Shang Dynasty - history.

Publié le 26/05/2013

Extrait du document

«

dependents, and sacrificial victims lay among and beyond the buildings.

The Xiaotun settlement was linked to a complex of settlements and craft centers bordering thefoothills of the Taihang Shan to the west.

The absence of a wall around the site suggests the Late Shang kings were confident they could defend their settlement againstattacks from outsiders.

On the north side of the Huan River, a Shang cemetery at Xibeigang contains the burial pits of eight of the last nine Shang kings.

(Another tomb was evidently underconstruction when the last Shang king, Di Xin, was defeated by the Zhou.) These impressive burial pits were configured with entrance ramps oriented to the four cardinaldirections.

The ramps led to a deep vertical shaft that contained a wooden burial chamber.

The rich grave goods in these tombs had all been looted by the timearchaeologists discovered the site in the 1930s.

The only royal tomb found completely intact in the Anyang area, and the only one whose occupant has been positivelyidentified, is that of Wu Ding’s consort, Fu Hao.

Her tomb was excavated in 1976.

Although much smaller than the royal burials at Xibeigang, it offers a glimpse of how theothers would have been furnished with a lavish assortment of cast bronzes (vessels, bells, mirrors, and weapons), carved jade ornaments, pottery, and objects made ofivory and marble.

The Anyang sites are the only major source of the Shang oracle-bone inscriptions.

The largest and most varied group of divination inscriptions was discovered at Xiaotun in1936.

These inscriptions were primarily from the reign of Wu Ding, who died in about 1189 BC.

The Late Shang inscriptions recorded the king’s divinations on topics such as sacrificial offerings, divine assistance, military campaigns, settlement building, the weather,hunts, harvests, sickness, childbirth, and dreams.

The king began his divination by proposing a specific prediction, such as “Today it might rain” or “The western lands willreceive harvest.” His diviners, or ritual assistants, then applied intense heat to a specially prepared cattle scapula (shoulder blade) or turtle shell.

The heat produced stresscracks that the king’s diviners interpreted as either lucky or unlucky.

The king would then forecast what the future was likely to bring.

Scribes carved a record of thedivination topic, usually prefaced with the date of the divination, into the bone or shell.

Sometimes they recorded the king’s forecast and the eventual result.

The Shang alsocast a small number of inscriptions, usually brief records of ritual matters, into their bronze vessels.

Other Shang records undoubtedly existed, but they would have beenwritten on perishable materials such as bamboo and silk.

III POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS

The Late Shang inscriptions portray a relatively weak dynastic state.

The king presided over a rudimentary administrative hierarchy.

His control over local lords and chiefswas often uncertain because it was exercised through a shifting network of alliances and required backing by military force.

When the king patrolled and hunted in hisdomains, his presence reminded those in outlying areas of his power and of their obligations to him.

The kingship passed from brother to brother or from father to son, with father-to-son descent becoming the rule for the last five kings.

The king called himself yu yi ren (I, the one man) and was titled wang (which is still the word for “king” in Chinese).

He claimed to make military victories and good harvests possible through his prayers.

He divined about topics such as issuing orders, joining allies in military campaigns, and mobilizing troops.

During the reign of Wu Ding, the Late Shang engaged in a series of mostly victorious campaigns against various non-Shang tribes to the west and northwest.

Under WuDing’s son and heir, Zu Geng, however, the Shang started to suffer military defeats.

The extent of Shang influence had shrunk by the dynasty’s end.

No Shang records ofthe final defeat have been found.

According to later texts, the Zhou ruler, King Wu, swept into Shang territory from the Wei River valley to the west and overthrew Di Xin,the last Shang king, at the Battle of Muye in northern Henan Province in about 1045 BC.

IV SOCIETY

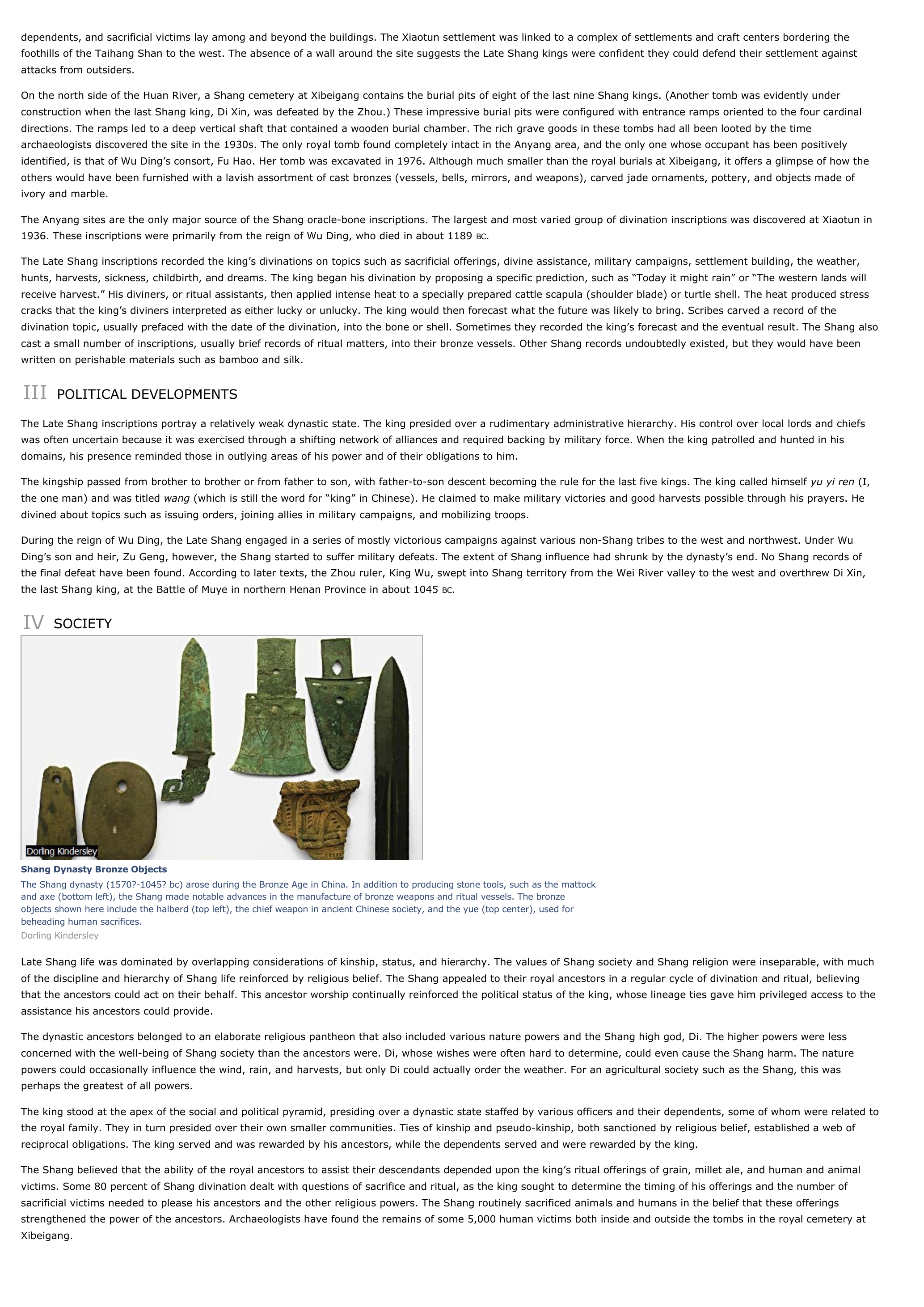

Shang Dynasty Bronze ObjectsThe Shang dynasty (1570?-1045? bc) arose during the Bronze Age in China.

In addition to producing stone tools, such as the mattockand axe (bottom left), the Shang made notable advances in the manufacture of bronze weapons and ritual vessels.

The bronzeobjects shown here include the halberd (top left), the chief weapon in ancient Chinese society, and the yue (top center), used forbeheading human sacrifices.Dorling Kindersley

Late Shang life was dominated by overlapping considerations of kinship, status, and hierarchy.

The values of Shang society and Shang religion were inseparable, with muchof the discipline and hierarchy of Shang life reinforced by religious belief.

The Shang appealed to their royal ancestors in a regular cycle of divination and ritual, believingthat the ancestors could act on their behalf.

This ancestor worship continually reinforced the political status of the king, whose lineage ties gave him privileged access to theassistance his ancestors could provide.

The dynastic ancestors belonged to an elaborate religious pantheon that also included various nature powers and the Shang high god, Di.

The higher powers were lessconcerned with the well-being of Shang society than the ancestors were.

Di, whose wishes were often hard to determine, could even cause the Shang harm.

The naturepowers could occasionally influence the wind, rain, and harvests, but only Di could actually order the weather.

For an agricultural society such as the Shang, this wasperhaps the greatest of all powers.

The king stood at the apex of the social and political pyramid, presiding over a dynastic state staffed by various officers and their dependents, some of whom were related tothe royal family.

They in turn presided over their own smaller communities.

Ties of kinship and pseudo-kinship, both sanctioned by religious belief, established a web ofreciprocal obligations.

The king served and was rewarded by his ancestors, while the dependents served and were rewarded by the king.

The Shang believed that the ability of the royal ancestors to assist their descendants depended upon the king’s ritual offerings of grain, millet ale, and human and animalvictims.

Some 80 percent of Shang divination dealt with questions of sacrifice and ritual, as the king sought to determine the timing of his offerings and the number ofsacrificial victims needed to please his ancestors and the other religious powers.

The Shang routinely sacrificed animals and humans in the belief that these offeringsstrengthened the power of the ancestors.

Archaeologists have found the remains of some 5,000 human victims both inside and outside the tombs in the royal cemetery atXibeigang..

»

↓↓↓ APERÇU DU DOCUMENT ↓↓↓

Liens utiles

- Shang Dynasty - History.

- Qing Dynasty - history.

- Han Dynasty - history.

- Qin Dynasty - history.

- Han Dynasty - history.