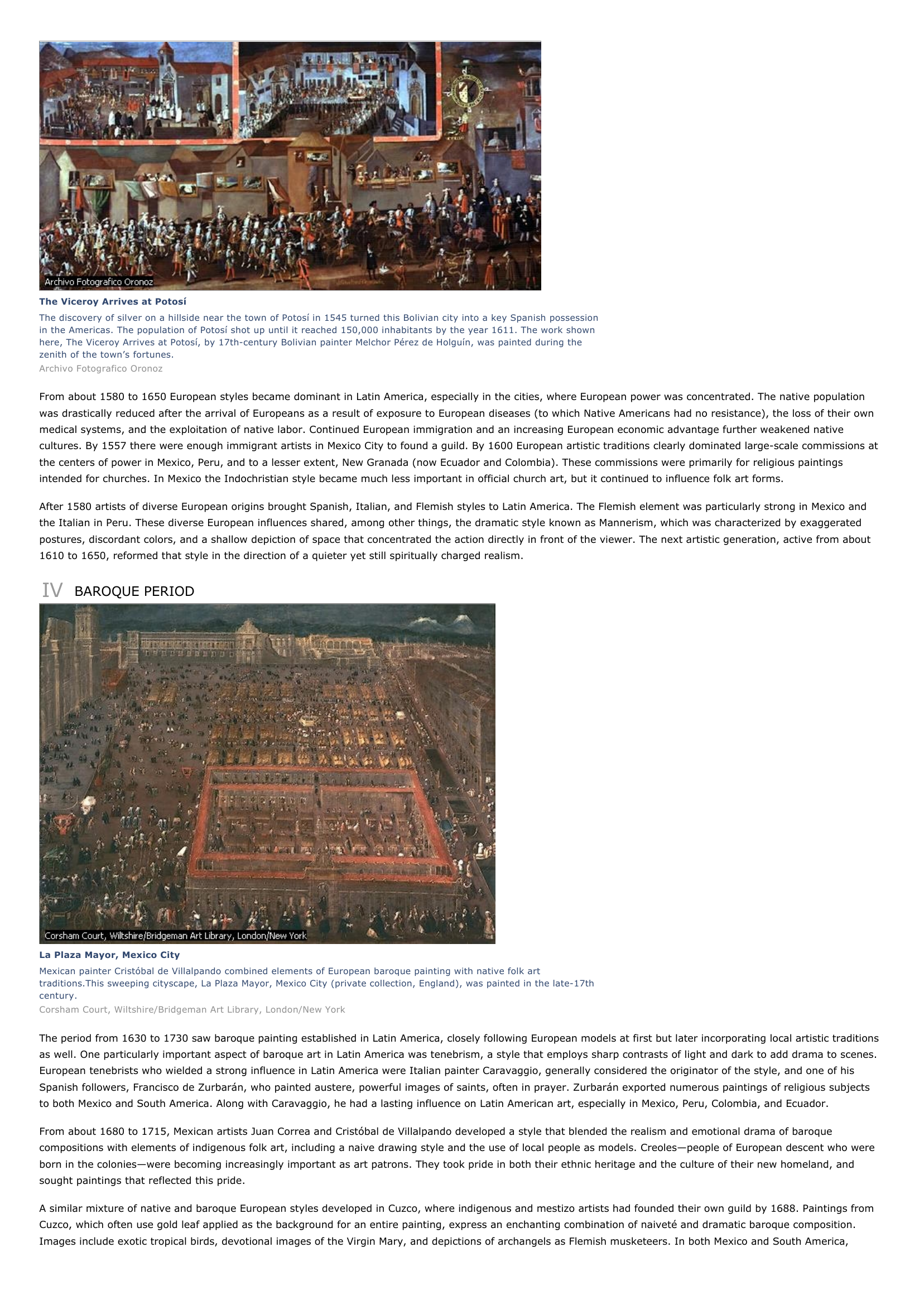

Latin American Painting I INTRODUCTION Diego Rivera Museum Gallery The studio of Mexican painter Diego Rivera is now maintained as an art museum in Mexico City. The artist's paintings, murals, and large-scale frescos often depicted Mexico's history and social issues. Rivera believed that art should serve and be accessible to the working people, and he painted many of his works on prominent public buildings. Rivera's influences include pre-Columbian artifacts, the cubist movement of Europe, and the work of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, Rivera's wife. Kelly-Mooney Photography/Corbis Latin American Painting, painting produced after the arrival of Spanish and Portuguese colonists in South America, Central America, and Mexico. The blend of European and indigenous (native) American cultures that characterizes Latin America today began to develop in the late 15th century. The Latin American artistic tradition was founded upon ancient, highly developed pre-Columbian civilizations, most notably those of the Aztec and Maya in Mexico and the Inca in Peru (see Pre-Columbian Art and Architecture). The Native American artistic traditions that European colonists encountered dated back centuries. Native painting traditions included manuscript illuminations; brilliantly colored, large-scale murals that decorated temples and illustrated historical events and ceremonies; and works of art in exotic media such as iridescent feathers. The strength of these traditions, along with the patronage of indigenous rulers and the numerical superiority of native peoples, ensured that colonial painting--at least initially--did not reflect European models alone but rather represented a mixture of European and indigenous artistic values. However, after about 1600, as the continued arrival of new settlers expanded the European presence, artistic styles increasingly reflected European models, especially in the urban centers. The overall structure of colonial art history is remarkably similar throughout Latin America, despite the enormous geographic area and the diverse traditions it encompasses. Most regions experienced similar stages from early colonial art to modern art, although the timetable varied greatly with location; some areas became colonized too late to experience the full sequence of stages. In addition Brazil, because it formed part of the vast Portuguese empire that extended to Africa and the Indian subcontinent, departed from the Hispanic pattern in many respects. Because the Portuguese imported large numbers of Africans to supplement native labor in Brazil, Brazilian culture became a blend of the cultures of three continents: Africa, South America, and Europe. Uniting all Latin American art from about 1580 was a tendency to revive the late Renaissance style of Mannerism, largely because it was the dominant style in Europe when European traditions became established in the Americas. From about 1630 on, the baroque style was dominant, although elements of Mannerism remained until the early 19th century. II EARLY COLONIAL PERIOD The early colonial period, which lasted until about 1580, saw a mixing of European and indigenous traditions. In Hispanic South America the Spanish term mestizo is generally applied to this mixture of artistic styles as well as to people of mixed European and Native American ancestry; in Mexico, this phenomenon is referred to as the Indochristian style. Some European settlements developed in what were already established administrative and artistic centers. Cuzco, an Inca city in southern Peru, and the Aztec capital Tenochtitlán, which became Mexico City, retained their prominence while new cities were also constructed (see Aztec Empire). The colonists brought with them the Roman Catholic religion, and the clergy set about converting the native population to Christianity. Many members of the clergy provided education for the native people as well, including training for native artists. Because of the clergy's active role, Christian and Native American artistic traditions coexisted in the art of this early period. For instance, a traditional native art form known as plumería, or feather mosaics, was adapted for the depiction of Christian subjects. Illuminated manuscripts called codices ranged in style from purely indigenous to almost completely European. A similar mixture of influences can be seen in the large-scale wall decorations of this period, such as those painted in the late 1500s for the church of San Agustín at Acolmán near Mexico City. In the cloister of the church, oversized images of enthroned saints and scenes of the suffering, crucifixion, and resurrection of Jesus Christ grace the upper walls, while indigenous designs are painted below. III EUROPEAN DOMINANCE The Viceroy Arrives at Potosí The discovery of silver on a hillside near the town of Potosí in 1545 turned this Bolivian city into a key Spanish possession in the Americas. The population of Potosí shot up until it reached 150,000 inhabitants by the year 1611. The work shown here, The Viceroy Arrives at Potosí, by 17th-century Bolivian painter Melchor Pérez de Holguín, was painted during the zenith of the town's fortunes. Archivo Fotografico Oronoz From about 1580 to 1650 European styles became dominant in Latin America, especially in the cities, where European power was concentrated. The native population was drastically reduced after the arrival of Europeans as a result of exposure to European diseases (to which Native Americans had no resistance), the loss of their own medical systems, and the exploitation of native labor. Continued European immigration and an increasing European economic advantage further weakened native cultures. By 1557 there were enough immigrant artists in Mexico City to found a guild. By 1600 European artistic traditions clearly dominated large-scale commissions at the centers of power in Mexico, Peru, and to a lesser extent, New Granada (now Ecuador and Colombia). These commissions were primarily for religious paintings intended for churches. In Mexico the Indochristian style became much less important in official church art, but it continued to influence folk art forms. After 1580 artists of diverse European origins brought Spanish, Italian, and Flemish styles to Latin America. The Flemish element was particularly strong in Mexico and the Italian in Peru. These diverse European influences shared, among other things, the dramatic style known as Mannerism, which was characterized by exaggerated postures, discordant colors, and a shallow depiction of space that concentrated the action directly in front of the viewer. The next artistic generation, active from about 1610 to 1650, reformed that style in the direction of a quieter yet still spiritually charged realism. IV BAROQUE PERIOD La Plaza Mayor, Mexico City Mexican painter Cristóbal de Villalpando combined elements of European baroque painting with native folk art traditions.This sweeping cityscape, La Plaza Mayor, Mexico City (private collection, England), was painted in the late-17th century. Corsham Court, Wiltshire/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York The period from 1630 to 1730 saw baroque painting established in Latin America, closely following European models at first but later incorporating local artistic traditions as well. One particularly important aspect of baroque art in Latin America was tenebrism, a style that employs sharp contrasts of light and dark to add drama to scenes. European tenebrists who wielded a strong influence in Latin America were Italian painter Caravaggio, generally considered the originator of the style, and one of his Spanish followers, Francisco de Zurbarán, who painted austere, powerful images of saints, often in prayer. Zurbarán exported numerous paintings of religious subjects to both Mexico and South America. Along with Caravaggio, he had a lasting influence on Latin American art, especially in Mexico, Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador. From about 1680 to 1715, Mexican artists Juan Correa and Cristóbal de Villalpando developed a style that blended the realism and emotional drama of baroque compositions with elements of indigenous folk art, including a naive drawing style and the use of local people as models. Creoles--people of European descent who were born in the colonies--were becoming increasingly important as art patrons. They took pride in both their ethnic heritage and the culture of their new homeland, and sought paintings that reflected this pride. A similar mixture of native and baroque European styles developed in Cuzco, where indigenous and mestizo artists had founded their own guild by 1688. Paintings from Cuzco, which often use gold leaf applied as the background for an entire painting, express an enchanting combination of naiveté and dramatic baroque composition. Images include exotic tropical birds, devotional images of the Virgin Mary, and depictions of archangels as Flemish musketeers. In both Mexico and South America, large-scale paintings for public buildings began to depict contemporary events. For example, The Procession of Corpus Christi (late 1600s, Museo de Arte Religioso, Cuzco), by an unidentified painter, meticulously records a religious procession and combines a naive, dreamlike quality with a luxurious sense of detail inspired by European baroque paintings. Toward the end of the 17th century, an alternative to the style of Correa and Villalpando developed in Mexico in the works of the brothers Nicolás and Juan Rodríguez Juárez, and one of their followers, José de Ibarra. Their gentle, pious works were influenced by a wide range of late baroque art in Europe, including French painting and the works of Spanish painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo. Murillo's combination of classical forms and soft, fluid brush strokes anticipated rococo art, and these influences set the tone for much of the art in 18th-century Mexico. A similar aesthetic eventually emerged in Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador. V 18TH CENTURY Juana Inés de la Cruz Mexican poet and scholar Juana Inés de la Cruz was noted for her poetry. She was first published in Spain in the late 17th century. This 1732 portrait is by Fray Miguel de Herrera. Art Resource, NY The Latin American economy boomed in the 18th century and new population centers developed, especially in mining areas. As artistic patronage spread from the traditional centers to the provinces, interest in folk and indigenous art forms grew. At the same time, improved communication with Europe allowed artists to keep abreast of international developments. An increase in the number of wealthy local patrons gave painters increased opportunities for portraiture and new secular subjects, such as city views and scenes of daily life. A popular genre of this period, castas painting, depicts people who characterize the new racial mixtures in the colonies, along with typical costumes, textiles, and agricultural products. Religious painting in the 18th century found itself competing in churches with the ornately carved and decorated new retablos (altar ensembles) (see Latin American Sculpture). Perhaps to compensate, some church artists of this period created smaller, simpler, more delicate works. Others produced monumental paintings to compete with the retablos, including immense wall compositions and ceiling paintings that give the illusion of opening onto the heavens. Brazil in particular built many new churches decorated with illusionistic ceilings and large-scale narratives painted on ceramic tiles. In Cuzco and Bolivia religious paintings were often gilded (their surfaces faced with gold leaf), as were decorative architectural elements. VI NEOCLASSICISM The final phase of colonial art, neoclassicism, arrived in the Americas under government patronage. Neoclassical art generally emulated the solemnity of ancient Greek and Roman models. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries the colonial governments established fine arts academies, which advocated the neoclassical style, in a number of cities, including Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Buenos Aires, Argentina; and Mexico City. Large-scale construction projects for new churches and government buildings gave the style a boost in these centers, as well as in Guatemala City, Guatemala; Bogotá, Colombia; Lima, Peru; Santiago, Chile; and other cities. Murals for the new buildings depicted religious, mythological, and historical subjects in a more solemn and reserved style that nevertheless retained some aspects of the baroque. A prominent artist of this period was Spanish-born Mexican painter Rafael Jimeno y Planes, who is known for a series of frescoes in the cupola of the Cathedral of Mexico. Among them is Assumption of the Virgin (1809-1810, now destroyed), which used baroque illusionism to set the stage for classically posed groups of saints. VII INDEPENDENCE Most of Latin America won independence in the early 19th century. Although independence brought no sudden change of style, it did bring social changes with longterm consequences for artists. Sources of patronage changed: The middle class, military, and government administrators emerged as important patrons, while the aristocracy and the church rapidly declined in importance as patrons. The dialogue between official art forms and folk art was reopened as new patrons looked for art that reflected local life. Scenes of everyday life, landscapes, and still lifes moved from the margins of artistic production to the center. VIII THE ACADEMIES José Gil de Castro's Simón Bolívar This portrait of Simón Bolívar, the principal leader in the struggle for South American independence from Spain, was painted by Peruvian soldier and artist José Gil de Castro in the 1820s. Gil de Castro was one of the first artists to paint the heroes of the South American Wars of Independence. The portrait is in the National Museum of Lima, Peru. SuperStock The art academies provided a conduit for patronage, continuity with both colonial and European artistic traditions, and a means by which Latin American artists could keep abreast of international developments. By the 1840s new art academies had opened in Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Argentina, and Chile. Only Peru had failed to convert its colonial school into an official institution, resulting in the continued provincialism of Peruvian art. Although the academies tended to import European artists as professors, they proved flexible in subject matter, allowing students to paint landscapes and scenes of daily life as well as the more highly regarded history paintings and portraits. Some of the most influential academicians included Mexican artists José María Obregón and Rodrigo Gutiérrez, who both painted historic subjects; Mexican society portraitists Pelegrín Clavé and ; the skillful portraitist and history painter Epifanio Garay in Colombia; and Martín Tovar y Tovar in Venezuela, who executed dignified portraits as well as murals of historic subjects. The influence of the academies was far-reaching, extending even into remote provinces, where local painters blended neoclassical and popular elements into simple yet powerful images. Battle of Carabobo In 1887 Venezuelan artist Martín Tovar y Tovar completed six canvas murals for the dome of the Salón Elíptico in the capitol building of Caracas, Venezuela. One of the outstanding murals (a detail of which is shown here) is dedicated to the Battle of Carabobo. Simón Bolívar's revolutionary army won the 1821 battle and entered Caracas having ensured freedom for Venezuela. age fotostock Painters also flourished outside the academies. The Peruvian soldier-artist José Gil de Castro (known as El Mulato Gil) painted military portraits, such as The Martyr Olaya (1823, Museo Nacional de Historia, Lima, Peru), in a naive but recognizably neoclassical style. Mexican artist Hermenegildo Bustos painted portraits that seem to capture the very essence of his provincial subjects. Other nonacademic masters, such as Pancho Fierro of Peru, came to prominence in the 19th-century costumbrista movement, which depicted native customs, often for the tourist trade. IX LANDSCAPE AND GENRE SUBJECTS José María de Velasco José María de Velasco was one of the greatest Mexican masters of landscape painting. Velasco's many views of rural Mexico include this painting, A Small Volcano in the Mexican Countryside (1887, Narodni Galerie, Prague). Narodni Galerie, Prague/Index/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Landscape painting flourished in 19th- and 20th-century Latin America as a result of a combination of factors. These included the interest of the academies; a sensitivity to landscape's potential for the symbolic expression of spiritual grandeur, which was a product of the European romantic movement; the exotic attraction of Latin American scenery for artists from Europe; and patriotic pride brought on by newfound independence. In Mexico, immigrant masters Daniel Thomas Egerton (from England) and Eugenio Landesio (from Italy) prepared the way for one of the greatest Mexican masters of landscape, José María de Velasco. Velasco's many views of the Valley of Mexico, site of the Aztec capital, and its twin volcanoes combine sweeping panorama with classical structure. Other important Latin American landscapists of the 19th century include Argentine Prilidiano Pueyrredón, Uruguayan Juan Manuel Besnes, Brazilian Agostinho José da Mota, and Ecuadorians Rafael Salas and Rafael Troya. Several South American painters combined academic, genre, and naturalistic interests. Francisco Laso's paintings of Peruvian natives engaged in everyday activities set the tone for indigenism, a movement that sought to recover native culture and portray native themes. Brazilian José Ferraz de Almeida Júnior painted similar subjects but employed classical poses and other academic conventions. Juan Manuel Blanes, an Argentine-born Uruguayan, blended landscape, contemporary history, genre, and allegory in his works. X MODERN ART Diego Rivera The art of mural painting reached its peak in the work of Diego Rivera, the most prolific and best-known of the Mexican muralists. This fresco, La Civilización Tarasca, deals with the customs of the indigenous people of Mexico, in this case the dyeing and decorating of fabric. National Institute of Bellas Artes/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York In the first two decades of the 20th century, Spanish modernists introduced Latin American painters to European styles of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including impressionism, postimpressionism, symbolism, and art nouveau. Mexican painter Saturnino Herrán, for example, used symbolism in his mural project, Our Gods (1904-1918, National Theater, Mexico City), in which nobly posed native Mexicans serve as powerful symbols of Mexican identity. Herran's mural project became a model for the many large-scale public murals that were commissioned in the 1920s. Modern art in Latin America found its own voice in these public murals created in the wake of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920). Defining this movement were three Mexican muralists--Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros--along with architect and muralist Juan O'Gorman and landscape painter Gerardo Murillo (known as Dr. Atl). Rivera in particular developed under the influences of European modernism, studying in Spain and in Paris, France, from 1907 to 1921 and working with Spanish artists Pablo Picasso and Juan Gris, who were experimenting with cubism. Cubist techniques such as the use of a diagonal grid as the basis of large-scale organization, abound in the works of Rivera and the other Mexican muralists. José Clemente Orozco Pre-Columbian Golden Age by José Clemente Orozco shows the power and emotion of his fresco work. His art, like that of Diego Rivera, reflects the Aztec roots of the Mexican people, but his style is more angular and flat; Orozco's use of strong lighting on the upraised arm of the figure on the right creates a dramatic effect. © 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOMAAP, Mexico City/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York The muralists expressed solidarity with the working and farming classes and shared the obsession with non-European aspects of Latin American culture that characterized the indigenism movement. These interests also inspired a simultaneous movement in photography and the graphic arts toward social realism, or the depiction of common people in a politically charged context. Rivera drew on both pre-Columbian sources and the traditions of Mexican folk art in a series of murals for the National Palace in Mexico City (1930-1932) that depict Mexico's history starting before European colonization. Siqueiros and Orozco also painted emotionally charged murals for public buildings, expressing their sympathy with workers and their opposition to political oppression in portrayals of Mexican history. Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros worked in the United States as well, where they exercised a strong influence on public art projects of the 1930s and 1940s, as well as on the early work of American abstract expressionist artists such as Jackson Pollock. In much of Latin American modern art, indigenism, social realism, and the stylistic aspects of the mural movement joined with an interest in surrealism. Surrealism, a movement in literature and the arts, emphasized the role of dreams and the unconscious in the creative process. To this, the Latin Americans added an interest in archetypes--images, ideas, or patterns that have come to be considered universal models. These archetypes, which appear in mythology, religion, and art, make up what Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung and others termed the collective unconscious. Archetypes, especially those found in Native American art, have continued to fascinate Latin American painters of the 20th century. Self-Portrait with Small Monkey Twentieth-century Mexican painter Frida Kahlo is best known for her unusual self-portraits. In these works her impassive stare generally masks her feelings. Kahlo's style borrows from Mexican folk art and her paintings incorporate representations of Mexican flora and fauna as well as references to Mexico's pre-Columbian civilizations, as seen here in Self-Portrait with Monkey (1945, private collection). Schalkwijk/Art Resource, NY As early as 1912, Mexican painter Francisco Goitia brought to Mexico a presurrealist style influenced by the satirical art of Spanish painter Francisco de Goya and Belgian painter James Ensor. A blending of social realism and surrealism that has been called social surrealism developed in the 1920s and 1930s in the paintings of Mexicans Antonio Ruíz (known as El Corzo) and Agustín Lazo and those of Argentine painter . This was paralleled by the more personal, mythic vision of Argentine painter and the dreamy landscapes of Venezuelan . Mexican painter Frida Kahlo blended naive folk imagery, psychological intensity, and dreamlike subjects into powerful compositions that have much in common with the art of European surrealists Giorgio di Chirico and Max Ernst. Kahlo's many self-portraits project a sense of feminine strength, a quality they share with the paintings of María Izquierdo, also Mexican. Rufino Tamayo Mexican artist and sculptor Rufino Tamayo stands outside the museum dedicated to his work, located in Mexico City. An early post at the National Archaeology Museum in Mexico City brought him in contact with the pre-Columbian objects that would later influence his art. His work, colorful and often abstract, also shows the influence of European cubism. A prominent public figure, Tamayo worked in government and teaching positions throughout his career. Sergio Dorantes/Corbis In 1938 the French leader of the surrealist movement, André Breton, visited Mexico. This visit, together with a subsequent flood of surrealist exiles to the United States and Latin America during World War II (1939-1945), had a lasting impact on art in the Americas. Among the immigrants were painters (from England) and (from Spain), both of whom settled permanently in Mexico and developed an art of dreamlike images known as magic realism. XI ABSTRACT ART Pettoruti's Avenida Arbolada Argentina painter Emilio Pettoruti was born in La Plata in 1892 and belonged to the cubist movement in Latin America from 1914 on. Shown here is Avenida arbolada (Tree-Lined Street), which demonstrates the splitting of forms characteristic of analytical cubism. © Fundacion Pettoruti/Christie's Images Abstract art in Latin America also established strong ties to surrealism. In the 1920s in Brazil, Tarsila do Amaral painted abstract compositions that blend cubism and surrealism with native Brazilian subject matter. A similar combination of elements marks the art of Mexican painter . In Uruguay, Joaquín Torres-García and his followers, known as the Montevideo School, developed an abstract art with strong connections to surrealism and to the spare geometries of the Russian constructivist and German Bauhaus movements. The Unknowing The paintings of Chilean-born artist Roberto Matta Echaurren incorporate organic, symbolic, and mechanical forms in a mysterious space. Matta was a member of the surrealist movement and emphasized the role of chance and the subconscious in the creative process. The Unknowing (1951) is in the Museum of Modern Art in Vienna, Austria. © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photo: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY After 1940 the abstract surrealism of Torres-García and Amaral came to dominate Latin American art, especially the works of Wifredo Lam of Cuba and Roberto Matta Echaurren of Chile. Matta also played a role in the development of abstract expressionism in the United States. Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo applied the lessons of cubism and surrealism to Mexican themes, although he avoided political messages in his work, unlike many earlier artists. The paintings of Lam, Matta, and Tamayo represent several major shifts in Latin American art after 1945: from the public stance of the muralists to private concerns, from strident nationalism to internationalism, and from the struggle for social change to personal explorations of ethnic origins and archetypal myths. The surrealist movement continued unabated in Latin America at the end of the 20th century, influencing contemporary artists as diverse as Roberto Aizenburg of Argentina, Fernando Botero of Colombia, Claudio Bravo of Chile, and Nahum B. Zenil of Mexico, of Nicaragua, and Tomás Sánchez of Cuba. Contributed By: Marcus B. Burke Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.