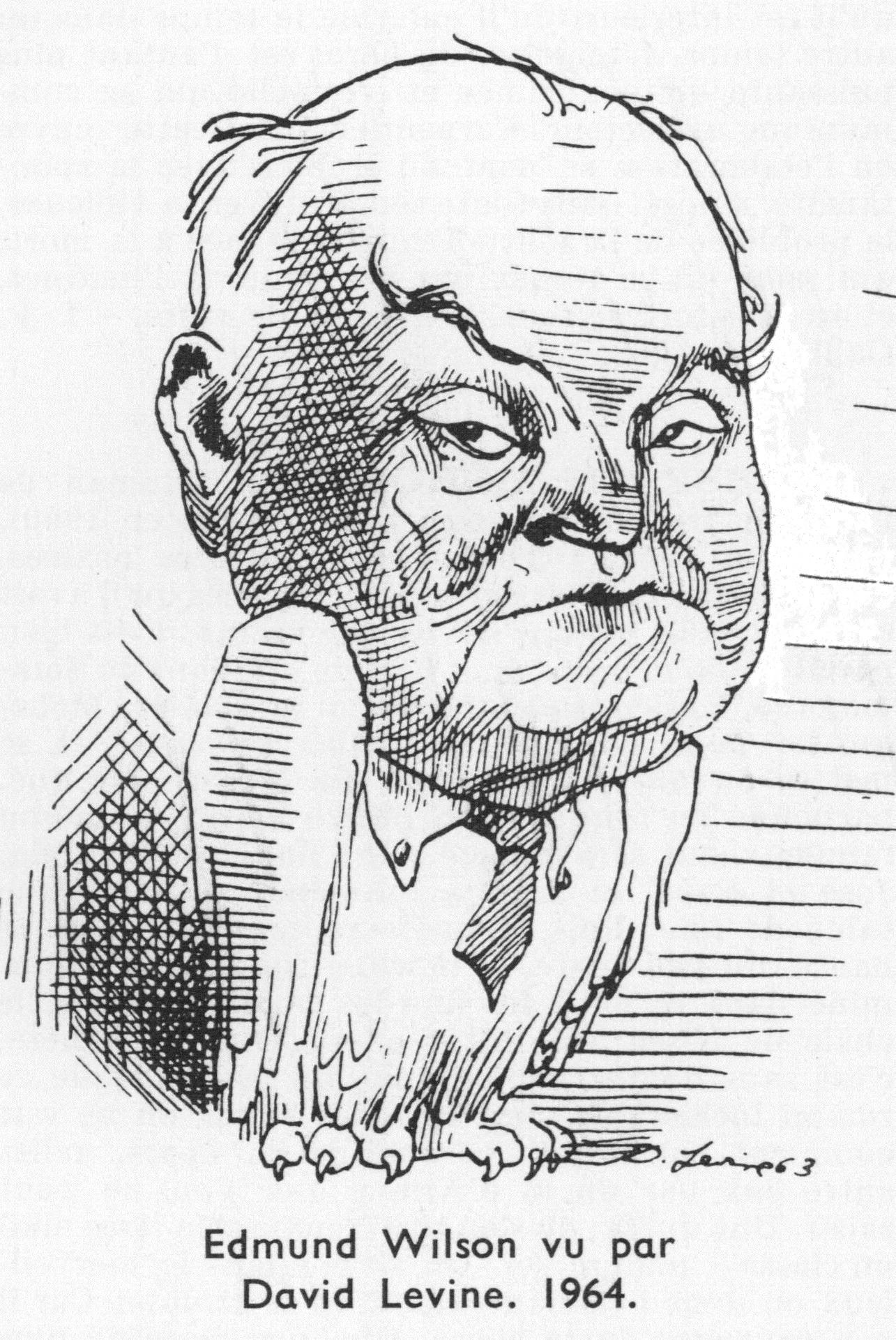

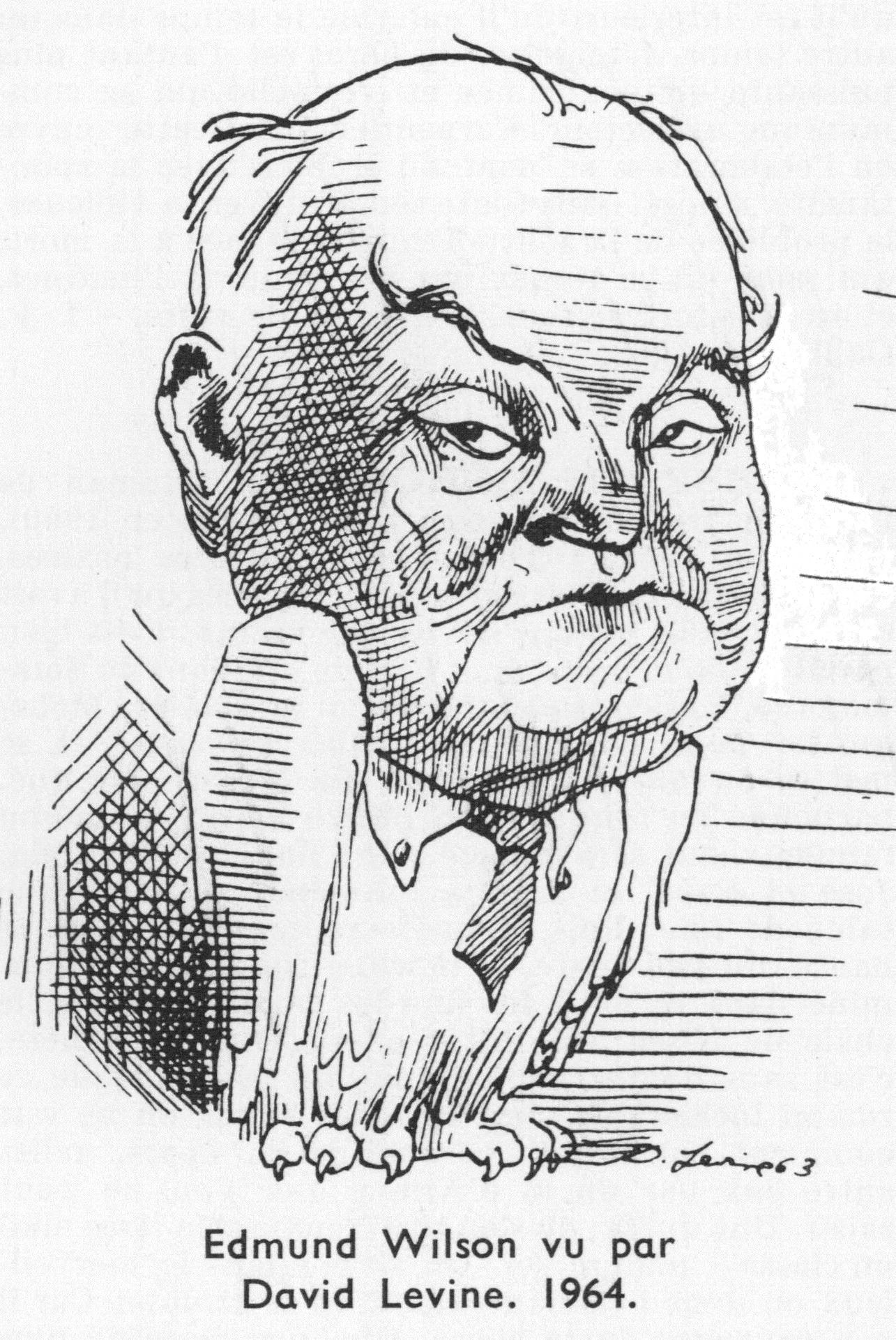

Woodrow Wilson. I INTRODUCTION Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), 28th president of the United States (1913-1921), enacted significant reform legislation and led the United States during World War I (1914-1918). His dream of humanizing "every process of our common life" was shattered in his lifetime by the arrival of the war, but the programs he so earnestly advocated inspired the next generation of political leaders and were reflected in the New Deal of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Wilson's belief in international cooperation through an association of nations led to the creation of the League of Nations and ultimately to the United Nations. For his efforts in this direction, he was awarded the 1919 Nobel Prize for peace. More than any president before him, Wilson was responsible for increasing United States participation in world affairs. A political novice who had held only one public office before becoming president, Wilson possessed considerable political skill. He was a brilliant and effective public speaker, but he found it difficult to work well with other government officials, from whom he tolerated no disagreement. He was, in private, a warm, fun-loving man who energetically pursued his ideals. But the strain of years in office, a tragic illness, and the public's disillusionment following World War I transformed Wilson's image to that of a humorless crusader for a feeble League of Nations. II EARLY LIFE Wilson was born to religious and well-educated people, mainly of Scottish background. His grandparents on both sides emigrated to America in the 19th century and settled in Ohio. Wilson's father, Joseph Ruggles Wilson, studied for the clergy at the Presbyterian-directed College of New Jersey, now Princeton University. He married Janet Woodrow, and early in the 1850s the Wilsons moved to Virginia, where Joseph Wilson taught at Hampden-Sydney College. In 1855 he became the minister of a church in Staunton. His first son and third child, Thomas Woodrow, was born there on December 28, 1856. A Civil War When Woodrow was three years old the family moved to Augusta, Georgia. His early boyhood was happy but somewhat sheltered by the close family ties of the Wilsons. Wilson had a good singing voice and played the violin. When he had a family of his own, he carried on the tradition he had inherited of common prayer and sessions of music and song. The Civil War (1861-1865) was difficult for the Wilsons. Dr. Wilson was an ardent Confederate sympathizer, and young Wilson witnessed the ruthless behavior of federal troops who, under General William T. Sherman, invaded Georgia and South Carolina. Wilson believed all his life that the South had "absolutely nothing to apologize for," so far as its secession from the Union was concerned. He believed further that the South's willingness to shed its blood "rather than pursue the weak course of expediency" had preserved its self-respect. Wilson remained a Southerner throughout his life. B Early Education Wilson was educated partly at home and partly at private schools in Augusta and, after 1870, in war-ravaged Columbia, South Carolina, to which the Wilsons moved. In 1874 they moved again, to Wilmington, North Carolina. Like his father, young Wilson had great admiration for English letters and history. Also like his father, he held William Gladstone, the British Liberal prime minister, to be the greatest 19th-century statesman. The young Wilson took a moral and religious attitude toward society. His critical view of post-Civil War society as materialistic and ungracious agreed with that of such Southern poets as Henry Timrod and Sidney Lanier. C College Years In 1873, Wilson attended Davidson College, a small Presbyterian school in North Carolina, of which his father was a trustee. At that time there was some expectation that he might be preparing for the clergy, but the following year he enrolled at the College of New Jersey, a school favored by young Southern gentlemen. Wilson worked less hard at achieving high grades than at deciding upon a career. He was seriously interested in English literature and read established authors. Politics also interested him, and he studied such classic British orators as Edmund Burke and the techniques of public speech. A leader among the school debaters Wilson, who believed in free trade, refused to defend the case for the government protection of domestic industry even as an exercise in argument. His dream of entering national politics was revealed in his visiting cards, which was written "Thomas Woodrow Wilson, senator from Virginia." Wilson worked diligently to improve his writing, examining the styles of famous English essayists and severely criticizing his own. During his last year at college he published an essay, "Cabinet Government in the United States," in the International Review (August 1879). The essay revealed Wilson's gift for dramatizing ideas and giving them simple and urgent form. His criticism of the powerful committees that dominated the Congress of the United States was largely a criticism of the Congress that had dictated policy to the defeated Southern states during the Reconstruction period following the Civil War, but Wilson's essay went beyond sectional feelings. He wanted a more democratically run Congress, and he envisioned a government of strong and competent Cabinet members, actively engaged in the passage of legislation, rather than a strong president. D Legal Career Wilson was encouraged by the excellent reception of his essay and decided to become a lawyer and enter politics. As a student in the University of Virginia law school, however, he became inpatient with the fine points of law and only reluctantly mastered them. Although his work was outstanding, he found public speaking and political history more satisfying. Despite intermittent illness, he received his law degree and in 1882 settled in Atlanta, Georgia, where he opened a law practice with Edward I. Renick, another idealistic young Southerner. Neither of the young lawyers was particularly skilled at the business side of the venture. In 1883 Wilson abandoned his law career and entered the graduate school of The Johns Hopkins University to study history. III LITERARY AND ACADEMIC CAREER Although a candidate for a degree in history, Wilson continued to analyze politics. His mentor, Professor Herbert Baxter Adams, permitted him to do so. The result was a book-length expansion of his earlier essay on Congress. Accepted and published early in 1885, it sold well. Influential reviewers found Wilson's critical attitude toward American democracy novel and stimulating. Although not strong in scholarship, Congressional Government earned Wilson the Ph.D. degree and enabled him to pursue a literary and academic career. Wilson had been engaged for several years to Ellen Louise Axson, daughter of a Georgia clergyman, and they were married in June 1885. Cultured and vivacious, Mrs. Wilson proved the perfect mate for her sensitive husband. She gave him unqualified support and helped free his mind from everyday pressures. The couple had three daughters. In 1885 Wilson also accepted a position with the newly opened Bryn Mawr College, a school for women near Philadelphia. Wilson was not particularly patient with women as intellectual associates and did not enjoy his teaching duties. He was, however, able to pursue his writing. A University Professor In 1888 Wilson left Bryn Mawr for a professorship in history and political economy at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. There, in 1889, he published The State, a lengthy textbook analyzing the political nature of society. It further established his reputation, even though many of his admirers found it less of an intellectual adventure than Congressional Government. At Wesleyan, Wilson was a successful lecturer, faculty leader, and football coach. He was popular with the students and the administration and often spoke to off-campus meetings. He was offered the presidency of various institutions, including the universities of Virginia and Illinois, and he was also offered professorships at higher salaries. He bided his time, however, until the College of New Jersey, which became Princeton University in 1896, offered him a professorship. The post suited him completely, and he accepted in 1890. Wilson now began a program of publishing and public appearances, becoming one of the foremost academic personalities of the era. His essays on literary topics as well as on history and political science appeared in many magazines. In his works he deplored what he saw as the merely "scientific" spirit of the age and called for a renewed identity with "the great spirits of the past," arguing that they were still relevant to modern times and conditions. He thus brought to his academic subject matter an excitement that stirred his students and colleagues as well as his outside readers and audiences. An Old Master and Other Political Essays (1893) and Mere Literature and Other Essays (1896) were welcomed by critics and reinforced his reputation. As a historian, Wilson shared the views of American history held by most of his contemporaries. His romantic and uncritical George Washington (1896) presented a warm portrait of his great hero. Even so, Wilson tried to persuade readers of his impartiality and hardheadedness. In Division and Reunion, 1829-1889 (1893), which described the differences between the North and South, he agreed that the slavery system was bad in some respects, but he also insisted that as a labor and social system it had worked well. He called President Abraham Lincoln "one of the most singular and admirable figures in the history of modern times" and attempted to distinguish between what he called the "lawyer's facts" and the "historian's facts." Thus, Wilson concluded, the South had seceded legally, but history had determined secession to be wrong. Wilson seemed to abandon hope for a political career, but he continued to follow political affairs. He had little regard for grassroots movements and lacked sympathy with the farmer and labor agitation then sweeping the West and South and demanding economic reform (see Populism). His calls for dedicated leaders and inspired slogans reflected his aristocratic attitude toward politics, as did his admiration for Grover Cleveland as a fearless and independent president. But Wilson also wanted "some great orator who could go about and make men drunk with this spirit of self-sacrifice, some man whose tongue might every day carry abroad the golden accents of that creative age in which we were born a nation." Still responding to strong public demand for his work, Wilson wrote A History of the American People, published in 1902 in five volumes. Wilson's name became familiar and increasingly respected. B University President When the presidency of the college became vacant in 1902, Wilson was unanimously elected. Two presidents of the United States, Grover Cleveland and Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909), attended his inauguration. As president of Princeton, Wilson tried to end practices he believed harmful to education. The student body maintained a club system and separate dining facilities that were undemocratic. They put aside study for what they deemed gentlemanly accomplishments. The university emphasized lectures rather than student-faculty discussion. Wilson had accepted such procedures while establishing himself on campus, but now he prepared for radical departures. He demanded the raising of admission and achievement standards. Following universities in England, he sought to create communities of students, as opposed to exclusive societies. Students were to live and study together in arrangements of four buildings in a rectangle, or quads. Preceptors, rather than lecturers, were to give students personal attention. In a new set of buildings that Wilson proposed to build, the faculty would eat with students and teach them by example as well as by the book. During his first years as president of Princeton, Wilson enlisted the enthusiasm of his teachers and administrators, and word of his exciting ideas spread. Moreover, he brought to his campus many new young instructors who were eager for innovation and change. Some students and faculty, who preferred the old aristocratic ways and who resented his downgrading of sports and his blunt attacks on student clubs, resisted Wilson. He also displeased alumni, who were fond of their own student days and were generally suspicious of reform. Wilson's quad plan was especially open to criticism because it involved great building expenses and would require wide endorsement by wealthy alumni, who were unwilling to give it. To Wilson's deep chagrin the quad plan failed to win the approval of the university's trustees. Wilson always found it difficult to work with people who opposed him and was not receptive to the suggestions of friends who approved his ideals but trusted in slower or modified processes. His troubles increased when Wilson proposed to build a new graduate school. The business school dean was Andrew F. West, a classics scholar. Wilson wanted to build the new school on campus, but West planned to set it apart from the university. Wilson sometimes took contradictory steps to control the affair, and failed to explain the underlying differences between West and himself. What he saw as a question of privilege versus democracy came to appear as merely a "real estate" matter, in which he looked stubborn and petty. West was triumphant in 1910 when an enormous gift to the university required that West's program be adopted. It was a gift the Princeton trustees were unwilling and Wilson was unable to resist. Such academic battles caused Wilson acute nervous strain and sickness. Disheartened and upset, he vacillated between resigning the presidency and staying at Princeton to prevent the total disruption of his designs. He decided to remain. C Wilson in the Progressive Era Wilson's presidency at Princeton coincided with the first part of the Progressive Era in American history. This period of reform lasted from the last decade of the 19th century into World War I. Reformers, or progressives as they were called, were concerned about abuses of power by government and businesses. They did not all agree with each other, but many advocated at least some government regulation of business practices. They wanted the direct election of U.S. senators (in most states the legislature chose them). Some sought the prohibition of child labor, others the prohibition of alcoholic beverages, and for many the conservation of the nation's natural resources was important. Muckrakers (journalists who wrote articles exposing corruption in both politics and in business) often joined with progressives to publicize child labor, unsanitary industrial conditions, business monopolies, and censorship. Progressives believed that the government could play an important role in making the United States a better place to live, and many looked for leadership to President Theodore Roosevelt. Although some critics thought that the educational reforms Wilson advocated were too extreme, his social and political outlook remained largely conservative. For the most part, Wilson avoided controversies and stressed such noncontroversial ideals as the need for a vital church, the spirit of learning, and other inspirational topics. Wilson was specific only on the issue of tariffs, or import taxes, which he viewed as restricting freedom. He called the Republican Payne-Aldrich Bill of 1909, which protected domestic industry by keeping import taxes high, "The Tariff Make-Believe." The task of the country, as he saw it, was to rid itself of special privilege, and "the place to begin is the tariff." Although Wilson was dissatisfied with the politics of the period, he did develop some new attitudes. President Roosevelt was possessed, he thought, with a frenzy to regulate industry. What the country needed instead, he asserted in 1904, was not radical experiment, but a return to reform that gave due regard to law and traditional institutions. Roosevelt's activities did, however, inspire Wilson to abandon his earlier attitudes about the presidency. In lectures published in 1907 in Constitutional Government in the United States he stated that the president could be a "national voice in affairs." The president should not force views on the people but should interpret their wants. Wilson trusted the moral judgment of the country and thought it needed nothing more than a channel for self-expression. IV ENTRY INTO POLITICS Colonel George B. Harvey, editor of Harper's Weekly, was instrumental in shifting Wilson's interests from the academic life to politics. Colonel Harvey was a conservative, an enemy of the progressive elements in the Democratic Party. Wilson's personality and his views as president of Princeton had impressed Harvey, and in 1906 he suggested to other party members that Wilson would make a good Democratic presidential candidate. The idea reawakened Wilson's political ambitions. A Governor of New Jersey New Jersey offered an exciting opportunity to a Democratic candidate because the voters had become disenchanted with the rule of the Republican Party, which was dominated by political machines, organizations that build party loyalty by rewarding loyal party workers with government jobs. Party loyalty was often more important than doing the work. Harvey urged the state Democratic leader, James Smith, Jr., to campaign for Wilson's nomination for the governorship. Smith was won over to the idea of a scholarly and respectable candidate who was without experience in politics and whom, Smith felt, he could control. Wilson took the situation in stride. As he wrote a friend on June 27, 1910: "It is immediately, as you know, the question of my nomination for the governorship of New Jersey; but that is the mere preliminary of a plan to nominate me in 1912 for the presidency." Wilson proved able to change his political attitudes. Once suspicious of workers, he was now ready to appreciate their problems. He also reversed himself on the issue of making the choice of U.S. senators subject to popular vote. Previously, he had wanted state legislatures to continue electing U.S. senators. Wilson had assured Smith that he would not try to build up his own political power in opposition to the regular Democratic organization and with this understanding the party leaders agreed to his candidacy in September 1910. As Wilson continued to study political trends in New Jersey and in the nation, however, he became especially impressed by the strength and quality of the independent Democrats and the progressive Republicans in the state. He realized that they viewed him with suspicion as a possible figurehead for the old-line political managers. On October 20 Wilson resigned the presidency of Princeton, and five days later he sent the progressive George L. Record a letter in which he dramatically separated himself from the politicians who had nominated him. Record was the leader of a group of Progressives that included Joseph Tumulty, later Wilson's private secretary, and Williams McCombs, who was to lead Wilson's drive for the presidency. In his letter, Wilson stated unequivocally that he was opposed to existing machine politics. He asserted that if elected "I shall understand that I am chosen leader of my party and the direct representative of the whole people in the conduct of the government." It was the boldest stand Wilson ever took; he had no organization or political experience and had no way of estimating the effect of his decision on the impending election or on his effectiveness if elected. The progressive tide of that era, however, was in Wilson's favor. He was enthusiastically received by many audiences. Voters did not appear to resent Wilson's aristocratic manners, and they responded well to his speeches, which combined amusing stories with a call to action. In November, he won a sweeping victory, even in areas that normally voted Republican. B Reform Leader The question of who led the New Jersey Democrats, however, remained unsettled. An issue that the election had not resolved made a showdown necessary. "Boss" Smith had been a member of the U.S. Senate and wished to return to it. As one of the architects of Wilson's triumph he felt every right to the office, especially since Wilson had said nothing to indicate he would oppose this ambition. Wilson knew that it would outrage his progressive allies to endorse Smith, and the result was a bitter fight for leadership. Smith tried to rally the support of the legislature; Wilson did the same, but also appealed to the public for help in his fight. This campaign completed Wilson's break with the machine. Smith's accusations of dishonesty and ingratitude failed to impress the people, and Wilson finally won the support of the legislature. Wilson had been educated by his progressive associates and encouraged by the trend toward the Democratic Party throughout the country. He arrived at the statehouse in Trenton with a program fully prepared. Under Wilson's leadership, New Jersey was rapidly transformed from a conservative state into one of the most progressive in the nation. A direct primary law democratized elections, a public utilities commission was created to regulate power and water companies, and a corrupt practices act further curbed the power of the utilities and other giant corporations within the state. Wilson's confidence in his own powers and in his ability to get people to respond to them was at its height. His name became increasingly well-known throughout the country. C Preparations for Presidency Wilson worked to consolidate his control of the Democratic Party in New Jersey and to break ground for the coming presidential struggle. The time seemed propitious. In 1908 Nebraska editor and former U.S. Representative William Jennings Bryan had made his third unsuccessful run for the presidency as the Democratic nominee. The Democrats were looking for a different candidate for the 1912 election. Bryan was, however, certain to have a role in the selection of this candidate. In the Republican Party the break between President William Howard Taft (1909-1913) and his onetime sponsor, Theodore Roosevelt, made a Democratic victory almost certain. Wilson suffered political defeats in 1911 as the Republicans made gains in the New Jersey legislature. Moreover, his own drive for reform weakened, partly because many voters and politicians believed his reforms had come too fast, and partly because Smith and other important politicians opposed Wilson. Wilson's interest in New Jersey politics faded as his attention shifted to national affairs, and he often left the state on speaking engagements intended to make him better known throughout the country. In order to win broad support from other states, he moderated his demands for reform and distanced himself from his progressive associates. Wilson also reassessed his relationship to Colonel Harvey, who continued to line up support for him. In November 1911 he printed a "For President: Woodrow Wilson" banner on the editorial page of Harper's Weekly. He also enlisted for Wilson's candidacy a number of wealthy financiers and other influential people. However, Wilson believed that such backing might taint the progressive image on which he still depended. Wilson alienated Harvey when he told Harvey that his support was hurting Wilson's chances for the presidency. Harvey's subsequent efforts to hurt Wilson probably helped him because they separated him publicly from a man identified with conservative financial interests. A more crucial issue in Wilson's campaign for the presidential nomination was a letter Wilson had written back in 1907 in which he attacked Bryan's leadership of the Democratic Party and wished that "we could do something at once dignified and effective to knock Mr. Bryan once for all into a cocked hat!" This letter, made public in January 1912, threatened to end Wilson's candidacy. His desperate advisors could only hope Bryan would be generous, and fortunately Bryan told the press that he would not encourage a rift between Democratic progressives. A dinner at which Bryan and Wilson were present gave Wilson a chance to put the letter behind him. His praise of "the character and the devotion and the preachings" of Bryan appeased Bryan and satisfied the Democratic Party. Nevertheless, Wilson continued to receive abuse from editors, labor officials, politicians, minority groups, and others who were suspicious of his Southern background and his views on labor. He also began to acquire a group of brilliant and influential followers, who saw him as a farsighted idealist and an able executive. Most important of the followers was Colonel Edward M. House, a wealthy Texan who shunned publicity but was a highly respected figure in Democratic politics. Wilson was impressed by House's ideas, especially those expressed in his novel Phillip Dru: Administrator, published anonymously in 1912. Wilson and House soon became close allies. D The 1912 Convention The numerous aspirants for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1912 included Champ Clark of Missouri and Oscar W. Underwood of Alabama, both outstanding members of the U.S. House of Representatives. Clark came with so many preconvention pledges that nothing could prevent his nomination except the rule that required a two-thirds majority. William F. McCombs, Wilson's manager, came with fewer pledges, but he had raised wide interest in Wilson's cause. Neither congressman could obtain two-thirds of the ballots. Clark could not persuade Underwood to withdraw, and progressives were dissatisfied with Clark's stance on reform and refused to join his candidacy. Through 45 ballots, Wilson's voting strength grew. Bryan, House, and others helped in building his vote, and on the 46th ballot he received the nomination. E Election of 1912 At the Republican convention, Roosevelt opposed Taft, who as president had overruled some of the decisions that Roosevelt had made during his presidency, and had replaced some of Roosevelt's earlier appointments. However, Roosevelt was outmaneuvered and led his followers out of the convention and into the newly organized Progressive Party. As the Progressive Party nominee, Roosevelt pressed a crusade for what he called the New Nationalism. The Democrats countered with Wilson's New Freedom, which, they asserted, would free American potential rather than regiment it. Now a practiced campaigner and aided by a more effective campaign manager, William G. McAdoo of New York, Wilson demonstrated his eloquence and winning personality. Much of his program came from Louis D. Brandeis, a bitter foe of industrial and financial monopoly. Wilson promised fair treatment to black voters, assured labor of his sympathy, and tried to overcome the derogatory statements about immigrants in his books. In addition, his spontaneous manner, friendly joking, and unembarrassed love of country and family reassured voters normally distrustful of intellectuals. Wilson won only 41.85 percent of the popular vote but polled 435 electoral votes, compared with Roosevelt's 88 and Taft's 8. The Democrats also controlled both houses of Congress. V A PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES Domestic Affairs As president, Wilson retained some of his old associates and abandoned others. Bryan was appointed secretary of state from political necessity, rather than preference. McAdoo, as secretary of the treasury, became a close associate of Wilson and later his son-in-law. Josephus Daniels, a North Carolina editor, was named secretary of the navy, and future U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933-1945) was appointed assistant secretary of the navy. Tumulty became Wilson's personal secretary. Colonel House was content to develop a private role as an adviser to Wilson without an official position. Walter Hines Page, another of the many Southerners in Wilson's entourage, an old acquaintance and a noted editor, was made ambassador to Britain. McCombs, however, who believed he had done most to elect Wilson, received no office and retired into obscurity. There had been almost continuous bustle and excitement during the administrations of Theodore Roosevelt and William Taft. The government had strengthened the Sherman Antitrust Act, the federal law that allowed the government to oversee the operations of huge combinations of businesses (called trusts), and it had enacted many other governmental and economic reforms as well. Even so, the incoming Wilson administration promised unprecedented achievement, and Wilson himself set the keynote in his inaugural address. He not only demanded certain legislation but warned the public about lobbyists who were working behind the scenes in Congress to defeat his program. A1 Tariff Reform At the top of Wilson's legislative list was lowering the tariff rates, intended to free American consumers from artificially protected monopolies. Although it involved enormous quantities of information about numerous complex businesses, Wilson pressed relentlessly for quick action. As a result, the Underwood Tariff, drastically slashing taxes on imported goods, was ready for his signature in October 1913. It was the first downward revision of the tariff since before the Civil War (see Tariffs, United States). The bill also included a graduated income tax, permitted by the new 16th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. A2 Federal Reserve System Wilson and his advisers believed that a federal agency was needed to help manage the country's banks. The Pujo Committee, named after Representative Arsène Pujo of Louisiana, which had investigated the "money trust," had increased public awareness of this problem. Wilson also thought a federal agency would make credit easier to get, thus stimulating business. Wilson's position was resisted by bankers who feared too much supervision and by labor leaders who suspected that such a system would give conservative business leaders even more power than they already had. Nevertheless, McAdoo and Carter Glass, a congressman from Virginia, engineered the passage of a bill creating the Federal Reserve System in 1914. The system served as the bank for both the banking community and the government, and has a major role in supervising and regulating banks to help stabilize the national banking system. A3 Other Legislative Achievements Wilson continued to lead the battle for reforms. He established the Federal Trade Commission in 1914 to ensure that one company or group of companies did not gain control of an entire industry (called a monopoly) and force prices up artificially. The commission was empowered to issue cease-and-desist orders once these illegal activities had been proved. Because the Sherman Antitrust Act had been used against labor, the administration sponsored the Clayton Antitrust Act that same year to strengthen its antitrust provisions against monopoly and to limit its use against labor unions. The Clayton Antitrust Act declared illegal such practices as price-cutting to freeze out competitors and other forms of price discrimination. The law also forbade corporate activities that decreased competition and affirmed the right of unions to strike, boycott, and picket. Other New Freedom legislation passed during Wilson's first term included an act improving working conditions for American sailors; the Federal Farm Loan Act, which provided credit for farmers; the Warehouse Act, which helped farmers obtain loans; the Adamson Act, which set an eight-hour workday on interstate railroads; an unemployment compensation act for federal employees; a bill providing greater self-government for the Philippines; and a bill prohibiting child labor. These laws were all passed in 1916, but the child labor act was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1918. A4 Limitations to the New Freedom Many observers at the time were awed by Wilson's political leadership. Circumstances of the time, however, greatly limited the effect of Wilson's program. The major economic reforms were accomplished in 1913 and 1914, years that saw an unexpected industrial decline. This minor depression did not start to recede until after World War I had begun in Europe and production for foreign markets expanded, but then the war disrupted foreign trade, diminishing any benefits from the Underwood Tariff. After the war a high protective tariff replaced it, and the Clayton Act, as interpreted by the courts, was of little help to labor unions. Wilson proved to be less decisive on other reform issues. He had little faith in the ability of women to vote and participate in politics (called suffrage), but for political reasons he was slow to disagree with the determined suffragettes who sought his support for voting rights for women. Similarly, he fought for the child labor law with obvious reluctance and advocated the Adamson Act only to ward off a threatened strike by railroad workers. The most conspicuous failure of the New Freedom was its policy toward blacks. Segregation, the practice of keeping people of different races separate from each other, had never been the practice in federal government offices in Washington, D.C. Faced with strong pressure from fellow Southerners, however, Wilson allowed segregation in the capital. Confronted with his vague promises before election that he would treat blacks with fairness, he could only say that the new policy of segregation was in the best interests of blacks and would angrily terminate the interview when his claims were disputed. B Foreign Relations B1 Latin America Wilson and Secretary of State Bryan sincerely desired good international relations. In the Caribbean and in Central America, they wanted to substitute moral diplomacy for the Dollar Diplomacy of the Taft administration, under which the U.S. government provided diplomatic support to U.S. companies doing business in other countries. Wilson and Bryan demonstrated their desire to improve relations when they agreed to pay Colombia $20 million in reparation for the role the United States had played in the secession of Panama from Colombia. Ex-President Roosevelt, who had encouraged the Panamanian secession from Colombia, took this move as a personal affront and as a sign of weakness. He denied that his foreign diplomacy required apology of any sort. However unwise or improper the Colombian agreement, it demonstrated that Wilson and his Department of State hoped for cordial relations within the hemisphere. Nevertheless, Wilson and Bryan forced conditions on Nicaraguans that infringed upon their sovereignty. They feared that those areas of Nicaragua favorable to the building of a new canal across the isthmus might fall into the hands of some European power. Despite repeated protests of goodwill and regard for the interests of other peoples, the treaty Wilson and Bryan drew up in 1913 restrained the free action of the penniless Nicaraguan regime and permitted American intervention. This was a direct continuation of Taft's diplomacy, which had received the support of Republicans and the sharp criticism of anti-imperialists. In addition, Bryan later authorized the use of troops in the Dominican Republic and in Haiti, even though he was a longtime advocate and architect of plans and treaties furthering peace. B2 Mexican Revolution Wilson had other international problems, particularly in Mexico. Mexico had seen a series of revolutions since 1910. Americans with mining and other interests in Mexico wanted immediate U.S. intervention to protect their property. Wilson decided to adopt a policy of "watchful waiting" and to encourage the election of a constitutional government in Mexico. He refused recognition to General , the choice of American interests in Mexico, because he had illegally seized power. The president put more faith in Huerta's major opponent, Venustiano Carranza. Carranza's forces grew stronger in the provinces due to U.S. support, but Huerta's supporters held power in Mexico City. In April 1914, American sailors of the U.S.S. Dolphin were arrested at Tampico by a Huerta officer. Although the captives were released, the U.S. government was outraged and Wilson had to demand apologies from a government he did not recognize. When news came that a German ship carrying ammunition for Huerta was heading for port, Wilson ordered U.S. troop landings at Veracruz. In the ensuing skirmish more than 300 Mexicans and 90 Americans were killed or wounded, and afterward Mexican public opinion turned against the United States. Wilson gratefully accepted the mediation of Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, but Carranza (who had replaced Huerta) refused to respect their findings. The president then turned his hopes to the peasant leader Francisco "Pancho" Villa, but Villa, harassed by Carranza, attempted to provoke American intervention by crossing the border and raiding towns in the United States. In October 1915, Wilson decided to recognize Carranza as the legitimate heir of the revolution. Villa then seized a number of Americans in January 1916 and executed them. On March 9 he crossed the border into Columbus, New Mexico, where he killed citizens and burned the town. B3 Punitive Expedition Wilson had to respond. Under Brigadier General John J. Pershing a force of more than 6000 troops was dispatched to Mexico. Wilson legitimized the action by acquiring Carranza's permission to pursue Villa. Villa's clever escapes and his second crossing of the border, at Glen Springs, Texas, where he again killed several Americans, inflamed public opinion on both sides of the border and almost caused full-scale war by setting Carranza against the intervention. However, a constitutional government was set up in Mexico in October 1916. Wilson began removing U.S. troops from Mexican soil as the likelihood of U.S. involvement in World War I increased. Wilson's Mexican policy was a failure redeemed only by the fact that he had not tried to force an unpopular government on the Mexican people. C Death of Mrs. Wilson and Remarriage Wilson suffered a severe personal loss on August 6, 1914, with the death of his wife. Combined with the sickness and tension that plagued him, her death was almost more than he could endure. He sought solace in more intensive work and leaned heavily on his few friends. In the following year he met the Southern Edith Bolling Galt, the widow of a Washington jeweler. She and Wilson were married on December 18, 1915. D Approach of War D1 Attempts to Preserve Neutrality World War I began in Europe in 1914. It started as a war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia following the assassination of Archduke Francis Ferdinand, heir to the thrones of Austria and Hungary. The war eventually became a global war involving 32 nations. The Allies and the Associated Powers eventually had 28 nations, including the United Kingdom, France, Russia, Italy, and the United States. They opposed the coalition known as the Central Powers, consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey, and Bulgaria. When the war began, Wilson immediately announced that the United States would be neutral in the struggle, and he urged Americans to be neutral in fact as well as in name. Indeed, there was no other stand possible in a country as divided in its sympathies as the United States at that time. Some 63 peace organizations flourished, including the wealthy Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, attracting many influential educators and editors. Thousands of housewives and workers signed petitions in favor of peace. Moreover, the war seemed too remote from U.S. affairs to affect them significantly. Wilson's sympathies were naturally with the Allies, especially Britain, but he did not want his personal feelings to influence his decisions. The war filled him with genuine horror. The United States had a duty to keep itself "intact," for it "would have to build up the nations ravaged by war." However, his efforts to remain neutral were thwarted by his friends and advisers. His ambassador to the United Kingdom, Walter Hines Page, took pride in his Southern ancestors, admired the British upper classes, and assumed that their cause favored democracy. With British ships in control of the sea lanes, Page defended British policies to Wilson. These policies involved preventing shipments of goods and materials to Germany and demanding them for Britain. Page minimized the rough treatment that British sea captains gave U.S. exporters and insisted that the British were not confiscating the cargoes but were purchasing them. Colonel House influenced Wilson's views on the war. Although he had no office, he was able to bypass the Department of State and to portray U.S. policy to Wilson according to his view of what it should be. Wilson permitted House to travel abroad freely and to discuss issues with high-ranking British and German officials. House was thus able to leave foreign governments with such impressions as he personally preferred. His accounts of these discussions influenced Wilson's thinking and ultimately his decisions. D2 Neutrality Program Anti-German propaganda early in the war cost the Germans any possibility of creating a movement favoring intervention on their side, and German sympathizers mainly argued for peace. Early in the war, House tried to get all warring nations to preserve the freedom of the seas, which would have permitted U.S. ships to travel unhindered. American businesses could thus have fed the United Kingdom and delivered goods to Germany. Such an agreement, however, would have forced Britain to give up its greatest asset, control of the sea, and it was coldly received by the British. Realizing how divided the Americans were, the British encouraged Wilson's neutrality, but they were able also to perceive the value of U.S. mediation, which would involve the United States more intimately in European affairs. The problem lay in determining the conditions of mediation. Germany, with its battle lines in French and Belgian territory, was ready to accept mediation from a position of strength. Therefore Sir Cecil Spring-Rice, the British ambassador to the United States, on behalf of his government rejected House's mediation by stating that "Germany must be punished before peace is made." D3 Sinking of the Lusitania Germany, despite its strong position in the land war, still had somehow to curb the flow of goods to Britain. Since Germany's surface navy had been quickly bottled up, its only weapons were its submarines, called U-boats. On February 4, 1915, the German government announced that British waters would henceforth be considered a war zone, meaning neutral ships in such areas could be attacked by U-boats. Wilson now made the crucial distinction that would thereafter dominate U.S. opinion. He agreed that the Allies had been uncooperative but emphasized that they had not threatened the lives of neutrals. Wilson warned that he would hold the Germans strictly accountable for their actions. It was only a matter of time before Germany's expanded submarine campaign resulted in tragedy. On May 7, 1915, the British liner Lusitania was sunk at sea by a German U-boat. Among the more than 1100 dead were 128 Americans. In the United States there was an outburst of horror and condemnation of Germany. Wilson responded by stressing the need for fair warnings that would preserve lives. However, he would not insist that the British stop carrying war materials on ships that also carried passengers, and he would not restrict the right of Americans to travel. All of this, Secretary of State Bryan believed, could lead to war. On June 8, 1915, he resigned his position and was succeeded by Robert Lansing, who saw the matter as Wilson did. Pacifists, those who opposed war or any type of violence on principle, were dissatisfied with Wilson's unclear policies, but those who embraced the British cause were outraged. Theodore Roosevelt became their most influential voice. He believed Wilson's response to the Lusitania and other sinkings, including that of the Arabic in August 1915 and of the Sussex in March 1916, was completely wrong. He thought Wilson should have armed the country and demanded full satisfaction from Germany under threat of war. D4 Preparedness On June 17, 1915, at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, the League to Enforce Peace was organized with the encouragement of ex-President Taft. Although the organization's long-range goal was peace, Taft himself observed that military strength might be required "to frighten nations into a use of rational and peaceful means." Wilson moved slowly toward preparedness, finally speaking out on January 27, 1916, on the need for a larger army and navy. He emphasized that they would be used for peace. In a later address to the League to Enforce Peace he promised that the United States was willing to join any reasonable association of nations formed in order to defend the right of peoples to govern themselves (self-determination), to be respected as nations, and to be secure against aggressors. He thus announced the American purpose was not limited to the protection of U.S. rights in the current crisis but as including protection of the rights of all nations. D5 Election of 1916 By the summer of 1916 the Democratic Party had lost some of its momentum for reform. Theodore Roosevelt was bringing many of his supporters back into the Republican Party, and Wilson was about to face a more united opposition. At this crucial time a vacancy occurred on the Supreme Court of the United States, and Wilson nominated Louis D. Brandeis to fill it. Brandeis, a progressive, was opposed by many big business interests and was also resented by many people because he was Jewish. There was substantial opposition to his nomination, both because of hatred and because of the fear of what he might do on the court. Wilson courageously defended Brandeis's qualifications. In June the Democrats renominated Wilson. Their platform emphasized peace, and argued that Wilson had kept the United States out of the war. The Republicans nominated Charles Evans Hughes, a former governor of New York with an honored record of reform, and an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Because he seemed to offer common ground to both progressives and conservatives, Hughes appeared to have the political advantage, but he turned out to be an unimpressive campaigner. On election night Hughes appeared to have had won, but as the returns came in from California in the early morning hours, the race went to Wilson, who won the state by a mere 1983 votes. The "Solid South" and a nearly solid West had assured him a narrow victory in the end. VI SECOND TERM AS PRESIDENT A Drift Toward War Wilson saw no contradiction between his domestic and foreign programs; his intention was to extend the domestic crusade for democracy to foreign shores. During his rise to prominence, from 1910 to 1916, he had learned from a variety of people whose help he required, and he was encouraged by the mass-circulation magazines that advocated progressive reforms. Now he made more and more of his own decisions and often neglected to remember that his country was divided. In 1914 the New Republic magazine began publication, appealing not to the masses but to the leaders of society. Periodicals such as the New Republic, as well as his private diplomacy, helped Wilson create the approach that soon brought the United States into the war. Developing suggestions that had long circulated at home and abroad, Wilson decided that only a league of nations that would confront potential belligerents with the strength of its united military and moral powers could keep world peace. In December 1916, Wilson played the role of peacemaker with fresh determination, asking the Allies and the Central Powers to announce their terms to end the war. On January 22, 1917, in an address to the Senate, he appealed for a "peace without victory." However, since he believed that Germany had wrongfully invaded neutral Belgium and unjustly used submarines, his dream of an "equality of nations upon which peace must be founded if it is to last" excluded Germany. With Britain in control of most propaganda and all ocean routes to the United States, German leaders concluded that Wilson's neutrality did not help them. On January 31, 1917, Germany announced that its submarines would freely attack shipping opposed to its interests; no American ship would be safe. Germany gambled that a fullscale assault on the western front combined with unrestricted submarine warfare would defeat the Allies before the United States could build a war machine to support them. Wilson severed relations with Germany but expressed the hope that U.S. ships would not be attacked. He also asked Congress to approve a bill to arm American merchant vessels. Alarmed senators, speaking for those who thought the war was not a U.S. affair and fearful of any step that might start war with Germany, fought to stop the bill. An angry Wilson called them "a little group of willful men, representing no opinion but their own, (who) have rendered the great government of the United States helpless and contemptible." B Declaration of War Wilson and a vast segment of the American people still hoped to stay out of the war. Their hopes vanished when the British presented Wilson with the Zimmermann note, a secret message, which British agents had intercepted and decoded, that advised the German minister to Mexico to seek a German-Mexican alliance against the United States. The publication of this note infuriated the American public and convinced them that war with Germany was necessary. The night prior to asking Congress to declare war, Wilson spoke with a trusted journalist, Frank L. Cobb of the New York World. He feared the requirements at home to support a united war effort abroad: "Once lead this people into war, and they'll forget there ever was such a thing as tolerance. To fight you must be brutal and ruthless, and the spirit of ruthless brutality will enter into the very fiber of our national life, infecting Congress, the courts, the policeman on the beat, the man in the street." Conformity, the president thought, would be the only virtue, and nonconformists would have to pay the penalty. He did not believe the Constitution could survive the demands of war, but he could see no alternative. On April 2, 1917, in one of the most famous of American declarations of war, Wilson denounced the German campaign as "a war against all nations" and called for military action "for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own governments, for the rights and liberties of small nations." C War Leader Wilson called not only the military but also progressives to join the crusade. His secretary of war was Newton D. Baker, an outstanding Ohio municipal reformer. George Creel, a progressive journalist, headed the Committee on Public Information, which enlisted progressive writers to explain war aims to the nation. Ray Stannard Baker, an ex-muckraker who had reported to Wilson about British public opinion, continued to be a close adviser. Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor, was enlisted to guide union leaders through the vital process of war production. Although Wilson's appointees generally opposed harsh suppression of dissidents, they found it hard to keep citizens from attacking those not in favor of the war, especially when the president was calling for unbounded patriotism and criticizing the pacifist statements of those who opposed the war. However, pacifists and those opposed to the Allies' cause were merely suppressed, not persuaded. The opposition included German Americans, socialists, and talented young social reformers such as John Reed, Randolph Bourne, and Max Eastman. They traded their earlier social optimism for bitter antagonism toward the war and Wilson's policies. Industrial and military mobilization toward war production went rapidly, guided by such executives as Bernard Baruch and future president Herbert Hoover (19291933). Wilson gave them authority to act, supported them against their critics, and recognized their achievements. The swift conversion from peace to war confirmed Wilson's conviction that Americans as a nation had joined a crusade. His speeches amazed his associates with their intensity. "As leader and spokesman of the enemies of Germany," wrote Ambassador Page, "your speeches are worth an army in France and more, for they keep the proper moral elevation." D The Fourteen Points Wilson's crusade for democracy received a severe shock when the Russian Revolution was superseded in October 1917 by a Communist Party uprising and a new regime headed by Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky. The new regime was opposed to all warring nations and was eager to undermine them. When the new government found copies of secret treaties the Allies had made with the tsar, they immediately published them. The treaties revealed that the Allies had not entered the war for purely idealistic purposes any more than Germany had. Wilson was not disillusioned to learn that the Allies had been plotting the dissolution of the German Empire. He was well aware that Allied leaders were primarily concerned with national self-interest. His belief was that a league of nations could force them to act on behalf of peace and equity whether they wanted to do so or not. To counter a peace plan suggested by the Bolsheviks, Wilson offered his own plan for peace. Addressing Congress on January 8, 1918, Wilson outlined what he called his Fourteen Points. Wilson's program imagined "open covenants of peace, openly arrived at," freedom of the seas, weapons reduction, territorial adjustments between nations, and Wilson's dearest cause, the League of Nations: A general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike. E End of War Wilson's leadership had made him known all over the world. American troops to support the tired Allied lines arrived in June 1917 and helped them withstand the last desperate German assaults. The new German chancellor, Prince Max of Baden, on October 6, 1918, decided that Wilson's Fourteen Points gave his government a way to surrender without admitting defeat. Wilson was at the height of his career. On November 11 an armistice was signed by Wilson and his discontented Allies, who would have preferred total military victory. In less than a year, however, Wilson would lose all direct influence on world events. On October 24, 1918, he appealed to voters to reelect a Democratic Congress so that he could "continue to be your unembarrassed spokesman in affairs at home and abroad." The voters, however, gave narrow control of both the Senate and the House of Representatives to the Republicans, and control of the powerful Senate Foreign Relations Committee passed to some of Wilson's strongest enemies. Nevertheless, Wilson sailed for Europe on December 4, a move that shocked many citizens. Many thought it was inappropriate for a president to leave the United States during his term of office, and in doing so he removed himself from the rapid social and political change at home. In Europe he was given extraordinary receptions and spontaneous demonstrations reminiscent of his election campaign in 1912. The response persuaded him that popular opinion was overwhelmingly in his favor and would overcome any effort to halt the construction of a league of nations. F Fight for the Covenant On January 18, 1919, Wilson addressed the opening session of the peace conference in Paris, urging it to create a permanent agency to ensure justice and peace. By February 14 he was able to define the organization and duties of a league of nations. Despite his triumphs, Wilson was disliked by European notables, many of whom saw him as arrogant and unrealistic. On the next day he set sail for the United States to sign important legislation, but when he returned to Paris he discovered that Allied diplomats had tried to bury the plans for the league. They advocated dividing the spoils of war and returning to prewar diplomacy. By sheer weight of his own prestige, Wilson, who was fighting sickness and exhaustion, turned the conference back to treaty and covenant negotiations. Wilson desperately tried to create fair principles to settle issues from the war, but he found himself caught in a web of trickery and compromise. Only his belief that the league would rectify all errors sustained him. His most obvious mistake was agreeing to punitive taxes upon the ruined German economy. He had said earlier that he made war not against the German people but its government, but now that government had fallen. Wilson also blundered by failing to include prominent Republicans in his delegation to Paris and while he was away his opponents conspired to defeat his treaty. Popular sympathy favored joining the league, and a majority of the Senate agreed. Senators led by Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts wanted to attach reservations, or conditions, to the treaty creating the league and were called "reservationists." They were joined in opposition to the treaty by the "irreconcilables," senators who were entirely opposed to the treaty because they felt that European affairs were not the business of the United States. The latter group included famous progressive senators William E. Borah of Idaho and Hiram W. Johnson of California. Despite the clever reservations that Lodge attached to the treaty, the Senate seemed sure to pass it. Yet Wilson, although he had accepted numerous compromises from his peers at Paris, was now irreconcilable in his own way. The people, he felt, would force through a sweeping acceptance of the complete treaty. Returning home in July, he was determined to convince them to defend the league. At Columbus, Ohio, on September 4, 1919, Wilson began the first of his detailed explanations of the league's operation. He traveled west, with the passion that in 1912 had brought him to the White House, but in 1912 he had also won over audiences with wit and had courted minority groups. These minority groups were later angered by his war decisions. Now Wilson was discussing and pleading for something that seemed to many of them far removed from their immediate concerns. G Illness and defeat On September 25, on his return from the West Coast, Wilson spoke at Pueblo, Colorado, his last appearance on tour. He suffered a stroke in Kansas and never recovered entirely. On November 19 the Senate rejected the treaty, both the original and the one with Lodge's reservations. Wilson's stroke left him physically incapacitated but his condition was not made public. Returning to peacetime conditions was already difficult, and the lack of a working administrator made more acute the problems of the poor, the needy, the bewildered, as well as those in government charged with running its bureaus. Had Wilson resigned, his vice president, Thomas R. Marshall, would have taken his office, and though he might well have satisfied the "irreconcilables" and brought the United States into the league he lacked the will to seek power for himself. In addition, Mrs. Wilson jealously guarded her husband's prerogatives, and may have feared that the president's resignation might sap his will to live, and to her he was "first my beloved husband whose life I was trying to save ... after that he was the president of the United States." As a result, the president's Cabinet members were denied access to him, as was Colonel House. His wife determined what printed materials he could see, and his state papers became few and unsatisfactory. He held stubbornly to his view of the league and American responsibility to it and to his belief that involvement in European affairs had been justified in every respect. His bitterness toward those who disagreed did not diminish. He refused a pardon to the socialist leader Eugene V. Debs, who had been jailed for publicly opposing the war. The Democratic Party, at its 1920 convention, bestowed lavish praise on Wilson but decided to nominate James M. Cox, a mild proleague advocate and reform governor of Ohio. VII LAST YEARS The league remained Wilson's constant preoccupation. As president he had created no organization to carry on his program and had developed no associates to sustain his cause. After leaving office he retired to a house in Washington, D.C., and for the most part he disappeared from public view. Although he had led the country during the course of the war, the country was now in other hands. Wilson died on February 3, 1924, and was buried in the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.