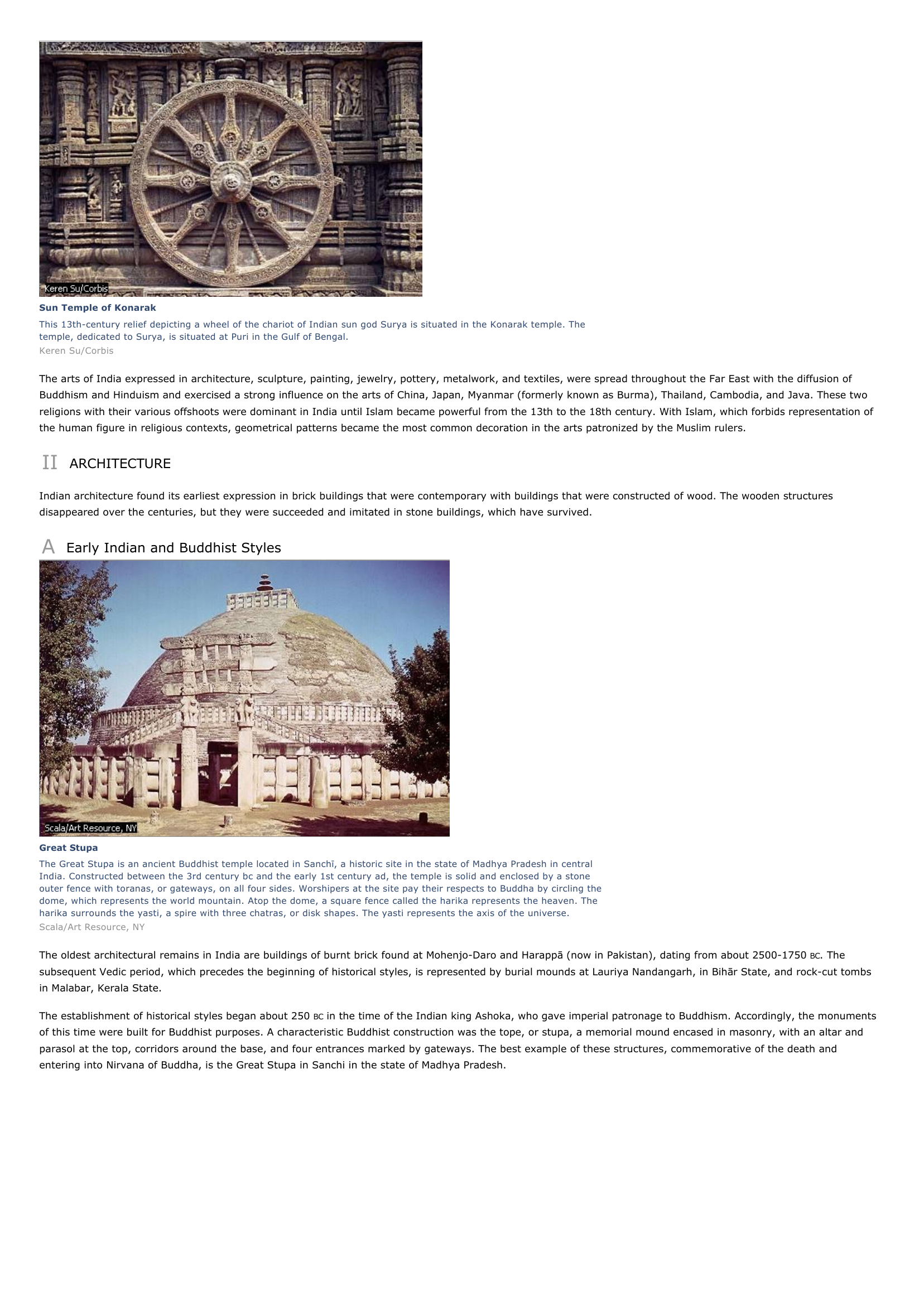

Indian Art and Architecture I INTRODUCTION Art on the Indian Subcontinent This map highlights places in India and Pakistan where prominent examples of Indian art and architecture have been produced. The sites include ? gra, location of the 17th-century domed mausoleum known as the Taj Mahal; Sanchi, site of the Great Stupa, an ancient Buddhist temple completed in the 1st century ad; Khajur? ho, where nearly 80 Hindu temples once stood; and Elephanta, known for its 8th-century temple caves containing statues of Hindu gods. Some of the oldest architectural remains, dating back to about 2500 bc, are located in Mohenjo-Daro and Harapp?, in Pakistan. © Microsoft Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Indian Art and Architecture, the art and architecture produced on the Indian subcontinent from about the 3rd millennium BC to modern times. To viewers schooled in the Western tradition Indian art may seem overly ornate and sensuous; appreciation of its refinement comes only gradually, as a rule. Voluptuous feeling is given unusually free expression in Indian culture. A strong sense of design is also characteristic of Indian art and can be observed in its modern as well as in its traditional forms. The art of India must be understood and judged in the context of the ideological, aesthetic, and ritual assumptions and needs of the Indian civilization. These assumptions were formed as early as the 1st century BC and have shown a remarkable tenacity through the ages. The Hindu-Buddhist-Jain view of the world is largely concerned with the resolution of the central paradox of all existence, which is that change and perfection, time and eternity, and immanence and transcendence operate dichotomously and integrally as parts of a single process. In such a situation the creation cannot be separated from the creator, and time can be comprehended only as a matrix of eternity. This conceptual view, when expressed in art, divides the universe of aesthetic experience into three distinct, although interrelated, elements--the senses, the emotions, and the spirit. These elements dictate the norms for architecture as an instrument of enclosing and transforming space and for sculpture in its volume, plasticity, modeling, composition, and aesthetic values. Instead of depicting the dichotomy between the flesh and the spirit, Indian art, through a deliberate sensuousness and voluptuousness, fuses one with the other through a complex symbolism that, for example, attempts to transform the fleshiness of a feminine form into a perennial mystery of sex and creativity, wherein the momentary spouse stands revealed as the eternal mother. Sri Lankan Decorated Casket The relief carving on this 16th-century casket from Sri Lanka depicts a nobleman riding an elephant as attendants and onlookers hail him. Another side of the casket is decorated with gold and rubies. Schatzkammer der Residenz, Munich/Werner Forman Archive The Indian artist deftly uses certain primeval motifs, such as the feminine figure, the tree, water, the lion, and the elephant. In a given composition, although the result is sometimes conceptually unsettling, the qualities of sensuous vitality, earthiness, muscular energy, and rhythmic movement remain unmistakable. The form of the Hindu temple; the contours of the bodies of the Hindu gods and goddesses; and the light, shade, composition, and volume in Indian painting are all used to glorify the mystery that resolves the conflict between life and death, time and eternity. Sun Temple of Konarak This 13th-century relief depicting a wheel of the chariot of Indian sun god Surya is situated in the Konarak temple. The temple, dedicated to Surya, is situated at Puri in the Gulf of Bengal. Keren Su/Corbis The arts of India expressed in architecture, sculpture, painting, jewelry, pottery, metalwork, and textiles, were spread throughout the Far East with the diffusion of Buddhism and Hinduism and exercised a strong influence on the arts of China, Japan, Myanmar (formerly known as Burma), Thailand, Cambodia, and Java. These two religions with their various offshoots were dominant in India until Islam became powerful from the 13th to the 18th century. With Islam, which forbids representation of the human figure in religious contexts, geometrical patterns became the most common decoration in the arts patronized by the Muslim rulers. II ARCHITECTURE Indian architecture found its earliest expression in brick buildings that were contemporary with buildings that were constructed of wood. The wooden structures disappeared over the centuries, but they were succeeded and imitated in stone buildings, which have survived. A Early Indian and Buddhist Styles Great Stupa The Great Stupa is an ancient Buddhist temple located in Sanch?, a historic site in the state of Madhya Pradesh in central India. Constructed between the 3rd century bc and the early 1st century ad, the temple is solid and enclosed by a stone outer fence with toranas, or gateways, on all four sides. Worshipers at the site pay their respects to Buddha by circling the dome, which represents the world mountain. Atop the dome, a square fence called the harika represents the heaven. The harika surrounds the yasti, a spire with three chatras, or disk shapes. The yasti represents the axis of the universe. Scala/Art Resource, NY The oldest architectural remains in India are buildings of burnt brick found at Mohenjo-Daro and Harapp? (now in Pakistan), dating from about 2500-1750 BC. The subsequent Vedic period, which precedes the beginning of historical styles, is represented by burial mounds at Lauriya Nandangarh, in Bih?r State, and rock-cut tombs in Malabar, Kerala State. The establishment of historical styles began about 250 BC in the time of the Indian king Ashoka, who gave imperial patronage to Buddhism. Accordingly, the monuments of this time were built for Buddhist purposes. A characteristic Buddhist construction was the tope, or stupa, a memorial mound encased in masonry, with an altar and parasol at the top, corridors around the base, and four entrances marked by gateways. The best example of these structures, commemorative of the death and entering into Nirvana of Buddha, is the Great Stupa in Sanchi in the state of Madhya Pradesh. Columns from Ajanta Caves, India Many Indian temples were supported by massive stone columns decorated with carved horizontal bands and richly sculpted capitals. This cave temple at Ajanta was carved between the 2nd century bc and the 7th century ad. Scala/Art Resource, NY Other Buddhist structures are the dagoba, a relic shrine, said to be the ancestral form of the pagoda; the lat, a stone edict pillar, generally monumental; the chaitya, a hall of worship in basilican form; and the vihara, a monastery or temple. Chaityas and viharas were often hewn out of living rock. Architectural details such as capitals and moldings show influence from Middle Eastern and Greek sources. Notable examples of early rock-cut monuments in Mah? r?shtra State are the Great Chaitya Hall at Karle (circa early 2nd century B AD ) with its elaborate sculptured facade and tunnel-vaulted nave, and various temples and monasteries at Ajanta and Ellora. Jain and Hindu Styles Temple of Devi Jogadanta The temple of Devi Jogadanta in Khajur? ho, India, exemplifies a style of architecture that flourished in north central India from the 10th to the 13th century. The features of the style include a longitudinal layout, rich sculptural decoration on both interior and exterior walls, and a central spire surrounded by clusters of secondary spires. Because of its remote location, the temple complex in Khajur? ho is better preserved than most Indian archaeological sites of comparable antiquity. Scala/Art Resource, NY Buddhism waned after the 5th century as Hinduism and Jainism became dominant. The Jain and Hindu styles overlapped and produced the elaborate allover patterns carved in bands that became the distinguishing feature of Indian architecture. The Jains often built on a gigantic scale, a marked feature being pointed domes constructed of level courses of corbeled stones. Extensive remains have been discovered on hilltops far removed from one another in three states, at Parasnath Hill in Bih?r, Mount Abut at Abu in R? jasth?n, and Satrunjaya in Gujar?t. Small temples were congregated in great numbers on hilltops; one of the earlier groups is on Mount ?bu. Typical of Jain commemorative towers is the richly ornamented, nine-story Jaya Sthamba. Orissan Temples The ancient city of Bhubaneshwar, in Orissa State, India, contains around 30 Orissan temples dating from the 6th to the 16th century. These temples display the characteristic emphasis on strong horizontal patterns and beehive-shaped towers crowned with a flat round stone. Robert Harding Picture Library The Hindu style is closely related to the Jain style. It is divided into three general categories: northern, from AD 600 to the present; central, from 1000 to 1300; and southern, or Dravidian, from 1350 to 1750. In all three periods the style is marked by great ornateness and the use of pyramidal roofs. Spirelike domes terminate in delicate finials. Other features include the elaborate, grand-scale gopuras, or gates, and the choultries, or ceremonial halls. Among the most famous examples of the style are the temples in the south at Belur, and at Halebid, Tiruvalur, Thanj?v? r, and Rameswaram in Tamil N?du State; temples in the north at Barolli in R?jasth?n, at V?r ?nasi in Uttar Pradesh, and at Konarak the Sun Temple in Orissa State. C Indo-Islamic Style Fatehpur Sikri The city of Fatehpur Sikri is located near ? gra, in northern India. Mughal emperor Akbar established the city as the capital of his empire in 1573, but 12 years later he abandoned it for unknown reasons. Fatehpur Sikri is now a popular tourist spot. Seen here is one of its several courtyards. © Microsoft Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Islamic architecture in India dates from the 13th century to the present. Brought to India by the first Muslim conquerors, Islamic architecture soon lost its original purity and borrowed such elements from Indian architecture as courtyards surrounded by colonnades, balconies supported by brackets, and above all, decoration. Islam, on the other hand, introduced to India the dome, the true arch, geometric motifs, mosaics, and minarets. Despite fundamental conceptual differences, Indian and Islamic architecture achieved a harmonious fusion, especially in certain regional styles. Indo-Islamic style is usually divided into three phases: the Pashtun, the Provincial, and the Mughal. Examples of the earlier Pashtun style in stone are at Ahmad?b ?d in Gujar?t State, and in brick at Gaur-Pandua in West Bengal State. These structures are closely allied to Hindu models, but are simpler and lack sculptures of human figures. The dome, the arch, and the minaret are constant features of the style; a famous monument in this style is the mausoleum Gol Gumbaz (17th century) in Bij? pur, Karn?taka State, which has a dome with a 43-m (142-ft) diameter, almost as big as that of Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome. Another notable structure is the fivestory stone and marble tower called the Qutb Minar (12th century), near Delhi. The Provincial style reflected the continued rebellion of the provinces against the imperial style of Delhi. The best example of this phase is in Gujar?t, where for almost two centuries until 1572, when Emperor Akbar finally conquered the region, the dynasties that succeeded one another erected many monuments in varying styles. The most notable structures in this phase are found in the capital, Ahmad? b? d. The Jami Masjid (1423) is unique in the whole of India; although Muslim in inspiration, the arrangement of 3 bays and almost 300 pillars, as well as the decoration, in this mosque is pure Hindu. Ibrahim Roza, Bij?pur Ibrahim Roza, located in Bij? pur, India, was constructed by Ibrahim Adil Shah II in the early 1600s for his queen, Taj Sultana. The minarets, or prayer towers, are 24 m (about 79 ft) high and may have inspired those of the Taj Mahal. Ibrahim Adil Shah and his family are buried here. Gian Berto Vanni/Corbis The Mughal phase of the Indo-Islamic style, from the 16th to the 18th century, developed to a high degree the use of such luxurious materials as marble. The culminating example of the style is the Taj Mahal in ?gra. This domed mausoleum of white marble inlaid with gemstones was built (1632-48) by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan as a tomb for his beloved wife. It stands on a platform set off by four slender minarets and is reflected in a shallow pool. Other famous examples of the Mughal style are the Pearl Mosque at ?gra, Uttar Pradesh State, the palace fortresses at ?gra and Delhi, and the great mosques at Delhi and Lahore (now in Pakistan). D Modern Styles Vidhana Soudha, Bangalore Located in Bangalore, in southern India, Vidhana Souda is considered one of the country's most spectacular buildings. Built in 1954 in neo-Dravidian style, the granite building houses the Karn? taka State Legislature and the secretariat. Charles and Josette Lenars/Corbis Building in India since the 18th century has either carried on the indigenous historical forms or has been patterned after European models introduced by the British. Numerous examples of Western styles of the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries may be seen in public buildings, factories, hotels, and houses. The most outstanding example of modern architecture in India is the city of Chand?garh, the joint capital of Hary?na and Punjab; the city was designed by the Swiss-born French architect Le Corbusier in collaboration with Indian architects. The broad layout of the city was completed in the early 1960s. Notable architectural features include the vaulted structure, topped by a huge, concrete roof umbrella, and the use of concrete grille and bright pastel colors in the Palace of Justice; the arrangement of concrete cubes topped by a concrete parasol that is the Governor's Palace; and the use of projections, recesses, stair towers, and other contrasting elements to break the monotony of the long facades of the secretariat building, which are 244 m (800 ft) long. Modern Indian architecture has incorporated Western styles, adapting them to local traditions and needs--as in the design of the railroad station at Alwar, R?jasth?n State. III SCULPTURE Descent of the Ganges, M?mallapuram A scene carved into rocks near M?mallapuram, India, depicts the descent of the sacred river Ganges from the Himalayas. Following a natural crack in the rock, the carving is 6 m (20 ft) high and depicts gods, celestial beings, and animals gathered along the river's path. The carvings date from the 7th century ad. Gian Berto Vanni/Corbis The earliest prehistoric sculpture in India was produced in stone, clay, ivory, copper, and gold. A Early Period Figure from Mohenjo-Daro Among the remains of the Mohenjo-Daro archaeological site in present-day Pakistan were terra-cotta, alabaster, and marble figures. This fragment shows a bearded male in ornamental dress dating from 3000 bc. Lancelot Link/Corbis Examples of the 3rd millennium BC from the Indus Valley, found among the remains of the burnt-brick buildings of Mohenjo-Daro, include alabaster and marble figures, terra-cotta figurines of nude goddesses, terra-cotta and faience representations of animals, a copper model of a cart, and numerous square seals of ivory and of faience showing animals and pictographs. The similarity of these objects to Mesopotamian work in subject matter and stylized form indicates an interrelationship of the two cultures and a possible common ancestry (see Mesopotamian Art and Architecture). In Vedic and later times, from the 2nd millennium to the 3rd century connections with Middle Eastern culture are not evident. An example of the earlier phase of this period is a 9th-century Nandangarh. Later, from 600 BC and religious symbols. B Buddhist Sculpture BC BC, gold figurine of a goddess, found at Lauriya to historical times, common examples include finely polished and ornamented stone disks and coins representing many kinds of animals Carvings on the Great Stupa Four gateways were built as entrances to the Great Stupa at Sanchi, India, during the 1st century bc. This detail of one of the gateways shows the intricate relief carvings of elephants, horses, camels, and human figures that decorate the gateways. Borromeo/Art Resource, NY With the rise of Buddhism in the 3rd century BC and the development of a monumental architecture in stone, stone sculpture both in relief and in the round became important architectural adjuncts. Buddha himself was not shown in early Indian art; he was represented by symbols and scenes from his life. Among other common subjects for representation were Buddhist deities and edifying legends. At this time and subsequently throughout the history of Indian sculpture, figures and ornamentation were arranged in intricately related compositions. Monuments of the period include the animal capitals of King Ashoka's sandstone edict pillars, and the marble railings that surround the Buddhist stupas at Bharhut, near Satna in Madhya Pradesh, where the reliefs seem to be compressed between the surface plane and the background plane. Also outstanding are the gates of the Great Stupa at Sanchi, where the reliefs suggest the delicacy and detail of ivory carving. In northwest India, in a region that was called Gandhara in ancient times and now includes Afghanistan and part of the Punjab, a Greco-Buddhist school of sculpture arose that combined the influence of Greek forms and Buddhist subject matter. It reached the peak of its production in the 2nd century AD. Although the Gandhara style greatly influenced sculptural work in Central Asia and even in China, Korea, and Japan, it did not have a major effect in the rest of India; it is probable, however, that the images as well as the symbols of Buddha developed at Gandhara later spread to Mathura, now in Uttar Pradesh, where an important school of sculpture developed from the 2nd century BC to the 6th century the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, AD. Remains of the earlier work of this school also show a close relationship to the style of the sculpture at Bharhut. Later, in the Mathura school discarded the old symbols of Buddha and represented him with actual figures. This innovation was carried on through subsequent phases of Indian sculpture. The Gupta period, from AD 320 to about 550, produced Buddhas with clearly defined lines and refined contours. The drapery of the figure was diaphanous and clung to the body as if wet. Often the figures were made on a great scale, as in the colossal copper sculpture, weighing about 1 metric ton, from Sultanganj, Bih?r State. C Hindu Sculpture Shiva The Hindu deity Shiva is shown here with three heads, each representing one of his divine aspects. This early 7th-century bust, right, stands over 5 m (18 ft) high. It is in a Hindu temple cut into a cave at Elephanta, India. Vanni/Art Resource, NY Hindu sculpture also developed during the Gupta period. Reliefs were carved in rock-cut sanctuaries in Udayagiri, Madhya Pradesh (400-600), and adorned temples at Garhwa, near Allah?b ?d, and Deogarh. From the 7th to the 9th century a number of schools flourished. They include the highly architectural style of the Pallavas, exemplified by the work at K?nchipuram, Tamil N?du; the Rastrakuta style, of which the best-preserved examples are a colossal temple relief and the three-headed bust of Shiva at Elephanta, near Mumbai (formerly Bombay); and the Kashm?r style, which shows some Greco-Buddhist influence in the remains at Vijrabror, and more indigenous forms in figures of Hindu gods found at Vantipor. Hindu Cave Temples This 8th-century rock-cut shrine dedicated to various Hindu gods is on Elephanta, an island off the coast of India. DPA/The Image Works From the 9th century to the consolidation of Muslim power at the beginning of the 13th century, Indian sculpture increasingly tended toward the linear, the forms appearing to be sharply outlined rather than voluminous. More so than previously, sculpture was applied as a decoration, subordinate to its architectural setting. It was intricate and elaborate in detail and was characterized by complicated, many-armed figures drawn from the pantheon of Hindu and Jain gods, which replaced the earlier simple figures of Buddhist gods. Emphasis on technical virtuosity also added to the multiplication of involved forms. Relief Sculpture in Khajur?ho, India These relief sculptures on a sandstone temple in Khajur? ho, India, date from the 11th century. They depict hundreds of figures in a variety of poses. Some poses are sexual in nature, while others are believed to be symbolic and have yet to be deciphered by archaeologists. Several sculpture-adorned temples devoted to Hinduism and Jainism are found in Khajur? ho, which is located in north central India. Robert Holmes/Corbis At this time the three distinct areas of production in sculpture were (1) the north and east, (2) Rajputana (now part of Gujar? t, Madhya Pradesh, and R?jasth?n states), and (3) the south-central and western regions. In the north and east, one of the main schools was centered in Bih?r and Bengal under the Pala dynasty from 750 to 1200. A notable source for sculpture was the monastery and university at Nalanda in Bih?r. Black slate was a common medium, and the themes, at first still Buddhist, gradually became more and more Hindu. Another northeastern school, in Orissa, produced typically Hindu work, including the monumental elephants and horses and erotic friezes at the Sun Temple in Konarak. In Rajputana the local style was exemplified in the hard sandstone temple of Khajur?ho, which was literally covered with Hindu sculptures. The south-central and western schools produced notable works at Mysore, Halebid, and Belur. The temples were embellished with friezes, pillars, and brackets carved in fine-grained dark stone. After the Muslims became dominant, they adopted many of the native patterns as ornament. The traditions have persisted until the present day, especially in the south, where art retains its indigenous purity. IV PAINTING Rajput Painting The Rajput style of northern Indian painting flourished from the 16th to the 19th century. Brightly colored and miniature, Rajput paintings resemble the illuminated manuscript paintings of the Mughal Empire. Most Rajput artists were Hindu, and their works depict scenes from daily life and stories from Hindu epics. In this 17th-century painting, Rajput princes hunt bears while an elephant and its rider rescue a fallen horseman from a tiger. Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Remains of Indian painting before from AD AD 100 have survived in two localities. The remarkable Buddhist murals in rock-cut shrines in Ajanta, in Mah?r?shtra, cover the period 50 to 642. The earlier paintings of the Ajanta caves represent figures of indigenous types, having noble bearing and depicted with strong sensuality. The painting in the Jogimara cave at Orissa belongs to two periods, 1st century BC and medieval; the later work is not as good, obscuring the earlier, more vigorous drawing. Krishna with His Maidens Krishna, shown with blue skin, is a human hero who is worshiped as an avatar, or earthly descent of the Hindu god Vishnu. This 17th-century painting, Krishna with His Maidens, is from the book Rasamanjari by Indian writer Bhanudatta. The flattened human figures appear in profile against a solid background. Fragments of iridescent beetle wings have been used in their jewelry. Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York The Gupta period established the classical phase of Indian art, at once serene and energetic, spiritual and voluptuous. Art was the explicit medium of stating spiritual conceptions. A special kind of painting, executed on scrolls, depicted the reward of good and evil deeds in the world. Painting of the Gupta period has been preserved in three of the Ajanta caves. Represented are numerous Buddhas, sleeping women, and love scenes. Another group of Buddhist wall paintings, found at Bamian, in Afghanistan, reveal that these artists could represent any human posture. The drawing is stated in firm outline, and the subjects vary from the sublime to the grotesque. The whole spirit is one of emphatic, passionate force. The paintings in the first and second Ajanta caves date from the early 7th century and can hardly be distinguished in style from those of the Gupta period. Represented are bacchanalian scenes of the type that recur in Buddhist art from the early Kusana period onward. Also of great interest are the Jain Palava paintings (7th century), discovered in a cave shrine at Sittan?vasal, Tamil N? du State. Remains of murals have been found at Ellora (late 8th century). Such subjects as a rider on a horned lion and many pairs of figures floating among clouds anticipate characteristic themes of the Indian medieval style. Akbar Visiting His Eastern Provinces Akbar, who ruled from 1556 to 1605, is generally considered the founder of India's Mughal Empire. This watercolor painting was created toward the end of his reign for a manuscript that told of his feats. In the painting Akbar and his entourage are traveling to the eastern parts of his empire. Akbar's Expedition by Boat to the Eastern Provinces (16021604) is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia Museum of Art/Corbis The only surviving documents of the Pala school are the illustrations in the two palm-leaf manuscripts in the University of Cambridge library, in England, one dating from the beginning and the other from the middle of the 11th century, and containing, in all, 51 miniatures. The illustrations represent Buddhist divinities or scenes from the life of Buddha, evidently replicas of traditional compositions. Radha and Krishna in the Grove Many Indian paintings depict the love of the married woman Radha for the Hindu god Krishna. Their love affair symbolizes the human longing for union with the divine. In this colorful painting, the natural world around the lovers appears to spring to life and reflect their joyous embrace. This painting, which dates from 1780, is in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, England. Victoria & Albert Museum, London, UK/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York One example of an illustrated Kalpa Sutra, or manual of religious ceremonial, on palm leaf is known, dated equivalent to 1237 and now at Patan, Gujar?t. The variety of scenes represented affords valuable information on the manners, customs, and dress of the Guj?r?ti culture; Guj?r?ti painting was a continuation of the early western Indian style; the frescoes of Ellora represent an intermediate stage of development. Churning of the Sea This Indian miniature painting (15th century to 17th century) depicting the churning of the sea represents the cosmic struggle between order and chaos. The Hindu Devas, or deities who rule the heaven, air, and earth, are opposed by the demonic Asuras. The high gods have wrapped a serpent around Mount Mandara and set it in the ocean where the Devas and the Asuras, pulling on the snake, churn the ocean into butter. Giraudon/Art Resource, NY Rajput painting flourished in Rajputana, Bundelkhand (now part of Madhya Pradesh), and the Punjab Himalayas from the late 16th into the 19th century. It consisted of manuscript illumination in flat, decorative patterns and bright colors that resembled Persian and Mughal painting of the same period. Rajput painting, a refined and lyrical folk art, illustrates traditional Hindu epics, especially the life of the god Krishna. The Ten Incarnations of Vishnu The Hindu god Vishnu appears on Earth in ten incarnations, called avatars, to destroy injustice and save humankind. Sacred Hindu writings called the Puranas describe these incarnations. Vishnu is always depicted in dark blue or black and usually with four arms, though his avatars may take other forms, such as the golden fish (top left panel) and the man lion (panel below the fish). In his tenth avatar, still to come, Vishnu will appear with a white horse (bottom right panel) to destroy the universe. This painting was created about 1890 in Jaipur in northern India and is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, England. Victoria and Albert Museum Mughal painting, derived from the sophisticated Persian tradition, was a court art sponsored by the emperors. Reflecting an exclusive interest in secular life, it is essentially an art of portraiture and of historical chronicle. Mughal painting, on manuscripts or as independent album leaves, is dramatic and precisely realistic in detail, showing Western influence. Painters signed their own work, and at least 100 of their names are known. Caliph Uthman ibn Affan Uthman ibn Affan was appointed the third caliph (spiritual and secular leader) of Islam in 644. In this Indian manuscript painting from the late 18th century, he is shown seated with prayer beads in his hand and a copy of the Qur'an, the sacred scripture of Islam, on a stand. During his caliphate, a standardized version of the Qur'an was achieved. This miniature painting in gouache, from the Deccan school, is in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Victoria & Albert Museum, London /Art Resource, NY By the end of the 19th century, traditional Indian painting had begun to die out, replaced by work merely imitative of Western styles; European influence had started to infiltrate with the establishment of British rule in India. After the turn of the century there was a revival of interest in the older styles (stimulated by the archaeological study that had been going on in India since about the middle of the 19th century). Art centers arose in Bombay and, more importantly, in Bengal, where many of the artists were associated with the Calcutta (now Kolkata) School of Art and with Visva-Bharati, the university founded in 1921 by the Indian poet and painter Rabindranath Tagore to reconcile Indian and Western traditions. Experiments were made in styles ranging from Ajanta, Rajput, and Mughal painting to impressionism, postimpressionism, and surrealism. Artists such as Nandalal Bose drew their inspiration primarily from Ajanta art; others, like Jamini Roy, found their inspiration in Bengali folk art. By the mid-20th century, Indian painting was international in flavor, and Indian artists were working in a number of different idioms. V JEWELRY, POTTERY AND TEXTILES Indian Necklaces These three necklaces from India are examples of fine workmanship. The necklace with the seven separate pieces is known as a satratana; each of its jewels represents a planet within the Indian astrological system. The enameled cloisonné gold sections are strung together with emerald beads. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Of all the decorative arts in India, jewelry is the most universally interesting and beautiful. The techniques of filigree and granular work, which disappeared in Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire and were not used again until their introduction by the Moors in the 15th century, were never lost in India. Indian Jewelry Jewelry is a fine example of the high quality of decorative arts in India. A ringlike paizeb, left, is set with diamonds and gold. A khanjar, or ornamental dagger, right, is set with diamonds, gems, and gold. Both pieces date from the 19th century. Christie's Images The special qualities that distinguish the best Indian pottery are the strict subordination of color and ornament to form, and the conventionalizing and repetition of natural forms in the decoration. Unglazed pottery has been made throughout India; decorative pottery for commercial purposes, painted, gilded, and glazed, is made in special varieties in different provinces. Exquisite color tones and combinations are found in the glazed tiles that came into fashion with the Muslim conquest after the 11th century. Among the branches of artistic metalwork, that of the arms and equipment of the great chieftains is prominent. Kashm?r is noted for its richly colored woolen shawls; Surat, in Gujar?t, is known for silk prints; and sumptuous brocades come from Ahmad?b ?d and V?r ?nasi, and from Murshid?b ?d in western Bengal. India has long been famous for its silk and cotton textiles, printed and embroidered as well as loom figured. Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.