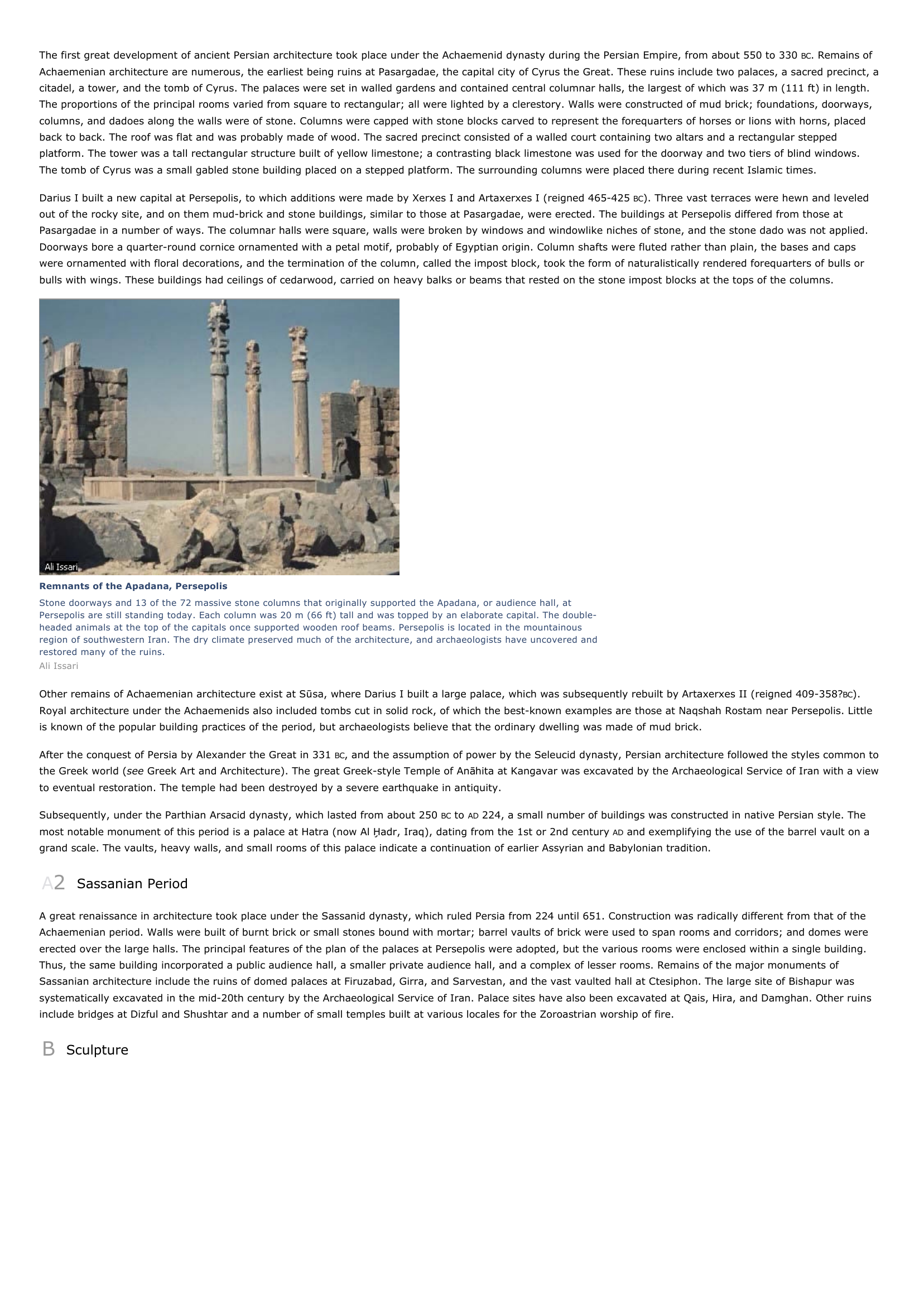

Iranian Art and Architecture I INTRODUCTION Iranian Art and Architecture, the visual arts of Iran. Although in the West this has been traditionally known as Persian culture, the inhabitants of the country have long called it Iran and themselves Iranians, rather than Persians. In accordance with popular usage, however, the term Persian will be used in this article to refer to the period before the advent of Islam in the 7th century II AD--that is, the period of the ancient Persian empires--as well as the preceding prehistoric times. ANCIENT PERIOD Griffin Bracelet This gold armlet, made in Persia during the Achaemenid dynasty, is part of the Treasure of the Oxus, a collection of decorative objects from the Persian Empire now located in the British Museum in London, England. The armlet was originally inlaid with glass and colored stones; its most distinctive features are the huge winged griffins, whose heads form the ends of the piece. Large animal-headed armlets such as this one were highly prized by the Achaemenids; similar pieces are shown being offered to the king on the reliefs of the Apadana stairs. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Ceramics and clay figurines were the chief artworks of the prehistoric period, and architecture and sculpture predominated during the period of the first two Persian empires (6th century BC to 7th century AD ). After the Arab conquest and the introduction of Islam in the 7th century AD, sculpture was little practiced but architecture flourished. Painting became a major art in the period from the 13th to the 17th century. In the 20th century these ancient arts were being revived, and traditional forms were combined with Western technology and contemporary materials. A Architecture Prehistoric architecture in Iran remains little known but has gradually begun to come to light since World War II. Among the earliest examples are a number of small houses of packed mud and mud brick found at several Neolithic sites in western Iran: Tepe Ali Kosh, Tepe Guran, Ganj Dareh Tepe, and Hajji Firuz Tepe. These sites show that small villages made up of one-room houses and storage structures were already established along the western border of the country by 6000 at Tal-i Bakun, near Persepolis, and Tal-i Iblis and Tepe Yahya, near Kerm?n, show that by 4000 BC BC. Excavations buildings with a number of rooms were being erected and grouped into villages or small towns. All of these structures indicate that the traditional building techniques using packed mud and sun-dried mud brick had already been invented. At Shahr-i Sokhta in Seistan an elaborate Bronze Age palace (circa 2500 BC) was excavated. The plans of these remains show a steady growth in complexity ending with the establishment of important commercial centers on the plateau. At the end of the 2nd millennium BC, the Iranian tribal groups, including the Medes and Persians, spread over the plateau and displaced or absorbed the indigenous inhabitants. The architecture and crafts of this Iron Age period, which immediately preceded the founding of the Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great, have been brought to light by excavations near Kangavar (Godin Tepe and Babajan Tepe), near Hamad?n (Nush-i Jan Tepe), and at Zendan-i Suleiman and Tepe Hasanlu in northwestern Iran. These sites revealed for the first time a tradition of building in which large columnar halls are used as a central feature. The columns were of wood set on stone slabs, while the buildings themselves were of uncut stone and mud-brick construction. Stairways and terraces, along with other features, formed the prototypes for later developments in the imperial architecture of Pasargadae and Persepolis. The buildings at Nush-i Jan Tepe and Godin Tepe are almost certainly Median in origin and are the first structures excavated belonging to the Medes. These discoveries confirm the generalized descriptions of battlements and palaces found in the literary sources, especially of the Greek historian Herodotus. A1 Achaemenian Period Throne Hall Relief, Persepolis Carved relief sculptures decorated many of the stone door and window jambs at Persepolis in Iran, including this entrance to the Throne Hall. The Throne Hall was begun by Xerxes in the early 5th century bc as a place to receive visiting representatives from all the nations ruled by the Persian Empire. The king is shown seated at the top of the relief as a dignitary approaches. Guards fill the rows below. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York The first great development of ancient Persian architecture took place under the Achaemenid dynasty during the Persian Empire, from about 550 to 330 BC. Remains of Achaemenian architecture are numerous, the earliest being ruins at Pasargadae, the capital city of Cyrus the Great. These ruins include two palaces, a sacred precinct, a citadel, a tower, and the tomb of Cyrus. The palaces were set in walled gardens and contained central columnar halls, the largest of which was 37 m (111 ft) in length. The proportions of the principal rooms varied from square to rectangular; all were lighted by a clerestory. Walls were constructed of mud brick; foundations, doorways, columns, and dadoes along the walls were of stone. Columns were capped with stone blocks carved to represent the forequarters of horses or lions with horns, placed back to back. The roof was flat and was probably made of wood. The sacred precinct consisted of a walled court containing two altars and a rectangular stepped platform. The tower was a tall rectangular structure built of yellow limestone; a contrasting black limestone was used for the doorway and two tiers of blind windows. The tomb of Cyrus was a small gabled stone building placed on a stepped platform. The surrounding columns were placed there during recent Islamic times. Darius I built a new capital at Persepolis, to which additions were made by Xerxes I and Artaxerxes I (reigned 465-425 BC). Three vast terraces were hewn and leveled out of the rocky site, and on them mud-brick and stone buildings, similar to those at Pasargadae, were erected. The buildings at Persepolis differed from those at Pasargadae in a number of ways. The columnar halls were square, walls were broken by windows and windowlike niches of stone, and the stone dado was not applied. Doorways bore a quarter-round cornice ornamented with a petal motif, probably of Egyptian origin. Column shafts were fluted rather than plain, the bases and caps were ornamented with floral decorations, and the termination of the column, called the impost block, took the form of naturalistically rendered forequarters of bulls or bulls with wings. These buildings had ceilings of cedarwood, carried on heavy balks or beams that rested on the stone impost blocks at the tops of the columns. Remnants of the Apadana, Persepolis Stone doorways and 13 of the 72 massive stone columns that originally supported the Apadana, or audience hall, at Persepolis are still standing today. Each column was 20 m (66 ft) tall and was topped by an elaborate capital. The doubleheaded animals at the top of the capitals once supported wooden roof beams. Persepolis is located in the mountainous region of southwestern Iran. The dry climate preserved much of the architecture, and archaeologists have uncovered and restored many of the ruins. Ali Issari Other remains of Achaemenian architecture exist at S? sa, where Darius I built a large palace, which was subsequently rebuilt by Artaxerxes II (reigned 409-358?BC). Royal architecture under the Achaemenids also included tombs cut in solid rock, of which the best-known examples are those at Naqshah Rostam near Persepolis. Little is known of the popular building practices of the period, but archaeologists believe that the ordinary dwelling was made of mud brick. After the conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great in 331 BC, and the assumption of power by the Seleucid dynasty, Persian architecture followed the styles common to the Greek world (see Greek Art and Architecture). The great Greek-style Temple of An?hita at Kangavar was excavated by the Archaeological Service of Iran with a view to eventual restoration. The temple had been destroyed by a severe earthquake in antiquity. Subsequently, under the Parthian Arsacid dynasty, which lasted from about 250 BC to AD 224, a small number of buildings was constructed in native Persian style. The most notable monument of this period is a palace at Hatra (now Al ?adr, Iraq), dating from the 1st or 2nd century AD and exemplifying the use of the barrel vault on a grand scale. The vaults, heavy walls, and small rooms of this palace indicate a continuation of earlier Assyrian and Babylonian tradition. A2 Sassanian Period A great renaissance in architecture took place under the Sassanid dynasty, which ruled Persia from 224 until 651. Construction was radically different from that of the Achaemenian period. Walls were built of burnt brick or small stones bound with mortar; barrel vaults of brick were used to span rooms and corridors; and domes were erected over the large halls. The principal features of the plan of the palaces at Persepolis were adopted, but the various rooms were enclosed within a single building. Thus, the same building incorporated a public audience hall, a smaller private audience hall, and a complex of lesser rooms. Remains of the major monuments of Sassanian architecture include the ruins of domed palaces at Firuzabad, Girra, and Sarvestan, and the vast vaulted hall at Ctesiphon. The large site of Bishapur was systematically excavated in the mid-20th century by the Archaeological Service of Iran. Palace sites have also been excavated at Qais, Hira, and Damghan. Other ruins include bridges at Dizful and Shushtar and a number of small temples built at various locales for the Zoroastrian worship of fire. B Sculpture Carved Stairway of Persepolis The site of the ancient city of Persepolis, an ancient capital of Persia that is now located in Iran, contains the remains of various monumental buildings. Bas-relief sculptures along the grand stairway, dating from the 6th century bc, depict Persian guards. Paul Almasy/Corbis In the first great period of Persian art, during the reign of the Achaemenids, sculpture was practiced on a monumental scale. About 515 BC, Darius I had a vast relief and inscription carved on a cliff at Behistun. The relief shows him triumphing over his enemies as Ahura Mazda, the chief Zoroastrian deity, looks on. The carving was derived in plan and detail from Assyrian models, but the naturalistic treatment of the drapery and the eyes was original. At Persepolis, sculpture was an important adjunct to the architecture. In addition to the sculptured animal capitals on the columns, which were a dominant feature of the interiors of the buildings, friezes representing lions were set on the exterior cornices. Doorjambs were carved with reliefs of the king, and staircases were decorated with friezes of royal guards and tribute bearers carved in low relief. The main gateway to the city was flanked by a pair of huge bulls with human heads, carved in high relief. Glazed Brick Panels from S?sa This glazed-brick relief of an imaginary beast is part of the palace at S?sa (6th century bc), in present-day Iran. The use of bricks glazed in blue, green, white, and yellow for the creation of decorative friezes is a tradition that began in ancient Assyria and Babylonia. Gianni Dagli Orti/Corbis The decoration of the palace at S? sa consisted of stone reliefs in the style of those at Persepolis, and panels of bricks glazed blue, green, white, and yellow. The use of glazed bricks continued a tradition that was first established in Assyria and Babylonia. The glazed-brick panels at S? sa portrayed soldiers, winged bulls, sphinxes, and griffins. The best known of these panels make up the Frieze of Archers (Louvre, Paris). Achaemenian sculpture in relief is further exemplified at Naqshah Rostam, where four royal tombs were hewn out of the rock. At each tomb the face of the cliff was carved to represent the facade of a palace; above the palace, figures support a dais on which the king stands worshiping the gods. After the conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great, Greek influence, in its late, Hellenistic phase, was predominant in the arts of Persia. Examples include fragments of bronze sculpture found at Shami, and the Parthian sculptural reliefs at Behistun. The second great period of Persian art began, as noted, with the reign of the Sassanid dynasty in AD 224. A single example of sculpture in the round has survived from this period: a colossal standing figure of a king near Bishapur. A few statuettes have also survived, but the characteristic sculptural work, as in Achaemenian times, was the relief cut in rock. The best-known examples are colossal reliefs at Naqshah Rostam portraying the Persian kings Ardashir I and Shapur I (reigned 241-72) mounted on horses. A similar equestrian relief at Taq-i-Bustan represents another Persian king of this dynasty, Khosrau II. Following the Sassanian period, sculpture ceased to exist as a major art. C Pottery, Metalwork, and Weaving Sassanian Vase This stone vase, probably made during the Acaemenian period, has a foot, cap, and spout all made of cast bronze. The letters on the body of the vase stand for the Medici family, who apparently bought this piece in the 16th century and remounted it, adding their initials. Scala/Art Resource, NY The earliest examples of Persian decorative arts date from the late 7th millennium BC and consist of animal and human female figures fashioned in clay. The female figurines, found at Tepe Sarab near Kerm?nsh?h (B? khtar?n), are complex objects made of many small pieces fitted together on small dowels. The thighs and breasts of the figures are exaggerated, and the heads are reduced to small pegs. In contrast to the highly stylized and abstracted human figures are quantities of animal figurines done in an extremely natural style. The second great development in prehistoric art occurred during the 4th millennium, when a variety of painted pottery styles appeared on the plateau. The vessels are usually red or buff in color and are covered with animal figures, often goats, painted in black. The pottery was found alongside small objects such as stamp seals and small instruments of copper including pins and chisels. During the 3rd millennium, burnished gray pottery was manufactured in northeastern Persia along with a great amount of cast copper objects such as axes, decorated pins, figurines, and the like. Painted pottery continued to be made in other parts of the country except in northern Iranian provinces of Azerbaijan, where black and gray burnished wares appeared, decorated in many instances with geometric patterns incised into the surface and then filled with a white paste. About 1300 BC gray burnished pottery appeared over the whole of the north, perhaps originating in the northeast, and probably associated with the spreading Indo-Iranian tribes. About 800 BC painting again revived, with geometric patterns, animals, and human figures represented. Khosrau I Considered one of Persia's greatest rulers, Khosrau I is depicted in the center of this contemporary decorative plate. In 531 he began a series of battles with the Byzantine Empire that led to the expansion of Persia's borders. Khosrau also streamlined government administration and reformed the tax system. Giraudon/Art Resource, NY Beginning at the end of the 2nd millennium and continuing to the middle of the 1st millennium a great florescence of bronze casting occurred along the southern Caspian mountain zone and in Lorest?n. Harness trappings, horse bits, axes, and votive objects were made in large quantities and reflected a complex animal style created by combining parts of animals and fantastic creatures in various forms. Luxurious works of decorative art were produced during the Achaemenian period, including ornaments and vessels of gold and silver, stone vases, and engraved gems. A collection of these objects, called the Treasure of the Oxus, is exhibited at the British Museum, London. Sassanian metalwork was highly developed, the most usual objects being shallow silver cups and large bronze ewers, engraved and worked in repoussé. The commonest themes were court scenes, hunters, animals, birds, and stylized plants. The largest collection of these vessels is in the Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg; other examples are in museums in Paris, London, and New York City. Silk weaving was a flourishing industry under the Sassanid dynasty. The designs, consisting of symmetrical animal, plant, and hunter patterns framed in medallions, were imitated throughout the Middle East and also in medieval Europe. Even after the Arab conquest, Sassanian silks and metalware continued to be manufactured, and Sassanian designs strongly influenced artists in Byzantium to the west and as far as Eastern Turkistan to the east. III ISLAMIC PERIOD After the conquest of Persia by the Arabs in 641, Iran became part of the Islamic world. Iranian artists adjusted to the needs of Arabic Islamic culture, which was in turn influenced by Iranian traditions. Architecture continued to be a major art form, but because Islamic tradition condemned the three-dimensional representation of living things as idolatrous (at least in a religious context; see Islamic Art and Architecture), sculpture declined. Painting, on the other hand, not affected by proscription of the human form, reached new prominence, and the decorative arts, too, continued to thrive. A Architecture Courtyard, Madrasa, E? fah?n A madrasa is a place for learning and prayer. This view into the courtyard of the Madrasa Chah? r B? gh in E? fah ? n, Iran, shows the domed mosque, central pool, and rooms around the courtyard for study and accommodation. The madrasa was built from 1706 to 1714. Art Resource, NY The mosque became the major building type in Iranian architecture. The established style of vaulted construction was continued; common features were the pointed arch, the ogee arch, and the dome on a circular drum. Outstanding examples of early Islamic Iranian architecture include the Mosque of Baghd?d built in 764, the Great Mosque at Samarra erected in 847, and the early 10th-century mosque at Nayin. The Mongols destroyed much of the early Islamic architecture in Iran, but after their conquest of Baghd?d in 1258, building was resumed according to Iranian traditions. Subsequently, a number of the most notable buildings in the history of Iranian architecture were erected. They include the Great Mosque at Veramin, built in 1322; the Mosque of the Imam Reza at Meshad-i-Murghab, erected in 1418; and the Blue Mosque at Tabr?z. Other major structures include the mausoleums of the Turkic conqueror Tamerlane and his family at Samarqand, the Royal Mosque at Meshad-iMurghab, and the vast madrasas, or mosque schools, at Samarqand, all of them erected during the 15th century. Mosaic Decoration The use of colored tile in architectural decoration has a long history in the Middle East. This intricate design was adjusted to the complex shape of the niches in the interior of a madrasa, or religious seminary in E?fah ? n, Iran. SEF/Art Resource, NY Under the Safavid dynasty (1501-1722), a vast number of mosques, palaces, tombs, and other structures were built. Common features in the mosques were onionshaped domes on drums, barrel-vaulted porches, and pairs of towering minarets. A striking decoration was the corbel, a projection of stone or wood from the face of a wall, used in rows and tiers. These corbels, arranged to appear as series of intersecting miniature arches, are usually called stalactite corbels. Color was an important part of the architecture of this period, and the surfaces of the buildings were covered with ceramic tiles in glowing blue, green, yellow, and red. The most notable Safavid buildings were constructed at E?fah?n (Isfahan), the capital at that period. The city, laid out in broad avenues, gardens, and canals, contained palaces, mosques, baths, bazaars, and caravansaries. Imam Mosque, E? fah?n The 17th-century royal mosque in the center of the city of E? fah? n, Iran, is known as the Imam Mosque (Masjed-é Em ?m). Clad in ceramic tiles, this masterpiece of Persian architecture was built during the reign of Abbas I. Adam Woolfitt/Woodfin Camp and Associates, Inc. Since the 18th century, the architectural styles of western Europe have been adopted to an increasing degree in Iran. At the same time, traditional forms have remained vital, and native and imported elements have often been combined in the same building. Recently, unadorned steel and concrete structures, similar to those seen in other parts of the modern world, have been built as dwellings, public buildings, and factories. B Painting Persian Manuscript During the rule of the Abbasid caliphs, from 750 to 1258, Islamic culture flourished. This 13th-century Persian manuscript was created during this period. Islamic art used input from neighboring cultures including the Persians in the development of a cohesive Islamic style of art. Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris/Laurie Platt Winfrey, Inc./Woodfin Camp and Associates, Inc. Painting in fresco and the illumination of manuscripts (see Illuminated Manuscripts) were practiced in Iran at least as early as the Sassanian period, but only fragments of the work have survived. In Islamic Iran, painting was one of the most important arts. Manuscripts of the Qur'an (Koran) in the Arabic Kufic script were executed on parchment rolls at Al Ba? rah and Al K?fah at the end of the 7th century. These manuscripts did not contain painted scenes but depended for their effect on the beauty of the calligraphy. Ornamental calligraphy was widely practiced in the 8th and 9th centuries. Painting and illumination became important elements in the decoration of manuscripts in the 9th century. With the introduction in the 10th century of paper for making books, the forms and varieties of religious and secular books increased greatly. Laila and Majnun at School Laila and Majnun at School (1494) was painted by Bihzad, one of the great Persian miniature artists from Her? t (now in Afghanistan). The flat, layered perspective shows the influence of Chinese landscapes. The gold background is unusual for a painting done before the 16th century, and the faces are drawn with a sense of grace not often seen in such work. The juxtaposition of inside and outside and the way in which parts of the picture spill over the borders is particularly notable. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York In the 12th century, a school of painting at Baghd? d became known for its manuscripts of scientific works, fables, and anecdotes, illustrated with miniature paintings. In the 13th century the influence of Chinese landscape painting, introduced after the Mongols came to power in Iran, became apparent. Paintings of stories, legends, and historical events, often occupying whole pages and pairs of pages, illustrated books devoted to poems and world histories. The text was usually written in Persian rather than Arabic as had previously been customary. In the 14th century Baghd?d and Tabr?z were the main centers for painting. Subsequently, Samarqand, Bukhara (Bukhoro), and Her?t also became important centers. In general the paintings consisted of figural scenes of hunting, warfare, or palace life and of landscapes of jagged rocks, single trees, and little streams bordered by flowers. At the beginning of the 14th century the backgrounds of the paintings were usually red; later they were more often blue, and at the end of the century gold backgrounds became common. Persian Miniature This example of a Persian miniature painting is by Aqa Mirak, who was a court painter of Tahmasp (1524-1576). Mirak illustrated secular books of the Timurid and Safavid periods. This piece features the bright colors and flattened space typical of this style. It is an illustration of a story; possibly a fight has just occurred, and the loser is on his back. Just above the center of the painting a gardner works industriously. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York The best-known Iranian miniature painter was Bihzad, the greatest artist of the end of the Mongol and the beginning of the Safavid periods. He was head of the academy of painting and calligraphy at Her?t until 1506, when he went to Tabr?z and became the royal librarian. Bihzad's paintings are characterized by rich color and realistic figures and landscapes. He differentiated the figures in group scenes, and his portraits are strongly individual. Many painters studied with him, including the celebrated artists Mirak and Sultan Mohammed, and his style was imitated throughout Iran, Turkistan, and India. Among the few extant manuscripts illustrated by Bihzad are the History of Tamerlane (1467), now in the Princeton University Library, and the Fruit Garden (1487), a book of poems now in the Egyptian Library, Cairo. Ardashir and Ardowan Persia was one of the first countries to be converted to Islam. This scene, The Combat of Ardashir and Ardowan, from a 14th-century Persian manuscript, depicts a battle between a Persian king and a Muslim warrior. Although the conflict took place in the mid-7th century, the costumes shown are those of the 14th century. Francis G. Mayer/Photo Researchers, Inc. Portrait painting became an important art form during the 16th century. One of the most distinguished portraitists was Ali Reza Abbasi, who delineated his figures with spare but expressive brush strokes. Most of his paintings represent single figures, but he also painted realistic group scenes of pilgrims and dervishes. In the late 16th century and in the 17th century, monochrome ink drawings brightened with touches of red and gold replaced the jewel-like polychrome paintings of the earlier manuscripts. After the 17th century, Iranian artists copied European paintings and engravings, and the native traditions declined. Paintings of conventional Iranian themes in brilliant colors on lacquer boxes and book covers became a handicraft industry in the 19th century, and the lacquerware was exported in large quantities to western Europe. This industry was still flourishing in the late 20th century. Modern imitations of 16th-century miniature paintings were also common, but no contemporary national style of painting had emerged. C Decorative Arts Persian Carpet Iran has long been a center of rug-weaving. This carpet, featuring a central medallion with animals and flowers, dates from the second half of the 16th century and is now in the Museum for Islamic Art in Berlin, Germany. Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY Techniques of weaving, metalwork, and pottery, developed during the Sassanian period, were practiced throughout subsequent Iranian history. The weaving of rugs, for which Iran has been especially noted, was encouraged by the Sassanids and has continued to be an important artistic skill until the present time. Rugs were made in small villages and in court workshops. The design of carpets used in mosques or for private prayer usually consisted of a medallion or arch within a field surrounded by a border, the whole covered with delicate floral forms. Carpets for secular use might have animal or human figures (see Rugs and Carpets). Metalwork was also important. Fine bronze, brass, and copper wares inlaid with silver and engraved were made in Mosul and other centers. Pottery of outstanding quality was made during the Islamic period, especially in the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries. The potters of Rayy and K?sh?n made minae ware with delicate polychrome figures, lusterware with metallic glaze decoration, and wares with strong, dark naturalistic motifs under a clear or turquoise glaze. See also Indian Art and Architecture. Contributed By: Robert H. Dyson Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.