Temple (building) I INTRODUCTION Wat Phra Kaeo Thailand has nearly 18,000 Buddhist temples, called wats, throughout the country.

Publié le 12/05/2013

Extrait du document

«

colonnaded terraces connected by ramps.

The surrounding area was planted with trees and flowers during Hatshepsut’sreign and for many years after.Gian Berto Vanni/Art Resource, NY

In ancient Egypt, temples were grandiose, built of huge blocks and columns of stone.

Often they were enlarged by successive rulers to form strung-out series of templeparts, as in the gigantic Temple of Amon (circa 1550-1070 BC) at Al Karnak.

The Nile cliffs were used as settings for temples, such as the massive mortuary temple(15th century BC) of Hatshepsut at Dayr al Baḩrī, the superhuman scale of which still inspires awe.

A profusion of sculpture (both in the round and in incised relief) andpainting told of the gods and their special connection with Egypt's rulers.

In the Middle East the hill form called the ziggurat predominated for a long time; this was ahuge stylized constructed mound, sometimes encircled by a walkway.

The best preserved is the ziggurat of Nanna at Ur (about 2100 BC) in present-day Iraq.

Smaller, plainer constructed mounds also appeared.

In the last few centuries BC columned temples with cellas appeared.

IV GREEK TEMPLES

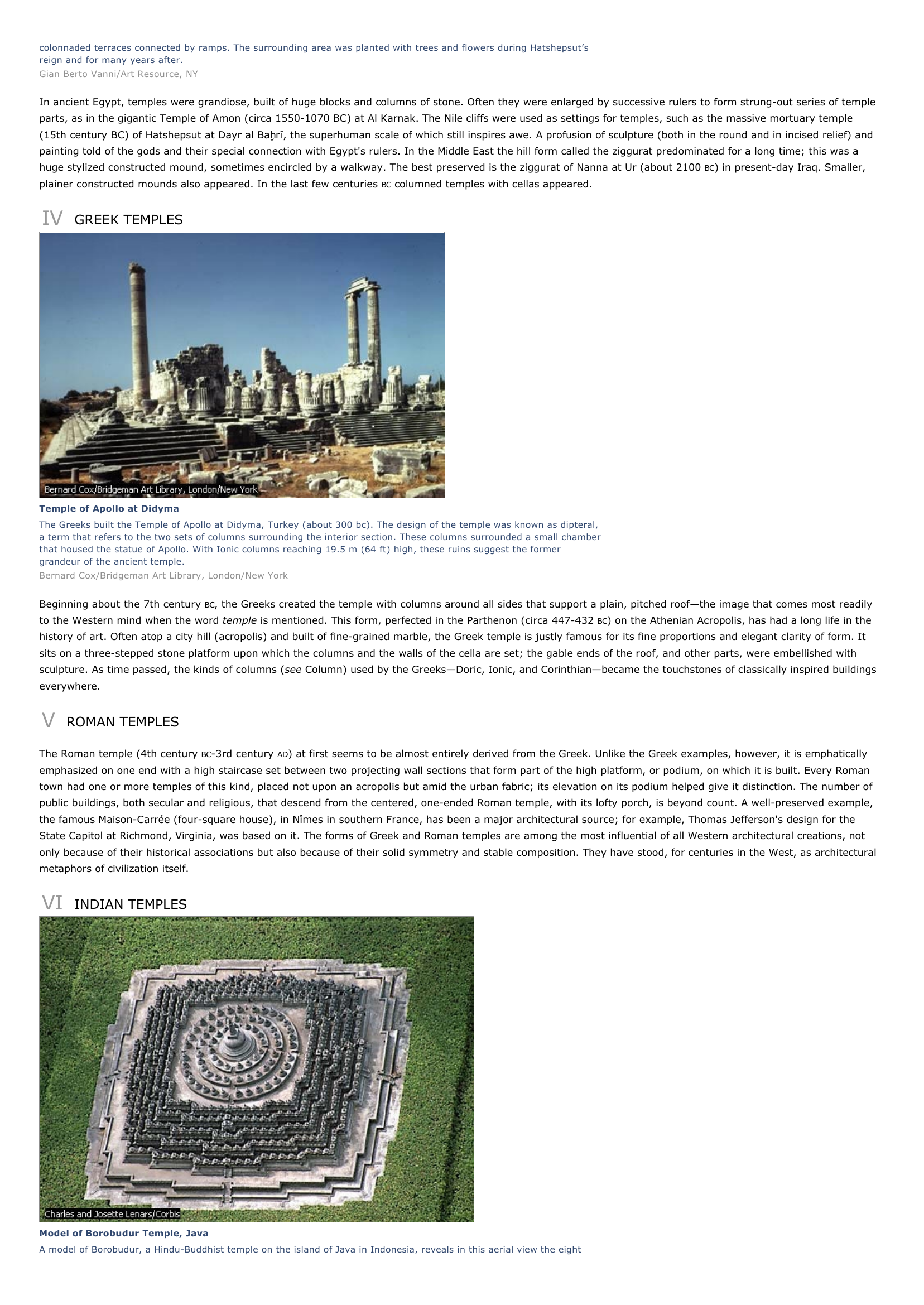

Temple of Apollo at DidymaThe Greeks built the Temple of Apollo at Didyma, Turkey (about 300 bc).

The design of the temple was known as dipteral,a term that refers to the two sets of columns surrounding the interior section.

These columns surrounded a small chamberthat housed the statue of Apollo.

With Ionic columns reaching 19.5 m (64 ft) high, these ruins suggest the formergrandeur of the ancient temple.Bernard Cox/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York

Beginning about the 7th century BC, the Greeks created the temple with columns around all sides that support a plain, pitched roof—the image that comes most readily to the Western mind when the word temple is mentioned.

This form, perfected in the Parthenon (circa 447-432 BC) on the Athenian Acropolis, has had a long life in the history of art.

Often atop a city hill (acropolis) and built of fine-grained marble, the Greek temple is justly famous for its fine proportions and elegant clarity of form.

Itsits on a three-stepped stone platform upon which the columns and the walls of the cella are set; the gable ends of the roof, and other parts, were embellished withsculpture.

As time passed, the kinds of columns ( see Column) used by the Greeks—Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian—became the touchstones of classically inspired buildings everywhere.

V ROMAN TEMPLES

The Roman temple (4th century BC-3rd century AD) at first seems to be almost entirely derived from the Greek.

Unlike the Greek examples, however, it is emphatically emphasized on one end with a high staircase set between two projecting wall sections that form part of the high platform, or podium, on which it is built.

Every Romantown had one or more temples of this kind, placed not upon an acropolis but amid the urban fabric; its elevation on its podium helped give it distinction.

The number ofpublic buildings, both secular and religious, that descend from the centered, one-ended Roman temple, with its lofty porch, is beyond count.

A well-preserved example,the famous Maison-Carrée (four-square house), in Nîmes in southern France, has been a major architectural source; for example, Thomas Jefferson's design for theState Capitol at Richmond, Virginia, was based on it.

The forms of Greek and Roman temples are among the most influential of all Western architectural creations, notonly because of their historical associations but also because of their solid symmetry and stable composition.

They have stood, for centuries in the West, as architecturalmetaphors of civilization itself.

VI INDIAN TEMPLES

Model of Borobudur Temple, JavaA model of Borobudur, a Hindu-Buddhist temple on the island of Java in Indonesia, reveals in this aerial view the eight.

»

↓↓↓ APERÇU DU DOCUMENT ↓↓↓

Liens utiles

- Emily Dickinson I INTRODUCTION Emily Dickinson Heralded as one of the most gifted American writers, Emily Dickinson authored nearly 2,000 poems.

- Westerns I INTRODUCTION Gene Autry Known as the Singing Cowboy, Gene Autry was the star of nearly 100 Westerns during his career as an actor.

- African Music I INTRODUCTION Sacred Christian Music of Nigeria Among the Igede people of Nigeria, Christianity has been syncretized with the existing religious belief system.

- Country Music I INTRODUCTION Willie Nelson Country singer and musician Willie Nelson gained national popularity during the 1970s for a string of country hits, including the 1978 hits "Mammas Don't Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys" and "Georgia On My Mind.

- Greek Mythology I INTRODUCTION Temple of Apollo at Didyma The Greeks built the Temple of Apollo at Didyma, Turkey (about 300 bc).