Indian Music I INTRODUCTION Classical Dance of South India The southern Indian kathakali is a dance drama that dates from the 17th century.

Publié le 12/05/2013

Extrait du document

«

Sangita Ratnakara, was written in the 13th century.

However, subsequent writers tended to focus on the emotional connotations of individual ragas, associating them with moods, performance times, colors, and deities, and grouping them in terms of families.

The modern theoretical system began in the 16th century, when ragasbegan to be classified according to scale—72 in the Karnāṭak system and 10 principal ones in the Hindustani.

The 72 mela, as the Karn āṭak scales are called, are derived through permutations of the accepted notes of south Indian music.

The 10 thaats of north Indian music, meanwhile, are based on prevalent raga practice in Hindustani music, 9 of which fit into a circle similar to that of the Western system of keys.

A raga can be performed both in free time and in measured time.

In free time, called alapa (or alapana ), the melodic features of a raga are explored gradually in their natural rhythm or flow, often accompanied only by a drone played on the tambura or on an electronic shruti box (double-reeded wind instrument).

A section with a pulse but no time measure, called jor in the north and tanam in the south, often precedes a raga in measured time.

One of several possible tala (time measures) is used.

A tala consists of a repeating number of time units ( matra, or counts) that form a cyclical pattern; within this cycle, specific points receive different degrees of stress.

Tala thus involves both a quantitative element (time units or counts) and a qualitative element (accent or stress).

The Hindustani jhapatala, for example, has 10 time units, divided as follows: 2 + 3 + 2 + 3, marked by a drummer and also often counted by finger movements, claps, or waves during performance.

A tala isintroduced by a set composition, which is followed by variations and improvisations based melodically on the raga and constrained rhythmically by the tala .

How much emphasis the alapa is given depends to some extent on each performer's inclination, but also relates to the compositional form that follows.

In the Karn āṭakform kriti, much importance is placed on the composition and its usually devotional text, and the alapa section, accordingly, is generally short; in contrast, in the now less common Karn āṭak form ragam-tanam-pallavi, the alapa is much longer.

In the Hindustani khyal, the usual vocal concert form found in north India today, the composition is generally considered subordinate to the improvisations, and a lengthy introductory section called bada (big) khyal is performed in a time measure so extremely slow and abstract that the vocalizations sound almost like alapa .

This is usually followed by a chhota (small) khyal in fast tempo, with virtuosic runs to the vowel a.

The khyal appears to have replaced the austere, formerly more prominent dhrupad, probably because it accommodates a greater display of virtuosity and imagination.

Both Hindustani and Karn āṭak traditions also have vocal forms derived from dance and considered lighter in character.

These forms, with their dance-rooted rhythms, are generally performed at the close of concerts, with little or no foregoing alapa .

In the Karn āṭak system, instrumental music is based on vocal forms.

The gat of Hindustani music, in contrast, is a specifically instrumental composition based on the plucking patterns of stringed instruments, especially the sitar.

A long alapa and other nonmeasured pulsing sections (jor and jhala ) often precede the gat.

III CLASSICAL INSTRUMENTS

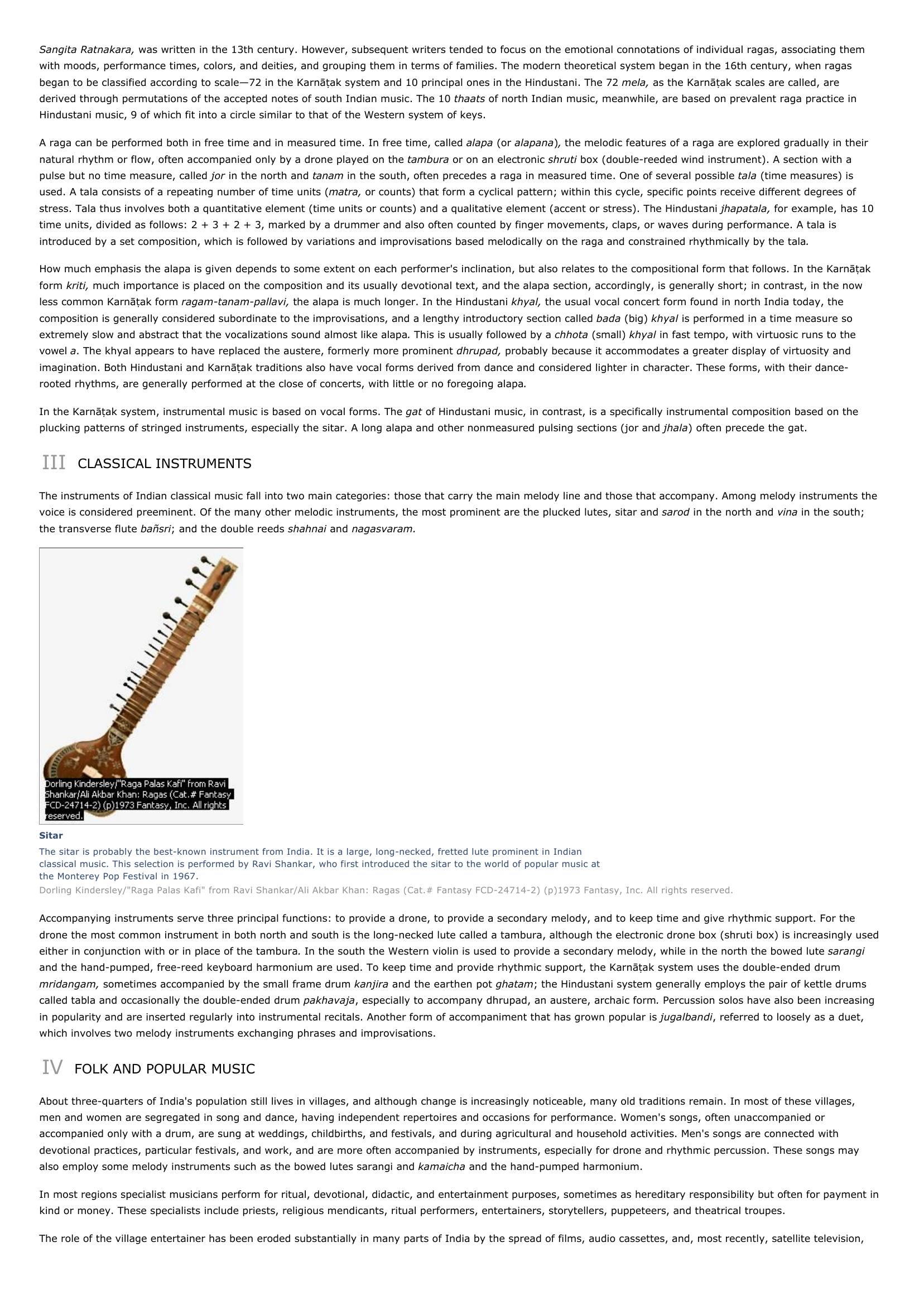

The instruments of Indian classical music fall into two main categories: those that carry the main melody line and those that accompany.

Among melody instruments thevoice is considered preeminent.

Of the many other melodic instruments, the most prominent are the plucked lutes, sitar and sarod in the north and vina in the south; the transverse flute bañsri ; and the double reeds shahnai and nagasvaram.

SitarThe sitar is probably the best-known instrument from India.

It is a large, long-necked, fretted lute prominent in Indianclassical music.

This selection is performed by Ravi Shankar, who first introduced the sitar to the world of popular music atthe Monterey Pop Festival in 1967.Dorling Kindersley/"Raga Palas Kafi" from Ravi Shankar/Ali Akbar Khan: Ragas (Cat.# Fantasy FCD-24714-2) (p)1973 Fantasy, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Accompanying instruments serve three principal functions: to provide a drone, to provide a secondary melody, and to keep time and give rhythmic support.

For thedrone the most common instrument in both north and south is the long-necked lute called a tambura, although the electronic drone box (shruti box) is increasingly usedeither in conjunction with or in place of the tambura .

In the south the Western violin is used to provide a secondary melody, while in the north the bowed lute sarangi and the hand-pumped, free-reed keyboard harmonium are used.

To keep time and provide rhythmic support, the Karn āṭak system uses the double-ended drummridangam, sometimes accompanied by the small frame drum kanjira and the earthen pot ghatam ; the Hindustani system generally employs the pair of kettle drums called tabla and occasionally the double-ended drum pakhavaja , especially to accompany dhrupad, an austere, archaic form .

Percussion solos have also been increasing in popularity and are inserted regularly into instrumental recitals.

Another form of accompaniment that has grown popular is jugalbandi , referred to loosely as a duet, which involves two melody instruments exchanging phrases and improvisations.

IV FOLK AND POPULAR MUSIC

About three-quarters of India's population still lives in villages, and although change is increasingly noticeable, many old traditions remain.

In most of these villages,men and women are segregated in song and dance, having independent repertoires and occasions for performance.

Women's songs, often unaccompanied oraccompanied only with a drum, are sung at weddings, childbirths, and festivals, and during agricultural and household activities.

Men's songs are connected withdevotional practices, particular festivals, and work, and are more often accompanied by instruments, especially for drone and rhythmic percussion.

These songs mayalso employ some melody instruments such as the bowed lutes sarangi and kamaicha and the hand-pumped harmonium.

In most regions specialist musicians perform for ritual, devotional, didactic, and entertainment purposes, sometimes as hereditary responsibility but often for payment inkind or money.

These specialists include priests, religious mendicants, ritual performers, entertainers, storytellers, puppeteers, and theatrical troupes.

The role of the village entertainer has been eroded substantially in many parts of India by the spread of films, audio cassettes, and, most recently, satellite television,.

»

↓↓↓ APERÇU DU DOCUMENT ↓↓↓

Liens utiles

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart I INTRODUCTION Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, an 18th-century Austrian classical composer and one of the most famous musicians of all time, came from a family of musicians that included his father and sister.

- William Faulkner I INTRODUCTION William Faulkner Twentieth-century American novelist William Faulkner wrote novels that explored the tensions between the old and the new in the American South.

- Mesopotamian Art and Architecture I INTRODUCTION Mesopotamian Art and Architecture, the arts and buildings of the ancient Middle Eastern civilizations that developed in the area (now Iraq) between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers from prehistory to the 6th century BC.

- Tragedy I INTRODUCTION Euripides Unlike other 5th-century BC Greek playwrights, tragic poet Euripides addressed the plight of the common people, rather than that of mythic heroes.

- Igor Stravinsky I INTRODUCTION Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971), Russian American composer, one of the most influential figures of music in the 20th century.