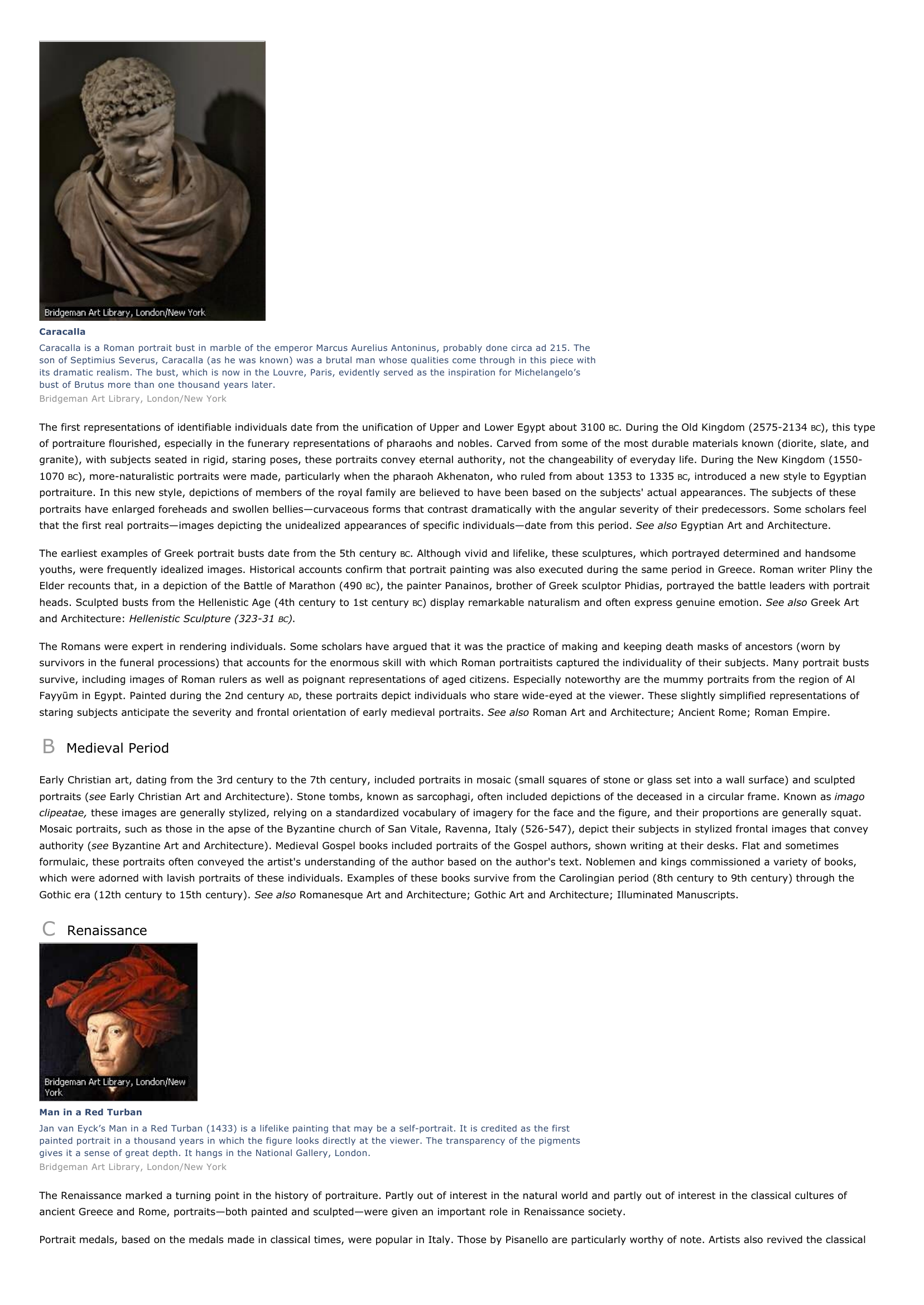

Portraiture I INTRODUCTION Portraiture, visual representation of individual people, distinguished by references to the subject's character, social position, wealth, or profession. In the broadest sense, portraiture can include representations of animals (favored pets or prize-winning livestock, for example) or even representations of dwellings. As discussed here, however, portraiture refers only to images of people. II CHARACTERISTICS OF PORTRAITS Portraitists often strive for exact visual likenesses. However, although the viewer's correct identification of the sitter is of primary importance, exact replication is not always the goal. Artists may intentionally alter the appearance of their subjects by embellishing or refining their images to emphasize or minimize particular qualities (physical, psychological, or social) of the subject. Viewers sometimes praise most highly those images that seem to look very little like the sitter because these images are judged to capture some nonvisual quality of the subject. In non-Western societies portraiture is less likely to emphasize visual likeness than in Western cultures. Portraits can be executed in any medium, including sculpted stone and wood, oil, painted ivory, pastel, encaustic (wax) on wood panel, tempera on parchment, carved cameo, and hammered or poured metal. See also Woodcarving; Oil Painting; Ivory Carving; Crayon; Encaustic Painting; Tempera Painting; Founding; Metalwork. Portraits can include only the head of the subject, or they can depict the shoulders and head, the upper torso, or an entire figure shown either seated or standing. Portraits can show individuals either self-consciously posing in ways that convey a sense of timelessness or captured in the midst of work or daily activity. During some historical periods, portraits were severe and emphasized authority, and during other periods artists worked to communicate spontaneity and the sensation of life. III ASSESSMENT OF PORTRAITS Portraiture is considered a specialized subgroup of art, and therefore it has its own standards and criteria. A portrait is judged, in part, on how closely it resembles the appearance of the subject. Portraits, however, are not limited to simply recreating external appearances and situations and often are highly regarded for portraying a range of qualities of an individual or group. Artists utilize elements of their portraits--backgrounds, props, or mounts for the sitter (thrones or horses, for example)--to provide information about the subject's character or place in society. The most appreciated portraits exhibit strong composition, refined handling of materials, and an appropriate or interesting application of color. See also Sculpture; Painting; Drawing; Prints and Printmaking; Folk Art. IV FUNCTIONS OF PORTRAITURE Portrait of Mrs. Mol Davies In order to be successful, most 17th-century portraitists followed style conventions of the era. Subjects often appeared in classically inspired settings in poses that projected nobility and grandeur. This painting of a wealthy patron of Dutch-born artist Sir Peter Lely displays the rich use of color for which the artist is known. The Trustees of the Weston Park Foundation/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Portraiture has broad and varied functions. In the Roman Empire (44 BC-AD 476), portraits of the emperor were required to be present in order for court proceedings to take place. Many societies regard portraits as important ways to convey status and acknowledge power and wealth. During the Middle Ages (5th century to 15th century) and the Renaissance (14th century to 17th century), portraits of donors were included in works of art as a means of verifying patronage, power, and virtue. Many societies have employed portraits as a means of remembering the dead. Egyptian mummy portraits and Roman death masks played important roles in death rituals. Japanese portrait sculptures commemorate deceased monks, and skulls refashioned to be lifelike are memorial representations of ancestors in Oceania. V PORTRAITURE IN EUROPE AND THE AMERICAS The history of portraiture spans most of the history of Western art, from the art of ancient Egyptian and Greek civilizations to the modern art of Europe and North America. A Ancient Portraiture Caracalla Caracalla is a Roman portrait bust in marble of the emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, probably done circa ad 215. The son of Septimius Severus, Caracalla (as he was known) was a brutal man whose qualities come through in this piece with its dramatic realism. The bust, which is now in the Louvre, Paris, evidently served as the inspiration for Michelangelo's bust of Brutus more than one thousand years later. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York The first representations of identifiable individuals date from the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt about 3100 BC. During the Old Kingdom (2575-2134 BC), this type of portraiture flourished, especially in the funerary representations of pharaohs and nobles. Carved from some of the most durable materials known (diorite, slate, and granite), with subjects seated in rigid, staring poses, these portraits convey eternal authority, not the changeability of everyday life. During the New Kingdom (15501070 BC), more-naturalistic portraits were made, particularly when the pharaoh Akhenaton, who ruled from about 1353 to 1335 BC, introduced a new style to Egyptian portraiture. In this new style, depictions of members of the royal family are believed to have been based on the subjects' actual appearances. The subjects of these portraits have enlarged foreheads and swollen bellies--curvaceous forms that contrast dramatically with the angular severity of their predecessors. Some scholars feel that the first real portraits--images depicting the unidealized appearances of specific individuals--date from this period. See also Egyptian Art and Architecture. The earliest examples of Greek portrait busts date from the 5th century BC. Although vivid and lifelike, these sculptures, which portrayed determined and handsome youths, were frequently idealized images. Historical accounts confirm that portrait painting was also executed during the same period in Greece. Roman writer Pliny the Elder recounts that, in a depiction of the Battle of Marathon (490 BC), the painter Panainos, brother of Greek sculptor Phidias, portrayed the battle leaders with portrait heads. Sculpted busts from the Hellenistic Age (4th century to 1st century and Architecture: Hellenistic Sculpture (323-31 BC) display remarkable naturalism and often express genuine emotion. See also Greek Art BC). The Romans were expert in rendering individuals. Some scholars have argued that it was the practice of making and keeping death masks of ancestors (worn by survivors in the funeral processions) that accounts for the enormous skill with which Roman portraitists captured the individuality of their subjects. Many portrait busts survive, including images of Roman rulers as well as poignant representations of aged citizens. Especially noteworthy are the mummy portraits from the region of Al Fayy? m in Egypt. Painted during the 2nd century AD, these portraits depict individuals who stare wide-eyed at the viewer. These slightly simplified representations of staring subjects anticipate the severity and frontal orientation of early medieval portraits. See also Roman Art and Architecture; Ancient Rome; Roman Empire. B Medieval Period Early Christian art, dating from the 3rd century to the 7th century, included portraits in mosaic (small squares of stone or glass set into a wall surface) and sculpted portraits (see Early Christian Art and Architecture). Stone tombs, known as sarcophagi, often included depictions of the deceased in a circular frame. Known as imago clipeatae, these images are generally stylized, relying on a standardized vocabulary of imagery for the face and the figure, and their proportions are generally squat. Mosaic portraits, such as those in the apse of the Byzantine church of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy (526-547), depict their subjects in stylized frontal images that convey authority (see Byzantine Art and Architecture). Medieval Gospel books included portraits of the Gospel authors, shown writing at their desks. Flat and sometimes formulaic, these portraits often conveyed the artist's understanding of the author based on the author's text. Noblemen and kings commissioned a variety of books, which were adorned with lavish portraits of these individuals. Examples of these books survive from the Carolingian period (8th century to 9th century) through the Gothic era (12th century to 15th century). See also Romanesque Art and Architecture; Gothic Art and Architecture; Illuminated Manuscripts. C Renaissance Man in a Red Turban Jan van Eyck's Man in a Red Turban (1433) is a lifelike painting that may be a self-portrait. It is credited as the first painted portrait in a thousand years in which the figure looks directly at the viewer. The transparency of the pigments gives it a sense of great depth. It hangs in the National Gallery, London. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York The Renaissance marked a turning point in the history of portraiture. Partly out of interest in the natural world and partly out of interest in the classical cultures of ancient Greece and Rome, portraits--both painted and sculpted--were given an important role in Renaissance society. Portrait medals, based on the medals made in classical times, were popular in Italy. Those by Pisanello are particularly worthy of note. Artists also revived the classical practice of making portrait busts, good examples of which are the highly naturalistic busts by Antonio Rosellini and the elegant sculptures of Francesco Laurana. Profile portraits, inspired by ancient medallions, were particularly popular in Italy between 1450 and 1500. Later, profile portraits depicted donors, represented in the paintings and altarpieces they had commissioned. Important portraitists include Sandro Botticelli, Raphael, and Leonardo da Vinci. Perhaps the finest 16th-century portraitist was Venetian artist Titian, who portrayed many leading figures of his day. Italian Mannerist artists contributed many exceptional portraits that emphasized material richness and elegantly complex poses, as in the works of Agnolo Bronzino and Jacopo da Pontormo. One of the best portraitists of 16th-century Italy was Sophonisba Anguissola from Cremona, who infused her individual and group portraits with new levels of complexity. Northern European artists used the profile format far less often, and very seldom after 1420. In the Netherlands, Jan van Eyck was a leading portraitist; The Arnolfini Marriage (1434, National Gallery, London) is a detailed full-length portrait of a couple. Leading German portrait artists include Hans Holbein the Younger and Albrecht Dürer. See also Renaissance Art and Architecture; Mannerism. D Baroque and Rococo Self-Portrait by Rembrandt This self-portrait by the Dutch baroque artist Rembrandt van Rijn was painted in 1669, the last year of his life. It is 86 x 70.5 cm (approximately 34 x 28 in) and hangs in the National Gallery, London. Rembrandt painted a large number of selfportraits throughout his life; the later ones in particular are noted for their psychological depth and the artist's technical skill in the use of chiaroscuro (contrasts of light and shadow). Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York During the baroque and rococo periods (17th century and 18th century, respectively), portraits became even more important. In a society dominated increasingly by secular leaders in powerful courts, images of opulently attired figures were both symbols of temporal power and wealth, and a means to affirm the authority of certain individuals. Flemish painters Sir Anthony van Dyck and Peter Paul Rubens excelled at this type of portraiture. Also during these periods, artists increasingly studied the facial expressions that accompanied different emotions and they emphasized the portrayal of these human feelings in their work. In particular, Italian sculptor Gianlorenzo Bernini and Dutch painter Rembrandt explored the many expressions of the human face. This interest fostered the creation of the first caricatures, credited to the Carracci Academy, run by painters of the Carracci family in the late 16th century in Bologna, Italy (see Carracci, Annibale). Group portraits were produced in greater numbers during the baroque period, particularly in the Netherlands. Dutch painter Frans Hals used dashed lines of vivid color to enliven his group portraits, and Rembrandt experimented with introducing time and historical references into the group portrait, most notably in his famous Night Watch (1642). Bernini's bust Scipione Borghese (1632) captured the subject in mid-conversation and is considered a benchmark of baroque portraiture both because of its lifelike depiction of the subject and because it showed the subject in action. See also Baroque Art and Architecture. Self-Portrait by Kauffmann This self-portrait was painted by the Swiss artist Angelica Kauffmann in the late 18th century. Kauffmann, who was trained in the rococo style under the tutelage of Sir Joshua Reynolds, was a proponent of the neoclassical school of painting. This piece shows the artist in a Roman setting, wearing Roman garments. The painting has elements of the rococo style but also has a stillness and serenity not found in rococo work. Tate Gallery, London/Art Resource, NY Rococo artists, who were particularly interested in rich and intricate ornamentation, excelled at the refined portrait. Their attention to the details of dress and texture increased the efficacy of portraits as testaments to worldly wealth (see Rococo Style). French painters François Boucher and Hyacinthe Rigaud proved to be remarkable chroniclers of opulence, as were English painters Thomas Gainsborough and Sir Joshua Reynolds. In the 18th century, female painters gained new importance, particularly in the field of portraiture. Notable female artists include French painter Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, Italian pastel artist Rosalba Carriera, and Swiss artist Angelica Kauffmann. E Neoclassicism, Romanticism, and Realism Vigée-Lebrun Self-Portrait French painter Marie-Louise-Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun was renowned for her beauty, charm, and wit, as well as for her artistic talents. Many of these qualities were reflected in her paintings, which tended to be graceful, delicate, and attractive, as can be seen in this self-portrait. It is in the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. Kimbell Art Museum/Corbis In the late 18th century and early 19th century, neoclassical artists depicted subjects attired in the latest fashions, which were derived from ancient Greek and Roman clothing styles. The artists used light that had great clarity to define texture and the simple roundness of faces and limbs. French painters Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Italian sculptor Antonio Canova were leading practitioners of neoclassical portraiture. See also Neoclassical Art and Architecture. Romantic artists, who worked during the first half of the 19th century, preferred to paint exciting portraits of inspired leaders and agitated subjects, using lively brush strokes and dramatic, sometimes moody, lighting. French artists Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault painted particularly fine portraits, the most noteworthy being Géricault's series of portraits of mental patients (1822-1824). Spanish painter Francisco de Goya painted some of the most searching and provocative images of the period, including Nude Maja (1800), which is believed to be a portrait. See also Romanticism. Portrait by Ingres French painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, like other artists of his time, considered portraiture inferior to history painting. Yet today he is known primarily for his outstanding portraits, such as this one of Madame Moitessier (1856). His portraits capture not only the ideals of beauty of his day but also the fashions in clothing and furnishings. By kind permission of the Trustees of the National Gallery London/Corbis The realist artists of the mid-19th century created objective portraits depicting ordinary people. French painter Gustave Courbet created many realistic portraits, while French artist Honoré Daumier produced many caricatures of his contemporaries. French artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec chronicled some of the famous dancers in the theater. French painter Édouard Manet, whose work hovers between realism and impressionism, was a portraitist of outstanding insight and technique. See also Realism. F Portraiture in the United States George Washington This portrait of United States President George Washington (1789-1797) was painted by the 18th-century artist Gilbert Stuart. Stuart painted a series of three portraits of Washington in 1795 and 1796, two of which were in the half-length style seen here. Stuart was renowned for his skill as a portrait painter, and many other famous government leaders sat for him. Art Resource, NY Immigrants who settled in North America continued the artistic traditions of their European ancestors. Because most of the early settlers shared an English heritage and Protestant values, English portraits became the models for American portraiture in the colonial period (17th century-18th century). The names of many American portraitists who worked in the 17th century are unknown. In the 18th century, John Smibert and John Singleton Copley produced many highly regarded portraits, and the commanding representations of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart also gained acclaim. During the 19th century, painter Thomas Eakins and sculptors Daniel Chester French and Augustus Saint-Gaudens were noted portraitists. Painter John Singer Sargent was the leading chronicler of the fashionable class in Europe during the late 19th century. See also American Art. G Impressionism and Postimpressionism Jeanne Samary This portrait of the actress Jeanne Samary was painted in 1879 by Pierre Auguste Renoir. The figure is bathed in light, and the artist's unique brushwork gives it a glowing quality. Although he was considered an impressionist, Renoir's work was always a little more traditional than that of his fellow impressionists. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York The impressionists of the late 19th century relied on family and friends to model for them and painted intimate groups and single figures represented either outdoors or in light-filled interiors. French painters Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Pierre Auguste Renoir created some of the most popular images of individual sitters. Noted for their shimmering surfaces and rich dabs of paint, these portraits are often disarmingly intimate and very appealing. American artist Mary Cassatt, who worked in France, was noted for her engaging portraits of mothers and children. Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh, both postimpressionist artists of the late 19th century to early 20th century, painted revealing portraits of people they knew, but they are best known for their powerful self-portraits. See also Impressionism; Postimpressionism. H Twentieth-Century and Contemporary Art Madame Zborowska Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani associated with artists living and working in Paris during the early 20th century, yet his work ultimately shows little connection to the famous art movements of his time. Rather, Modigliani developed an individualistic style that used sinuous lines, flat forms, and elongated proportions to depict his subjects. These elements combined to produce the almost classical effect seen in his figure studies and portraits, such as in Madame Zborowska (1918) . Giraudon/Art Resource, NY Early 20th-century artists expanded the repertoire of portraiture. Fauvist artist Henri Matisse produced powerful portraits using nonnaturalistic, even garish, colors for skin tones (see Fauvism). Spanish artist Pablo Picasso painted many portraits, including several cubist portraits, in which the subject is barely recognizable (see Cubism). Expressionist painters provided some of the most haunting and compelling psychological studies ever produced. German artists such as Otto Dix and Max Beckmann, as well as Austrian painter Oskar Kokoschka, produced notable examples of expressionist portraiture (see Expressionism). Mexican artists David Alfaro Siqueiros, Juan O'Gorman, and Frida Kahlo painted portraits that combine the modern influences of expressionism and surrealism with the imagery from popular indigenous art. Their work builds upon a long tradition of portraiture in Native American cultures. Ancient stone heads by the Maya displayed powerful images of individuality (although perhaps not of specific individuals). The so-called laughing clay sculptures of the Veracruz region in Mexico and the carved effigy vessels found in funerary mounds in North America testify to the remarkable observational skills of their makers. See also Pre-Columbian Art and Architecture; Native American Art; Latin American Painting. Portrait production in Europe and the Americas declined in the middle of the 20th century, a result of the increasing interest in abstraction and nonfigurative art. More recently, however, there has been a revival of portraiture. English artists such as Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon have produced powerful paintings in which the application of thick paint, called impasto, underscores the force of the subject's personality. Many contemporary American artists, such as Chuck Close, have made the human face a focal point of their work. See also Modern Art. I Self-Portraiture The first self-portraits in European art developed during the Renaissance, when artists depicted their own faces staring out from crowds in the backgrounds of narrative scenes. The first artist to systematically chronicle his own features in portraits was German painter Albrecht Dürer, whose self-portraits include a remarkable drawing of himself in the nude and a powerful portrait, Self-Portrait (1500, Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany), in which he presents himself as Jesus Christ. Rembrandt and van Gogh produced an unusually large number of self-portraits. As a genre, self-portraiture grew steadily in importance after the 17th century. J Photographic Portraits Portrait by Mathew Brady One of America's earliest commercial photographers, Mathew Brady opened his New York City studio in 1862 and took portraits of many of the nation's leading figures. However, his best-known contribution to photography consists of the 3500 pictures of battlefields, soldiers, and military camps taken under his direction during the American Civil War (18611865). Shown here is his portrait of General William T. Sherman, which is in the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian Institution/Art Resource, NY The development of photography during the 19th century and early 20th century changed the way in which portraiture was used. Photographic portraits were based on the actual appearance of the subject, whereas fine arts portraits had focused more on interpretive depictions of the subject. Moreover, while early photographic portraits were stilted and formal, requiring long, laborious sittings, as the technology advanced, the speed with which photographs could be produced allowed photographers to experiment creatively with photographic portraits. English photographer Julia Margaret Cameron was a master of the evocative Victorian portrait (see Victorian Style), and American photographer Mathew Brady chronicled soldiers during the American Civil War (1861-1865). In the 20th century the work of American photographer Dorothea Lange during the Great Depression of the 1930s exploited the photograph's power to portray real people in unadorned settings. American photographer Alfred Stieglitz was a major figure in early 20th-century photography; among his best-known portraits are those of his wife, painter Georgia O'Keeffe. American photographer Diane Arbus specialized in the bizarre, chronicling her eccentric subjects in an honest, straightforward manner. More recently, American photographer Cindy Sherman has experimented with the genre of portraiture by using images of herself to evoke new roles and personalities. VI PORTRAITURE IN AFRICA, ASIA, AND THE PACIFIC Physical resemblance to the subject is considerably less important in the traditional portraiture of African and Asian cultures than it is in traditional European art. A African Portraits Portraits assume a variety of forms in African art, including wood sculpture, masks, banners, carved memorial poles, and stuffed cloth mannequins. Group identity is paramount in the portraiture of Africa, a continent that is home to a vast and varied group of changing cultures. African portraits emphasize social identity rather than individual identity. In addition, portraits throughout Africa usually generalize and idealize their human images because these depictions often have a ritual and commemorative function. In some African cultures, the depiction of natural flaws denotes a less powerful being and is therefore to be avoided. For example, carved masks from the Baule, Côte d'Ivoire, with their stylized arched brows, simplified noses, and ovoid shapes, do not derive their identities from certain features on the masks. Rather, each mask derives its identity from its association with a specific dancer during an entertainment masquerade, or by having an assigned name. Artisans in the Kingdom of Benin, in present-day Nigeria, used sophisticated casting methods between the 15th and 18th centuries to fashion bronze heads depicting royalty, with elaborate headdresses and other accoutrements to denote the power of the subjects. See also African Art and Architecture. B Asian Portraits Otani Oniji as Eitoku Otani Oniji as Eitoku is a woodblock print by the Japanese artist T?sh ? sai Sharaku done in 1794-95 during the Edo period. This is a portrait of a kabuki actor in performance, his face reflecting the emotion of the scene. It is done in the Ukiyo-e style, which reached its peak in Japan in the 18th and 19th centuries. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Portraiture has a long tradition in Chinese art, although it has received little study. Evidence shows that murals with portraits existed as early as the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), but many scholars believe that Chinese portraiture originated before that time. Early Chinese artists conveyed the subject's character through such devices as clothing, pose, gesture, inscriptions, and the position of the figure in relation to others, believing that conduct defined a person. Later portraits delineate the facial features of their subjects more specifically. See also Chinese Art and Architecture. Japanese portraits, inspired by Chinese portraiture, were first produced in the Nara period (AD 710-784), but there is evidence of possible earlier examples in the preceding Asuka period (AD 552-710). Japanese portrait sculpture is largely Buddhist and, until the 19th century, much of it was memorial, commemorating venerated monks (see Buddhism). Japanese portraits can be considered in two broad categories: those portraits done with a knowledge of the subject's appearance, and those portraits, often executed long after the subject's death, based more on imagination than on visual fact. The Kamakura period (1185-1333) marked a high point in the quality and spiritual power of Japanese portraiture. The period also saw the development of secular portraits and the first appearance of Zen portraiture. Religious art in Japan generally declined during the 17th and 18th centuries, and the art of portraiture revived only after 1868, through contact with Western art. See also Japanese Art and Architecture. C Middle Eastern Portraiture Portraiture was a late development in Islamic culture, largely due to strict religious prohibition of image making, which was believed to verge on idol worship. Evidence suggests, however, that albums of royal portraits from the Sassanian Empire (AD 224-651) in pre-Islamic Persia (now Iran) survived the 8th-century Islamic conquest of the region. In most Islamic cultures, portraiture was rare until the 15th century, when Western artists spread the genre to the Iranian courts. At about the same time, portraiture spread to the Mughal court of India. By the Safavid period (1501-1722) in Iran, portraiture had become very popular, with several painters excelling at the practice. See also Islamic Art and Architecture; Iranian Art and Architecture; Indian Art and Architecture; Islam. D Oceanian Portraiture Oceania comprises a wide range of Pacific island cultures. Although representation of the human form plays a large role in art throughout the region, such representations do not necessarily function as portrayals of specific individuals. The artworks that perhaps most closely approach portraiture are the skulls that appear throughout Oceania, except in Micronesia. These skulls are remolded with the original facial features of an ancestor and are used for commemoration and consultation. The post figures made by the Maori of New Zealand, which are adorned with wigs and bear identifying tattoos and inscriptions, also depict ancestors. See also Oceanian Art and Architecture. Contributed By: Judith W. Mann Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.