal to incorporate Zululand as a province in December 1897, white settlement soon followed.

In 1906 two-fifths ofZululand—including all the best agricultural land—was thrown open to white settlers.

The remaining land was turned into reserves for the Zulu.

These reserves remainedunderdeveloped, and the Zulu became migrant workers on farms and in the mines and towns.

Traditional Zulu customs and practices steadily eroded during this time.Zululand, with the rest of Natal, became part of the Union of South Africa in 1910.

In the 1970s, as part of South Africa’s rigid policy of racial segregation known asapartheid, parts of Zululand were designated as the bantustan, or black homeland, of KwaZulu ( see Bantustans).

A renewed sense of Zulu national consciousness, pride, and unity began to develop in the 1970s.

In 1977 the South African government gave KwaZulu nominal self-government.

In the period leading up to the first post-apartheid elections in South Africa in 1994, there was considerable violence between rival political groups in theregion.

Following the elections, KwaZulu was incorporated into the administration of the new province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Contributed By:John Laband.

»

↓↓↓ APERÇU DU DOCUMENT ↓↓↓

Liens utiles

- Ideology and Rationality in the History of the Life Sciences

- HISTOIRE DU RÈGNE DE L'EMPEREUR CHARLES-QUINT [The History of the Reign of the Emperor Charles V].

- HISTOIRE DU MONDE [History of the World].

- GRANDISON (L') [The History of sir Charles Grandison]. (résumé)

- Robin George Collingwood, The Ides of History, 1946, Oxford University Press, 1994, p. 429 sv., trad. pers.