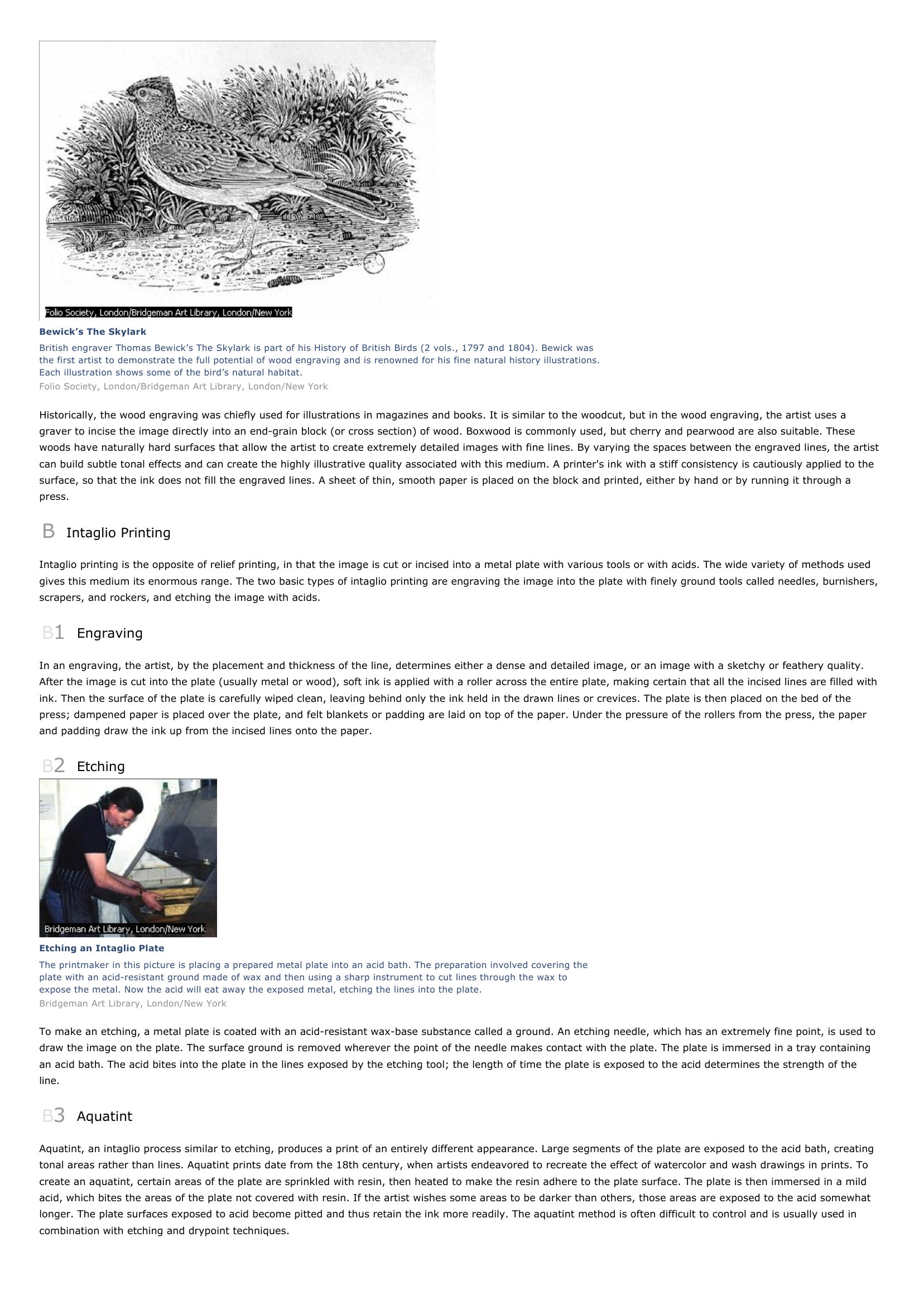

Prints and Printmaking I INTRODUCTION Prints and Printmaking, pictorial images that can be inked onto paper, and the art of creating and reproducing them. The two basic categories of prints are those that are made photomechanically, such as newspaper and magazine illustrations or reproductions of original art sold in museum shops and other stores, and those created by hand for limited reproduction by any of several techniques that require artistic skills and special materials. II TECHNIQUES OF PRINTMAKING The graphic artist can use any of several hand-printing methods: relief, intaglio, planographic, monotype, or stencil. The terms fine print or original print are used to describe the finished work. A Relief Printing In relief printing, the artist carves the image into a block of wood, either as a woodcut or as a wood engraving. A1 Woodcut Pulling a Wood Block Print The printmaker in this picture is "pulling" a wood block print. First he inked the block and then placed it on the press bed. Next he placed a piece of paper over the block and ran everything through the press. Here he shows the image that has been printed onto the paper. In this case, the print was made using more than one wood block and therefore has more than one color. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York This is the oldest method of printmaking. For centuries the basic technique of relief printing has been the cutting away of a portion of the surface of a wood block so that the desired image remains as a printing surface. Traditionally, fruitwoods such as cherry and pear are used; the surfaces of maple and oak are too hard for cutting. In the 20th century, artists have favored softer woods, such as pine. The surface, first smoothed, may be hardened by treating it with a shellac, which makes it more durable under the pressure of a press and facilitates the carving of strong, bold images. The artist may paint or draw the image on the surface; the wood is cut away between the drawn lines, and only the drawn image is left standing on the surface of the block. In essence, this is a relief image. Inking a Wood Block This printmaker is in the process of inking a wood block. He has already created the image on the block by drawing on the surface and then cutting away the wood around the drawing. Now he is using a rubber brayer to evenly distribute a layer of ink on the top surface of the block. Next he will cover the block with paper and run it through a press. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York A roller holding a film of oil-based ink is rolled completely over the block. A sheet of paper--ideally a highly absorbent type such as rice paper--is placed over the block, and the artist may then print the image by hand rubbing the surface with the bowl of a spoon or with any other burnishing instrument. The block and paper may also be run through a press; under the pressure of the press the image is transferred to the paper. The impression is pulled by carefully lifting a corner of the paper and peeling it off the block. Separate blocks are used for color woodcuts, with one block for each color. A2 Wood Engraving Bewick's The Skylark British engraver Thomas Bewick's The Skylark is part of his History of British Birds (2 vols., 1797 and 1804). Bewick was the first artist to demonstrate the full potential of wood engraving and is renowned for his fine natural history illustrations. Each illustration shows some of the bird's natural habitat. Folio Society, London/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Historically, the wood engraving was chiefly used for illustrations in magazines and books. It is similar to the woodcut, but in the wood engraving, the artist uses a graver to incise the image directly into an end-grain block (or cross section) of wood. Boxwood is commonly used, but cherry and pearwood are also suitable. These woods have naturally hard surfaces that allow the artist to create extremely detailed images with fine lines. By varying the spaces between the engraved lines, the artist can build subtle tonal effects and can create the highly illustrative quality associated with this medium. A printer's ink with a stiff consistency is cautiously applied to the surface, so that the ink does not fill the engraved lines. A sheet of thin, smooth paper is placed on the block and printed, either by hand or by running it through a press. B Intaglio Printing Intaglio printing is the opposite of relief printing, in that the image is cut or incised into a metal plate with various tools or with acids. The wide variety of methods used gives this medium its enormous range. The two basic types of intaglio printing are engraving the image into the plate with finely ground tools called needles, burnishers, scrapers, and rockers, and etching the image with acids. B1 Engraving In an engraving, the artist, by the placement and thickness of the line, determines either a dense and detailed image, or an image with a sketchy or feathery quality. After the image is cut into the plate (usually metal or wood), soft ink is applied with a roller across the entire plate, making certain that all the incised lines are filled with ink. Then the surface of the plate is carefully wiped clean, leaving behind only the ink held in the drawn lines or crevices. The plate is then placed on the bed of the press; dampened paper is placed over the plate, and felt blankets or padding are laid on top of the paper. Under the pressure of the rollers from the press, the paper and padding draw the ink up from the incised lines onto the paper. B2 Etching Etching an Intaglio Plate The printmaker in this picture is placing a prepared metal plate into an acid bath. The preparation involved covering the plate with an acid-resistant ground made of wax and then using a sharp instrument to cut lines through the wax to expose the metal. Now the acid will eat away the exposed metal, etching the lines into the plate. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York To make an etching, a metal plate is coated with an acid-resistant wax-base substance called a ground. An etching needle, which has an extremely fine point, is used to draw the image on the plate. The surface ground is removed wherever the point of the needle makes contact with the plate. The plate is immersed in a tray containing an acid bath. The acid bites into the plate in the lines exposed by the etching tool; the length of time the plate is exposed to the acid determines the strength of the line. B3 Aquatint Aquatint, an intaglio process similar to etching, produces a print of an entirely different appearance. Large segments of the plate are exposed to the acid bath, creating tonal areas rather than lines. Aquatint prints date from the 18th century, when artists endeavored to recreate the effect of watercolor and wash drawings in prints. To create an aquatint, certain areas of the plate are sprinkled with resin, then heated to make the resin adhere to the plate surface. The plate is then immersed in a mild acid, which bites the areas of the plate not covered with resin. If the artist wishes some areas to be darker than others, those areas are exposed to the acid somewhat longer. The plate surfaces exposed to acid become pitted and thus retain the ink more readily. The aquatint method is often difficult to control and is usually used in combination with etching and drypoint techniques. B4 Drypoint Drypoint technique is similar to line engraving. A pencil-like tool, usually with a diamond point, is used to draw an image on an untreated copper or zinc plate. Each movement of the tool makes a furrow with a soft metal ridge on either side called a burr, pushed up from the plate by the tool. The artist endeavors to retain the fragile burr throughout printing, because the burr holds the ink and results in a print with rich, velvety lines. The delicacy of the burr and the continuous pressure of the press seldom allow more than 20 to 30 impressions to be printed before the burr is lost. As in the aquatint process, the drypoint print is produced by inking the plate, wiping it clean, placing dampened paper over the plate, and putting the plate through the press. B5 Mezzotint Another technique used in intaglio printing is the mezzotint. The primary tools are various scrapers and the mezzotint rocker, a heavy instrument with a semicircular serrated edge. When the tool is rocked over a copper plate, the edge leaves serrated "teeth" marks. Each movement of the rocker, in effect, leaves the surface covered with burr. In this long and tedious process, the artist completely covers the surface, first working the rocker in one direction, then at right angles to the first direction, then in diagonal directions, and finally once more between the diagonals. If the plate were inked and printed at this stage, the image would be a solid velvety black. The artist creates the image by working a scraper over the surface of the plate, reducing or in some cases completely eliminating the teeth created by the rocker. When the burnishing is complete, the plate is inked and printed. The gradation of tone from solid black areas to pure white gives the mezzotint the striking contrasts for which this medium is best known. C Planographic Printing--Lithography Inking the Lithographic Plate The printmaker in this picture is rolling ink over the surface of the lithographic plate. She is keeping the plate flushed with water so that the ink will only adhere to the spot where she drew the original image. The large rubber roller has been rolled several times on another surface, so that the ink will be evenly distributed when it comes in contact with the plate. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York In planographic printing the image is created directly on the surface of a stone or a metal plate without cutting or incising it. The most common method is called lithography, a process based on the incompatibility of grease and water. Traditionally, the material used for lithography is a special limestone, usually from Bavaria, that is quite heavy and often expensive. Limestone is sensitive to water, particularly in the open areas of the surface left untouched. Zinc or aluminum plates, however, are also often used. Preparing a Lithographic Plate The printmaker in this picture is painting an image on a metal lithographic plate using an oil-based ink. Next she will cover the plate with a mixture of gum arabic and nitric acid, which will cause the surface of the plate that has not been painted to be receptive to water. When the plate is ready to be inked for printing, the surface will be flushed with water as the oilbased ink is rolled onto the plate. This allows only the area that was originally painted to be receptive to the ink. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York The artist first draws the image on a freshly ground surface with a grease crayon or with a pen or brush loaded with thin greasy ink. A mixture of nitric acid and gum arabic is then applied to the entire surface to increase the stone's ability to hold water in a thin film all over. Next, water is poured or wiped over the entire surface; the water is repelled by the grease of the crayon marks but is absorbed elsewhere. When a roller impregnated with greasy ink is passed over the surface, the ink adheres to the greasy drawn areas but is rejected by the wet part of the surface. After the stone is placed on a press and paper is applied, the pressure of the press transfers the image to paper. D Monotype Printing The monotype is a unique print; only one good impression can be pulled from a plate. The artist draws an image with oils or watercolors, or inks, on virtually any smooth surface. Glass is most often used, but a polished copper plate or porcelain can also be employed. The image can be created either by painting it on the surface directly or by the reverse process: first covering the plate completely with an even coat of pigments and then carefully rubbing this away with the fingers or with a brush to form the image. Paper is then applied to the plate and the image is transferred either by rubbing the back of the paper or with the use of an etching press. E Stencil Printing Silkscreen Printing The printmaker in this picture is holding up one end of a large silkscreen frame. The frame is covered with stretched silk. The yellow areas are the places where the silk is exposed; the brownish area around them is where the silk is blocked with a layer of lacquer. The printmaker will now lay the silkscreen down on top of the stretched canvas directly below it. The canvas, painted blue, already has one part of the image silkscreened on it in red. The printmaker will lay some ink in another color at one end of the silk, and using the squeegee in his left hand, he will push a thin layer of ink across the silk. The ink will then print through the exposed areas onto the canvas. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Although the stencil process was used in ancient Rome, its greatest popularity began in the United States during the 1960s, when many artists expressed themselves with blocks of pure color and hard-edged imagery. A stencil is a cutout with open and closed areas. The easiest way to create a stencil is to cut the desired image into paper; the design appears as an open space with solid areas around it. The completed stencil is then placed over a piece of paper, and paint is brushed over the surface. Only the cutout portion will allow the paint to pass through and reproduce the image below. In producing a silk screen--also called serigraph or screenprint--a piece of silk or another porous material is stretched tightly across a wooden frame. In the most direct method, the artist produces the image by creating a design on the fabric with a blocking agent--a stencil, glue, or a combination of glue and a solvent. Paper is placed beneath the screen. Ink is pushed across the entire surface of the screen with a squeegee, and as the squeegee passes over the exposed areas (where there is no blocking agent), the ink is deposited below and the design is transferred to the paper. Artists can also use stencil film or photographic techniques to create the image. III PRINT AND PRINTMAKING TERMS Printmakers, print dealers, and print collectors use six terms that are necessary for the comprehension of prints. A Edition The group of images printed from the plate, stone, block, or the like is called an edition. These identical images are pulled either by the artist or, under the artist's supervision, by the printer. Each sequential print from the body of the edition is numbered--as, for example, 1/100 through 100/100--directly on the print, usually in pencil. Additional proofs, such as artist's proofs, are also part of the edition. B Numbering Numbering indicates the size of the edition and the number of each particular print. Therefore, 25/75 means that the print is the 25th impression from an edition of 75. C Artist's Proofs Artist's proofs are those impressions from an edition (see above) that are specifically intended for the artist's own use. These impressions are in addition to the numbered edition and are so noted in pencil as artist proof or A/P. D Restrike A subsequent printing from an original plate, stone, or block is called a restrike. Restrikes are usually printed posthumously or without the artist's authorization. E States Once the artist has drawn an image, he or she may pull several prints. If the artist subsequently changes the image, the prints made before the change are called first state, and the subsequent prints made after the change, second state. The artist can continue to make changes, with the number of states going as high as ten or more. F Catalogue Raisonné A scholarly reference text in which each print known to have been executed by a particular artist is completely documented and described is a catalogue raisonné. The information given may include title, alternate titles, date, medium, size of the edition, image size, paper used, and other pertinent facts. The term is also used for similar catalogs of paintings, sculptures, drawings, watercolors, or other works by a single artist or workshop. IV HISTORY OF PRINTMAKING Printmaking originated in China after paper was invented (about AD105). Relief printing first flourished in Europe in the 15th century, when the process of papermaking was imported from the East. Since that time, relief printing has been augmented by the various techniques described earlier, and printmaking has continued to be practiced as one of the fine arts. A Chinese Stone Rubbings and Woodcuts Frontispiece to the Jingangjing (Diamond Sutra) The Chinese translation of the Jingangjing (Diamond Sutra), a Buddhist text, was first printed from carved wood blocks in ad 868. This frontispiece to the book shows the combination of illustration and text; the illustrations were done by anonymous artists. The Jingangjing is the earliest known printed book. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Stone rubbing actually predates any form of woodcut. To enable Chinese scholars to study their scriptures, the classic texts and accompanying holy images were carved onto huge, flat stone slabs. After the lines were incised, damp paper was pressed and molded on the surface, so that the paper was held in the incised lines. Ink was applied, and the paper was then carefully removed. The resulting image appeared as white lines on a black background. In this technique lies the very conception of printing. The development of printing continued with the spread of Buddhism from India to China; images and text were printed on paper from a single block. This method of combining text and image is called block-book printing (see Block Book). The earliest known extant Chinese woodcut with text and image combined is a famous Buddhist scroll, about 5 m (about 17 ft) long, of the Jingangjing (Diamond Sutra; AD 868, British Museum, London). These early devotional prints were reproduced from drawings by anonymous artisans whose skill varied greatly. The crudeness of the images indicates that they were reproduced without any thought of artistic interpretation, but as was to be true in Europe during the 1400s, such early works of folk art were important in the development of the print. Toward the end of the Ming dynasty in the 1640s, there appeared a text called Painting Manual of the Mustard-Seed Garden. This was actually an encyclopedia of painting, intended for the instruction and inspiration of artists. Many of its beautiful instructive woodcuts were in color as well as in black and white. A reprint edition of the Painting Manual was brought to Japan, and with it came the basic woodcut technique, which Japanese artists gradually developed. B Japanese Prints The history of Japanese prints is inextricably linked with the art history of China and the relief technique invented there. B1 Early Japanese Woodcuts--Ukiyo-E Japanese Ukiyo-e Print This colored woodblock print of the Edo period (1603-1867) was created by a Japanese artist of the Ukiyo-e school. The artists of this school represented scenes of daily life in a style characterized by graceful, flowing lines and precise detail. Over time Ukiyo-e prints became more colorful and highly patterned. Each color required a different woodblock. ARS Planning The style of Japanese graphic art that emerged in the middle of the 18th century is known as the Ukiyo-e, or "pictures of the floating world," school. Early Ukiyo-e prints were black and white. Created for a popular audience, they were the ephemera of the day, akin to postcards. Certain prints were made for home decoration; others often set the style of the day for fashion and behavior. Color printing from multiple blocks was soon introduced. Flat, solid shapes and dramatic color, design, and composition characterize these later Ukiyo-e prints. The popular theater of Japan, kabuki, helped the Ukiyo-e print to flourish; portraits of the most famous actors in dramatic roles were particular favorites. The artist most associated with this period is T?sh?sai Sharaku. His prints are highly melodramatic, emphasizing exaggerated facial lines and beautiful costumes. Another popular Ukiyo-e subject was the genre (everyday life) scene. Harunobu concentrated on the beauty of young women, depicting them with grace and poetic charm. Perhaps the most outstanding artist to concentrate on the female figure was the inventive Utamaro, who created imagery that is often intimate and candid in nature, with a lyrical quality of line, delicate compositional detail, and assured draftsmanship. B2 19th-Century Japanese Prints Hokusai's The Wave Among the thousands of prints made during his prolific career, the Japanese artist Hokusai created a famous series of prints, entitled Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, from about 1826 to 1833. These prints express a range of moods from serenity to intense drama. Included in this series, The Breaking Wave Off Kanagawa, or, more simply, The Wave, portrays a scene in which a large wave dwarfs Mount Fuji, seen in the background, while it threatens to destroy the boats beneath it. Hokusai's work includes some of the finest examples of Japanese landscape printmaking. Giraudon/Art Resource, NY In the 19th century the emphasis shifted from figurative to landscape subjects. The unsurpassed masters of landscape imagery were Hokusai and Hiroshige. An artist who frequently signed his work "The Man Mad About Painting," Hokusai was preoccupied with landscape. His fascination with every aspect of nature led him to detail seasonal changes; his studies of birds, waterfalls, waves, insects, fish, trees, and mountains culminated in a famous 13-volume sketchbook called Hokusai manga (begun 1814). Rain Shower on the Ohashi Bridge Hiroshige's penchant for capturing ordinary scenes in poetic and intimate ways brought him popularity and success as a printmaker and painter in early-19th-century Japan. Hiroshige created prints with subtle colors and often integrated small human figures into his compositions. In Rain Shower on the Ohashi Bridge, the artist focuses on the rainy scenery but also illuminates the plight of the people crossing the wet bridge. Art Resource, NY Hiroshige stressed the quality of line and also achieved extraordinary effects with color against color. The gradation from intense coloration to the merest hint of color, along with a highly stylized form, characterize Hiroshige's astonishing prints. Among his most notable works are several sets of prints depicting travelers on the T?kaid? Highway (1804) and the Sixty-Nine Stations on the Kiso Highway. By 1856 Hokusai prints had been discovered in Paris, and many others soon surfaced. The enthusiasm they stirred created a wave of japonisme that was to last in Paris for the next 40 years and to become a significant influence on modern art. C Gothic Prints With the establishment of paper mills in several areas of Germany, France, and Italy in the 15th century, the first woodcuts were made in the Western world. The earliest Gothic images were crudely cut from blocks of wood, inked, and printed. The first prints were made to be used as playing cards, then a popular means of entertainment; they were sold for pennies and could be produced in large quantity. Because much of Gothic life centered around the church, the clergy used prints for devotional purposes and distributed them among the people. The images consisted mostly of saints and depictions of the life of Christ and of the Virgin Mary; they also illustrated numerous Bible stories. With the development of movable type, block books became popular, and illustrations could be combined with text. Once a good and inexpensive paper was manufactured, the quality of printing improved, and many editions of illustrated books were published. D Renaissance Prints Melencolia I Melencolia I (1514) by the German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer exemplifies the technique of engraving. Dürer intended this print to symbolize the relationships between morality, theology, and intellectual ideas. The figure of Melancholy represents the artist, who has the knowledge and technical skill to create, but is weighed down by the wings of inspiration, which in this case will not fly. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York The most illustrious artist of the Renaissance in northern Europe was Albrecht Dürer. Born in Nürnberg and trained as a goldsmith, he became the first great graphic master. His phenomenal versatility with the graver and woodcut knife, along with his keen observation of nature and his devotion to prints, brought him success and the admiration of his contemporaries. Of particular note are his numerous series of religious prints and such magnificent single prints as Knight, Death, and the Devil (1513). The Dutch engraver Lucas van Leyden, greatly influenced by Dürer and by the classical style of his Italian contemporaries, gently depicted Dutch landscape and interior scenes. They are important as the foundation of the Dutch school of painting in the following century. The Italian graphic master Marcantonio Raimondi created classical images with a distinctive sense of composition, detail, and sensitivity. Engraving in France and Spain during this time was negligible. By the mid-16th century, prints had become very popular. They were used for all manner of illustrations, including topographical survey, and for portraiture. E Baroque Prints The Three Crosses The Three Crosses (1653) is an etching by the baroque painter and printmaker Rembrandt van Rijn. The artist was known as much for his printmaking as his painting. He reworked this etching at least four times; that shown here is an early version. The print measures 37.5x45 cm (15x18 in) and is part of the collection of the British Museum, London. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Baroque artists of the 17th century felt that an image could be more than just the depiction of reality; it could also have a powerful emotional impact. Gesture could become highly characterized, exaggerated even to a point of being grotesque. Seventeenth-century French engraving and etching are most notably represented by the work of two artists from vastly different schools. Robert Nanteuil produced distinguished court portraits, both those he designed himself and those he copied from the paintings of others. These highly popular engravings brought greater attention to the sculptural, molded quality and delicate strokes that could be produced in this medium. Quite different was Jacques Callot, from the province of Lorraine, who was the first major artist to develop the potential of the etching medium. He discovered that various additional bitings of a plate could create perspective in a print, giving the image a foreground, middleground, and background. His experimentation in special grounds made it possible for work of intense detail to be etched into a tiny plate. With this technical proficiency, Callot created extraordinary imagery in a wide variety of subjects. Kings of France and Spain commissioned Callot to document various historical events. From his wartime etchings Callot issued his own bitter and devastating series of prints, Miseries of War (1633). For a time Callot joined a band of Roma (Gypsies), resulting in his Commedia dell' arte (1618) and Gobbi (1622) series of prints. Here he captured the grotesque, often humorous images of dwarfs and beggars in a variety of costumes and poses. Many print connoisseurs consider Callot's views of cities and country fairs to be among his best work. Among these is the print Fair at Impruneta (1620); in this single large-scale image, Callot captured more than 1000 figures. Callot did much for the advancement of the medium, but Rembrandt stands out as the baroque graphic master. Accomplished in rendering a wide range of subjects from portraits and religious scenes to landscapes, Rembrandt produced prints of both power and subtlety, such as Self-Portrait of the Artist Leaning on a Stone Sill (1639). The Dutch school of graphic artists flourished with portraits, landscapes, interior studies, and scenes of daily life. Ferdinand Bol, Adriaen van Ostade, and Anthony Waterloo pictured Dutch life in etchings. Bol made many fine portraits; van Ostade was noted for his depictions of Dutch peasant life; and Waterloo created beautiful landscapes. The Antwerpen workshop of the Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens was very active. From the pages of the master's sketchbooks and drawings, various artists produced a veritable flood of prints. Anthony van Dyck, Rubens's most talented pupil, settled in England in 1632 and worked as the court painter to Charles I. Van Dyck undertook, with artist collaborators, to etch 128 portraits of the most famous men of his day. The Iconography (1634?-1641), as it is called, is marked by spare lines and technical excellence. F 18th-Century European Prints Carceri d'Invenzione Series The series of etchings Carceri d'Invenzione (Imaginary Prisons) was created by the 18th-century artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi in 1745, with a second edition appearing in 1760. Piranesi was fascinated by ancient Roman architecture, and combined that interest with his own vivid imagination to create these images. The dramatic use of perspective and shadows gives these etchings a powerful sense of drama. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York At the turn of the 18th century, Paris was the artistic center of Europe. Such artists as François Boucher and Jean Honoré Fragonard documented court life in drawings and sketches; influential publishers then had these made into engravings, which proved extremely popular. Until the 18th century England had not developed great strength in the graphic arts. Academic paintings of the nobility and aristocracy were popular, and these images were reproduced beautifully through the mezzotint medium. While the portraitist Sir Joshua Reynolds continued to dignify academic tradition, a triumvirate of English satirists headed by William Hogarth worked against this tradition. James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson, and Hogarth used engraving to satirize almost every aspect of 18th-century England. In tone, they ranged from gentle moralizing to savage commentary and occasional bawdiness. During the 18th century the graphic arts once again flourished in Italy, as exemplified in the work of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo; Giovanni Antonio Canal, known as Canaletto; and Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Tiepolo is noted for his delicacy of line and the spacious quality achieved through economy of line and detail. Canaletto's solid draftsmanship, coupled with a lightness of line, enabled him to capture the courtyards, canals, and beautiful architecture of 18th-century Venice. With an architect's background and his expertise with the graver, Piranesi found a channel for interpreting his passion for Roman antiquities. He created several thousand prints, but of particular note is the series Carceri d'Invenzione (1745; 2nd edition 1760). These are large-scale views of imaginary prisons in spectacular architectural detail, combining the eeriness of a dungeon with huge vaulted ceilings, endless staircases, and massive interior bridges. G 19th-Century European Prints Poster for La Diaphane Face Powder Improvements in color printing paved the way for cost-effective production of illustrated advertising posters during the 19th century. French illustrator Jules Chéret revolutionized the look of poster advertisements. Earlier posters were textoriented and only illustrated to highlight the message of the words; Chéret's posters featured prominent illustrations and a minimum of text. His idealized figures emphasized beauty and vitality: The image, not the words, conveyed the message. © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Photo: Historical Picture Archive/Corbis In the 19th century, leading artists produced an extraordinary range of prints. Spain's Francisco de Goya, for example, combined aquatint with etching to produce bluntly truthful visions of the follies of humankind and the heinous acts of war. Goya's highly individualistic style comes across most characteristically in the print series Los Caprichos (The Caprices, 1797-1799), in which he is almost ferocious in his attacks on the clergy and on the government for its wealth, corruption, and hypocrisy. During the French occupation of Spain in the Peninsular War (1808-1814), Goya created his second most famous series of prints, Desastres de la guerra (Disasters of War, 1810), horrifying images of the hideous fate of people caught in war. Daumier on Justice In the series entitled Gens de justice (People of Justice, 1845-1848), French artist and cartoonist Honoré Daumier denounced the corrupt state of the French justice system in his time. This lithograph from the series shows a lawyer fervently arguing his case before a panel of dozing judges. CORBIS-BETTMANN In Paris, lithography provided the inexpensive means to reproduce images on a large scale in the form of prints, periodicals, and book illustrations. Honoré Daumier was the true voice of the middle class; his particular gift was for political satire and social commentary, and the corrupt reign of Charles X was perfect fuel for his powerful wit. Periodicals such as Le Charivari carried his acute, biting observations on government, the legal profession, and the upper classes and their many foibles. The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (1797-1799) is one of a series of etchings by the Spanish painter and printmaker Francisco de Goya. The title of the series is Los Caprichos. The man in this print is believed to be Goya himself, who at that time was feeling a lack of hope in man's ability to rise above misfortune. Index/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York William Blake was apprenticed to an engraver in 1772 and made antiquarian engravings for seven years. Throughout the 1780s, Blake worked as an engraver and also devised ways to print his own poems and illustrations together. He produced several books of mystical verse with his own unique and strange illustrations. His illustrations for the Book of Job (1826) are among his most intriguing works. La Goulue and Her Sister at the Moulin Rouge French postimpressionist artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec created La Goulue and Her Sister at the Moulin Rouge in 1892. La Goulue was a nightclub dancer and the subject of many drawings and lithographs by Toulouse-Lautrec. The influence of Japanese prints on the artist is clear in this piece, with its unusual palette, calligraphic lines, and flattened space. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Prominent among mid-19th century French artists was the melancholic figure of Charles Méryon. More important than Méryon's technical acumen in etching was the manner in which he saw his adored city of Paris, in particular the oldest sections slated for demolition. He portrayed the charm and elegance of these old buildings in a highly dramatic manner. From the 1860s to the end of the century, the Japanese print exerted an enormous influence on the art and artists of the time. According to tradition, the Parisian artist Félix Braquemond received a set of porcelain from Japan and found that the plates had been wrapped with the prints of Hokusai. Braquemond enthusiastically showed the prints to his impressionist artist friends, who were intrigued by their flat, bold, asymmetrical composition. The lithographic scenes by Edgar Degas of women bathing and dressing are reminiscent of the Japanese style. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was perhaps the most striking and original exponent of japonisme. Employing the subtle to brilliant coloration and the cropping of images characteristic of Japanese prints, he designed posters that capture the essence of charm and elegance. Through the influence of the poster artist Jules Chéret, color lithography grew in popularity. The beautiful color lithographs of Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard portray Parisian scenes as well as the intimacies of family life. Along with Chéret's work, that of Théophile Steinlen and Toulouse-Lautrec made posters powerful mediums for advertising. The Czech artist Alphonse Mucha, in his stylish posters, emphasized the sensuous line and the decorative quality that was characteristic of the turn-of-the-century art nouveau movement. The passionate and masterly Norwegian artist Edvard Munch created woodcuts and lithographs marked by powerful, highly personal imagery. His women are often lush and sensuous, while other images, including his men, are fraught with anxieties and inner tension. H 20th-Century European Prints Woodcut by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner German artist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner created this woodcut portrait of his colleague Otto Mueller. Both were members of Die Brücke ("The Bridge"), the partnership of expressionist artists formed in Dresden, Germany, at the beginning of the 20th century. The artists were influenced by primitive art and by the paintings of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. Christie's ImagesCopyright by Dr. Wolfgang & Ingeborg Henze-Ketterer, Wichtrach/Bern The many art movements that have coursed through this century are unusual in their diversity and number, and also in their rapid development. They include fauvism, cubism, expressionism, surrealism, abstract expressionism, op art, pop art, and superrealism; printmakers have played a part in all these movements. At the turn of this century Paris still reigned as the center of Western art and printmaking. A group of postimpressionists exhibited their paintings at the 1905 Salon d'Automne, among them Henri Matisse, Georges Rouault, and André Derain. Critics called them fauves (see Fauvism), literally "wild beasts." These youthful artists sought to use color in a totally unrestrained fashion, which, with the exception of Matisse's graphic works, carried over into their prints. Matisse's most important prints, however, are black-and-white lithographs. In his many odalisques (models posed as harem beauties), Matisse chose a highly decorative background filled with a patterned design, while his model was dressed in an exotic Persian-style costume. This rich, opulent atmosphere suggests, in black and white, the intensity of vivid color. Cubism, which translated the realistic image into abstract form by dissolving it into cubic elements and by crisscrossing shapes and planes, was the joint achievement of the French artist Georges Braque and the Spanish artist Pablo Picasso, who worked together beginning in 1909. Founded on the qualities of superb draftsmanship, Picasso's earliest prints (1904) speak of directness and compassion, and evoke a somber and sentimental nature. In 1930 he was commissioned by the publisher Ambroise Vollard to issue a series of 100 prints, the famous Vollard Suite (published 1937), one of the artist's greatest graphic achievements. The subject matter of these etchings and aquatints ranges from the artist's studio and model to sensuous and emotional depictions of minotaurs, and to portraits of Vollard himself. Other artists who produced important cubist prints were Braque, Jacques Villon, Juan Gris, and Louis Marcoussis. Each worked to achieve a warm and harmonious relationship between the etched line and overall tonal quality. Surrealism, which sought imagery that welled up from the unconscious and from dreams, produced a number of famous printmakers, exemplified in the work of the Spanish artist Joan Miró, whose color lithographs have a delightfully whimsical quality. A similar whimsicality, with bizarre overtones, is found in works by André Masson and Yves Tanguy. In 1910Marc Chagall came to Paris from Russia. Throughout a long career Chagall distinguished himself as a painter and printmaker, combining a folkloric, naive charm with rich, dreamlike imagery. Chagall's major graphic achievements are the series of prints Mein Leben (My Life, 1922), the 100 etchings (1948) for the novel Dead Souls by Russian writer Nikolay Gogol, and the 105 etchings illustrating the Bible (1956). At the turn of the century, German artists developed expressionism--a style emphasizing subjective emotions and responses to the external world--in reaction against French impressionism and postimpressionism. As in the Gothic tradition, the immediacy and boldness of the woodcut made it a perfect medium. One group of Dresdenbased artists, called Die Brücke ("The Bridge"), and included Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Erich Heckel, and Otto Müller. Their styles varied from striking contrasts of sections of roughly gouged wood, in Schmidt-Rottluff's cartoonlike prints and Heckel's harsh portraits, to Mueller's lyrical composition of female figures. See Brücke, Die. In Munich another group, Der Blaue Reiter (German for "The Blue Rider"), emerged, led by the Russian-born Wassily Kandinsky. Together with the Swiss artist Paul Klee, Der Blaue Reiter artists developed a refined abstraction, in which rhythm of line and a dramatic sense of color dominated, with an absence of representational objects. Klee, a unique genius, soon chose to work alone in Switzerland; he used images with seemingly childlike, naive qualities to create highly sophisticated personal statements with universal implications in the guise of fantasy. I Early American Prints In colonial America the decorative arts rather than the graphic arts flourished. There was, however, an interest in portraiture; the first mezzotint in America, dated 1728, is a portrait of the noted clergyman Cotton Mather by Peter Pelham. After the American Revolution (1775-1783), more diversified subject matter developed. Engravings were made to commemorate famous battles, to depict historical events, and to honor generals and noted statesmen. Perhaps the best-known American historical print of this period is Boston Massacre (1770) by silversmith and patriot Paul Revere. Most early American prints were made by professional engravers who almost always relied on paintings for their subject matter. Prints also became important as a vehicle for the spread of political and social ideas. J 19th-Century American Prints American Forest Scene--Maple Sugaring American Forest Scene--Maple Sugaring (1856) is an example of a lithograph by the 19th-century American printers Currier & Ives. This print is probably hand-colored, and it is typical of the Currier & Ives style, which was simple and straightforward. These prints are excellent records of life in the 19th century. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York By the 1800s the first truly American printmaking movement had come into being. Topographical imagery was popular, as were genre scenes of American farm and city life. The most outstanding prints created during the 1820s and 1830s were the remarkable engravings by Robert Havell, Jr., for the folios of American birds (published 1827-1838) painted by American naturalist and artist John James Audubon. Because they were less costly to produce, lithographs soon became more popular than engravings. The first private American concern to sell prints was founded by Nathaniel Currier. He and his partner, James Ives, became "printmakers to the American people" (see Currier & Ives). Winslow Homer began his career as a magazine illustrator for Harper's Weekly. He eventually created two masterful engravings, Eight Bells (1887) and Perils of the Sea (1888), based on two of his best-known canvases. The most important American printmaker of the last half of the 19th century was James Abbott McNeill Whistler. He learned etching technique at the U.S. Coastal Survey in Washington, D.C. In 1855 Whistler went to Europe, where he began creating his famous series of prints, first of Paris (1858) and London (1860), and then Venice (1880, 1881). His experimentation with technique and refinement of compositional details earned Whistler a high position in printmaking. Mary Cassatt, an artist from Philadelphia, went to study in Paris and settled there. An early impressionist, she developed expert technique in drypoint, etching, and aquatint. She further expanded her oeuvre by endeavoring to re-create the quality of the Japanese woodblock print in a series of color aquatints in which areas of soft color are combined with decorative patterning; these rank among her most famous prints. Childe Hassam and Maurice Prendergast were America's important impressionists. Hassam concentrated on etching, using short staccato strokes within a firm design. Prendergast for a short time produced monotypes. His subtle and refined palette was well suited to this spontaneous and demanding method of printmaking. K 20th-Century American Prints The Ashcan School was America's first art movement to break away from European styles. The etchings of John Sloan and Edward Hopper and the lithographs of George Bellows were the first American prints to catch the vitality of urban life in all its aspects, from squalor to grandeur. The Armory Show exhibition of 1913 brought modernism to American printmakers; the repercussions of the show influenced American artists for many years to follow. Brooklyn Bridge Swaying (1913) by American artist John Marin is one of the earliest American prints to break away from traditionalism. In this work, the vibrancy and swerving energy of the etched line and the semidistortion express the artist's moods and the emotions aroused during the work's creation. Lyonel Feininger, through the boldness of the woodcut medium, also created abstract patterns that convey his intense personal involvement. During the depression of the 1930s, evocations of the American scene came into vogue. The Midwest regionalists Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, and Grant Wood epitomized rural America in stylized detail in their prints. Reginald Marsh, Isabel Bishop, and their teacher Kenneth Hayes Miller were the best-known members of the so-called Fourteenth Street School of New York City's Greenwich Village. This street, during the 1930s, was a lively commercial area; its office girls, shoppers, and panhandlers were vividly captured by all three artists in their prints. Miller was an influential teacher at the Art Students League; his students--Marsh, Bishop, Bellows, and others--each developed a highly personal view of New York. Raphael Soyer continued to make prints in the realistic tradition, with many lithographs and etchings of young women--dancers and models. L Recent Trends Two Women In the 1950s Japanese printmaker Munakata Shiko won several international art awards, bringing attention not only to himself, but to modern Japanese prints in general. Two Women is owned by Christie's in London, England. Christie's, London/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York The English artist Stanley William Hayter established and ran, from 1927 to 1940, a Paris workshop called Atelier 17 to teach etching and engraving. Atelier 17 was transferred to New York in 1940 and remained in operation for 15 more years, becoming the mecca for creative intaglio printmaking. The technical innovations that later came from such artists as Mauricio Lasansky, Antonio Frasconi, and Gabor Peterdi were a direct result of Hayter's inspiration. In the 1960s the specialized workshop for the graphic artist became important. The most influential was the studio run by Tatyana Grosman on Long Island, where major artists gathered to make prints. This arrangement was so successful that a close working relationship between master printer and artist developed in several other studios. The Tamarind Lithography Workshop, founded in California by June Wayne and now located in New Mexico, became an important creative center for graphic artists. Many of the best contemporary artists have been drawn to such centers, including Larry Rivers, Josef Albers, and such abstract expressionists (see Abstract Expressionism) as Robert Motherwell, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns. Printmaking workshops are now spread across the country, mostly located at major colleges and universities. Drawing away from the vision of the abstract expressionists were young artists of the pop culture (see Pop Art). Here material from the mass media--magazines, newspapers, films, and photographs--were combined impersonally and repetitively, often resulting in imaginative imagery. Through the use of advertisements and other mundane images, artists such as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Robert Indiana set out to challenge graphic tradition. American artist Jim Dine, who worked in a variety of styles, is another accomplished printmaker of the 20th century. See also Book; Illustration; Lithography; Photography; Printing; Printing Techniques; Xerography. Contributed By: Sylvan Cole Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.