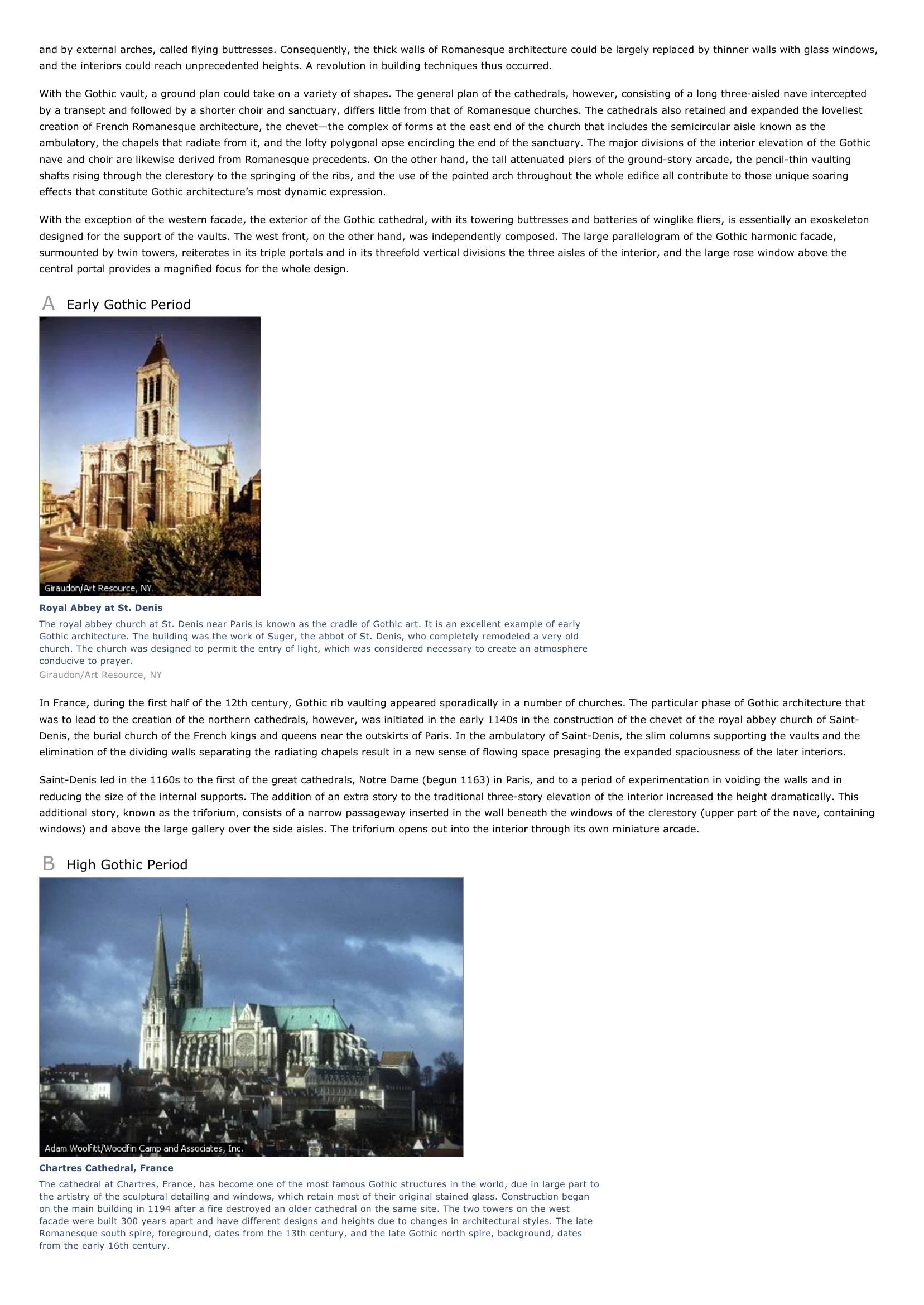

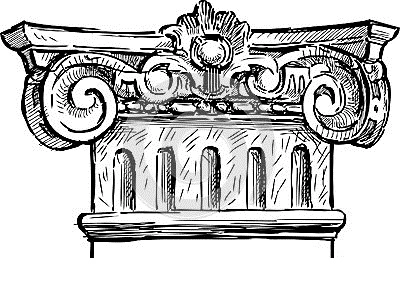

Gothic Art and Architecture I INTRODUCTION Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris Notre Dame Cathedral, in Paris, was begun in 1163 and completed for the most part in 1250. It is one of the best-known Gothic cathedrals in the world. The view here is of the south side, overlooking the Seine River, displaying the dramatic flying buttresses and one of the famous rose windows. Although Notre Dame is considered a Gothic structure, it incorporates remnants of the earlier Romanesque style. Giraudon/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Gothic Art and Architecture, religious and secular buildings, sculpture, stained glass, and illuminated manuscripts and other decorative arts produced in Europe during the latter part of the Middle Ages (5th century to 15th century). Gothic art began to be produced in France about 1140, spreading to the rest of Europe during the following century. The Gothic Age ended with the advent of the Renaissance in Italy about the beginning of the 15th century, although Gothic art and architecture continued in the rest of Europe through most of the 15th century, and in some regions of northern Europe into the 16th century. Originally the word Gothic was used by Italian Renaissance writers as a derogatory term for all art and architecture of the Middle Ages, which they regarded as comparable to the works of barbarian Goths. Since then the term Gothic has been restricted to the last major medieval period, immediately following the Romanesque (see Romanesque Art and Architecture). The Gothic Age is now considered one of Europe's outstanding artistic eras. II ARCHITECTURE Flying Buttresses, Bourges Cathedral Flying buttresses--arched supports on the exterior of Gothic cathedrals--provide a counterthrust to the outward pressure exerted on the high walls by the vaulted stone ceilings. The Cathedral of St Étienne in Bourges, shown here, is one of the most beautiful examples of Gothic architecture in France. It was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1992. Michel Langrognet Architecture was the dominant expression of the Gothic Age. Emerging in the first half of the 12th century from Romanesque antecedents, Gothic architecture continued well into the 16th century in northern Europe, long after the other arts had embraced the Renaissance. Although a vast number of secular monuments were built in the Gothic style, it was in the service of the church, the most prolific builder of the Middle Ages, that the new architecture evolved and attained its fullest realization. The aesthetic qualities of Gothic architecture depend on a structural development: the ribbed vault (see Arch and Vault). Medieval churches had solid stone vaults (the structure that supports the ceiling or roof). These were extremely heavy structures and tended to push the walls outward, which could lead to the collapse of the building. In turn, walls had to be heavy and thick enough to bear the weight of the stone vaults. Early in the 12th century, masons developed the ribbed vault, which consists of thin arches of stone, running diagonally, transversely, and longitudinally. The new vault, which was thinner, lighter, and more versatile, allowed a number of architectural developments to take place. Although the earliest Gothic churches assumed a wide variety of forms, the creation of a series of large cathedrals in northern France, beginning in the second half of the 12th century, took full advantage of the new Gothic vault. The architects of the cathedrals found that, since the outward thrusts of the vaults were concentrated in the small areas at the springing of the ribs and were also deflected downward by the pointed arches, the pressure could be counteracted readily by narrow buttresses and by external arches, called flying buttresses. Consequently, the thick walls of Romanesque architecture could be largely replaced by thinner walls with glass windows, and the interiors could reach unprecedented heights. A revolution in building techniques thus occurred. With the Gothic vault, a ground plan could take on a variety of shapes. The general plan of the cathedrals, however, consisting of a long three-aisled nave intercepted by a transept and followed by a shorter choir and sanctuary, differs little from that of Romanesque churches. The cathedrals also retained and expanded the loveliest creation of French Romanesque architecture, the chevet--the complex of forms at the east end of the church that includes the semicircular aisle known as the ambulatory, the chapels that radiate from it, and the lofty polygonal apse encircling the end of the sanctuary. The major divisions of the interior elevation of the Gothic nave and choir are likewise derived from Romanesque precedents. On the other hand, the tall attenuated piers of the ground-story arcade, the pencil-thin vaulting shafts rising through the clerestory to the springing of the ribs, and the use of the pointed arch throughout the whole edifice all contribute to those unique soaring effects that constitute Gothic architecture's most dynamic expression. With the exception of the western facade, the exterior of the Gothic cathedral, with its towering buttresses and batteries of winglike fliers, is essentially an exoskeleton designed for the support of the vaults. The west front, on the other hand, was independently composed. The large parallelogram of the Gothic harmonic facade, surmounted by twin towers, reiterates in its triple portals and in its threefold vertical divisions the three aisles of the interior, and the large rose window above the central portal provides a magnified focus for the whole design. A Early Gothic Period Royal Abbey at St. Denis The royal abbey church at St. Denis near Paris is known as the cradle of Gothic art. It is an excellent example of early Gothic architecture. The building was the work of Suger, the abbot of St. Denis, who completely remodeled a very old church. The church was designed to permit the entry of light, which was considered necessary to create an atmosphere conducive to prayer. Giraudon/Art Resource, NY In France, during the first half of the 12th century, Gothic rib vaulting appeared sporadically in a number of churches. The particular phase of Gothic architecture that was to lead to the creation of the northern cathedrals, however, was initiated in the early 1140s in the construction of the chevet of the royal abbey church of SaintDenis, the burial church of the French kings and queens near the outskirts of Paris. In the ambulatory of Saint-Denis, the slim columns supporting the vaults and the elimination of the dividing walls separating the radiating chapels result in a new sense of flowing space presaging the expanded spaciousness of the later interiors. Saint-Denis led in the 1160s to the first of the great cathedrals, Notre Dame (begun 1163) in Paris, and to a period of experimentation in voiding the walls and in reducing the size of the internal supports. The addition of an extra story to the traditional three-story elevation of the interior increased the height dramatically. This additional story, known as the triforium, consists of a narrow passageway inserted in the wall beneath the windows of the clerestory (upper part of the nave, containing windows) and above the large gallery over the side aisles. The triforium opens out into the interior through its own miniature arcade. B High Gothic Period Chartres Cathedral, France The cathedral at Chartres, France, has become one of the most famous Gothic structures in the world, due in large part to the artistry of the sculptural detailing and windows, which retain most of their original stained glass. Construction began on the main building in 1194 after a fire destroyed an older cathedral on the same site. The two towers on the west facade were built 300 years apart and have different designs and heights due to changes in architectural styles. The late Romanesque south spire, foreground, dates from the 13th century, and the late Gothic north spire, background, dates from the early 16th century. Adam Woolfitt/Woodfin Camp and Associates, Inc. The complexities and experiments of this early Gothic period were finally resolved in the new cathedral of Chartres (begun 1194). By omitting the second-story gallery derived from Romanesque churches but retaining the triforium, a simplified three-story elevation was reestablished. Additional height was now gained by means of a lofty clerestory that was almost as high as the ground-story arcade. The clerestory itself was now lighted in each bay or division by two very tall lancet windows surmounted by a rose window. At one stroke the architect of Chartres established the major divisions of the interior that were to become standard in all later Gothic churches. Reims Cathedral, France This cathedral in Reims, France, represents the peak of the High Gothic architectural style. Built between 1211 and 1300, the church was used for coronations of the French monarchy. The cathedral exhibits characteristically Gothic attributes such as three-tier elevation, three-part vaults, shafted piers, flying buttresses, and gargoyles. This is a view of the west facade, which features the first examples of bar tracery in its large rose window. Scope The High Gothic period, inaugurated at Chartres, culminates in the Cathedral of Reims (begun 1210). Rather cold and overpowering in its perfectly balanced proportions, Reims represents the classical moment of serenity and repose in the evolution of the Gothic cathedrals. Bar tracery, that characteristic feature of later Gothic architecture, was an invention of the first architect of Reims. In the earlier plate tracery, as in the clerestory at Chartres, a solid masonry wall is pierced by a series of openings. In bar tracery, however, a single window is subdivided into two or more lancets by means of long thin monoliths, known as mullions. The head of the window is filled with a tracery design that has the effect of a cutout. Facade of Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris The Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris is a splendid example of Gothic architecture. The facade of the cathedral, built from 1190 to 1240, is characterized by its two imposing towers. The entrance doors are set into pointed arches finely decorated with sculpture depicting the Last Judgment, Saint Anne, and the Coronation of the Virgin. Above the doors is a row of statues of angels and saints surmounted by windows and a colonnade. The large, central rose window has multicolored glass panes. SIME/Morandi Bruno/4Corners Images Reims follows the general scheme of Chartres. But another equally successful High Gothic solution to the problems of interior design occurs in the great five-aisled cathedral at Bourges (begun 1195). Instead of an enlarged clerestory, as at Chartres, the architect of Bourges created an immensely tall ground-story arcade and reduced the height of the clerestory to that of the triforium. The brief interval of the High Gothic period is followed in the 1220s by the nave of Amiens Cathedral. The soaring effects, muted at Chartres and Reims, were taken up again at Amiens in the emphasis on verticality and in the attenuation of the supports. Amiens thus provided a transition to the loftiest of the French Gothic cathedrals, that of Beauvais. By superimposing on a giant ground-story arcade (derived from Bourges) an almost equally tall clerestory, the architect of Beauvais reached the unprecedented interior height of 48 m (157 ft). C Rayonnant Gothic Period Rose Window, Notre Dame The north rose window of the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris (1240-1250) was built by Jean de Chelles. It is designed in the Rayonnant style, named for the radiating spokes in this type of window. The center circle depicts the Virgin and Child, surrounded by figures of prophets. The second circle shows 32 Old Testament kings, and the outer circle depicts 32 high priests and patriarchs. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Beauvais was begun in 1225, the year before Louis IX, king of France, ascended the throne. During his long reign, from 1226 to 1270, Gothic architecture entered a new phase, known as the Rayonnant. The word Rayonnant is derived from the radiating spokes, like those of a wheel, of the enormous rose windows that are one of the features of the style. Height was no longer the prime objective. Rather, the architects further reduced the masonry frame of the churches, expanded the window areas, and replaced the external wall of the triforium with traceried glass. Instead of the massive effects of the High Gothic cathedrals, both the interior and the exterior of the typical Rayonnant church now more nearly assumed the character of a diaphanous shell. All these features of the Rayonnant were incorporated in the first major undertaking in the new style, the rebuilding (begun 1232) of the royal abbey church of SaintDenis. Of the earlier structure only the ambulatory and the west facade were preserved. The spirit of the Rayonnant, however, is perhaps best represented by the Sainte-Chapelle, the spacious palace chapel built by Louis IX on the Île de la Cité in the center of Paris. Construction began in the early 1240s, and the chapel was consecrated in 1248. Immense windows, rising from near the pavement to the arches of the vaults, occupy the entire area between the vaulting shafts, thus transforming the whole chapel into a sturdy stone armature for the radiant stained-glass windows. In the evolution of Gothic architecture, the progressive enlargement of the windows was not intended to shed more light into the interiors, but rather to provide an ever-increasing area for the stained glass. As can still be appreciated in the Sainte-Chapelle and in the cathedrals of Chartres and Bourges, Gothic interiors with their full complement of stained glass were as dark as those of Romanesque churches. It was, however, a luminous darkness, vibrant with the radiance of the windows. The dominant colors were a dark saturated blue and a brilliant ruby red. Small stained-glass medallions illustrating episodes from the Bible and from the lives of the saints were reserved for the windows of the chapels and the side aisles. Their closeness to the observer made their details easily distinguishable. Each of the lofty windows of the clerestory, on the other hand, was occupied by single monumental figures. Because of their often colossal size, they were also readily visible from below. Beginning in the 1270s the mystic darkness was gradually dispelled as grisaille glass--white glass decorated with designs in gray--was more often employed in conjunction with colored panels, while the colors themselves grew progressively lighter in tone. D Dissemination of Gothic Architecture Cologne Cathedral Cologne Cathedral has two massive spires which overlook the Rhine River in Cologne, Germany. Begun in 1248, the cathedral is the largest Gothic structure in the world. This photo shows the ornately carved south transept-portal of the building. Ruggero Vanni/Corbis The influence of French Gothic architecture on much of the rest of Europe was profound. In France the scheme of Bourges, with its giant arcade and short clerestory, met with little response, but in Spain it was taken up again and again, beginning in 1221 with the Cathedral of Toledo and continuing into the early 14th century with the cathedrals of Palma de Mallorca, Barcelona, and Gerona. In Germany the impact of all phases of French Gothic architecture was decisive, from the early Gothic fourstory elevation of the Cathedral of Limburg-an-der-Lahn (1225?) to the choir of Cologne Cathedral (begun 1248). Modeled on the Rayonnant choir of Amiens, the interior of Cologne exceeds in height even that of Beauvais. Italy and England, however, are the exceptions to this pervasive French influence. The peculiarly Italianate idiom of the Gothic churches of Florence and the superficial reminiscences of the French Gothic facades on the cathedrals of Siena and Orvieto are but transitory phases in a development that leads from the Italian Romanesque to Filippo Brunelleschi and the beginnings of the Renaissance. Salisbury Cathedral Salisbury Cathedral in Salisbury, England, is an example of English Gothic architecture. It was built between 1220 and 1260, but the crossing tower, flying buttresses, and spire were added in the 14th century. The two sets of transepts on the north and east sides are unusual for Gothic buildings, as is the pastoral setting. John Bethell/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York In England, French Gothic architecture intruded itself only twice, once in the 1170s in the eastern extension of Canterbury Cathedral and again in Henry III's Westminster Abbey (begun 1245), patterned on the general scheme of Reims, with Parisian Rayonnant modifications. Otherwise the English architects developed their own highly successful Gothic idiom. Rejecting the aspiring verticality and the functional logic of the French cathedrals, the English churches emphasize length and horizontality, replacing the French polygonal apse with a square east end that is sometimes further prolonged by a rectangular Lady chapel (a chapel devoted to the Virgin Mary, characteristic of English cathedrals). This extreme elongation often includes two separate transepts. The multiplication in the number of ribs, some of which are of a purely ornamental nature, is also characteristically English. Orvieto Cathedral, Italy The historic town of Orvieto is situated on a hilltop in the Umbria region of central Italy. The best-known monument in the city is the cathedral, which was begun in 1290 in the Romanesque style but completed later in the Gothic style. Stone reliefs and mosaics decorate the Gothic facade. Scala/Art Resource, NY The first major phase of this insular architecture, the early English period, is well represented (except for the 15th-century tower and spire) by the Cathedral of Salisbury (begun 1220). The introduction of bar tracery in Westminster Abbey led to an astonishing variety in tracery design. This Decorated period, with its lavish ornamentation, also produced such poetic creations as the lovely Angel Choir (begun 1256) of Lincoln Cathedral, and was responsible as well for that unique masterpiece of medieval architecture, the astounding octagon (begun 1322) of Ely Cathedral, with its wooden lantern and tower soaring over the crossing. III SCULPTURE Sculpture Timeline Try your knowledge of sculpture through the ages with this interactive timeline. Use your mouse to drag the sculptures to the periods in which they were created. To learn about each sculpture, hover your mouse over an image after placing it correctly in the timeline. © Microsoft Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Following a Romanesque precedent, a multitude of carved figures proclaiming the dogmas and beliefs of the church adorn the vast cavernous portals of French Gothic cathedrals. Gothic sculpture in the 12th and early 13th centuries was predominantly architectural in character. The largest and most important of the figures are the over-life-size statues in the embrasures on either side of the doorways. Because they are attached to the colonnettes by which they are supported, they are known as statue-columns. Eventually the statue-column was to lead to the freestanding monumental statue, a form of art unknown in western Europe since Roman times. Statue-Columns at Chartres Cathedral These representations of saints, found on the columns around the north transept of the cathedral at Chartres, France, were built between 1132 and 1240. Although the style is still influenced by Romanesque art, it is more naturalistic, with the statue-columns more three-dimensional and less tied to the wall behind them than sculpture had been in earlier architecture. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York The earliest surviving statue-columns are those of the west portals of Chartres that stem from the older pre-Gothic cathedral and that date from about 1155. The tall, cylindrical figures repeat the form of the colonnettes to which they are bound. They are rendered in a severe, linear Romanesque style that nevertheless lends to the figures an impressive air of aspiring spirituality. During the next few decades the west portals of Chartres inspired a number of other French portals with statuecolumns. They were also influential in the creation of that sculptural ensemble on the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, fittingly known as the Portico de la Gloria (completed 1188), one of the outstanding artistic achievements of medieval Spain. Facade of Burgos Cathedral, Spain Christ in Majesty, holding the Book of the Law, is depicted on the sculptural panel over the main portal of Burgos Cathedral in Spain. He is surrounded by the symbols of the four evangelists--Matthew (Human), Mark (Lion), Luke (Ox), and John (Eagle). The evangelists are also shown seated at desks, writing their gospels. The figures provide an excellent example of Gothic sculpture in Spain. Ángeles Jiménez All these proto-Gothic monuments, however, still retain a distinct Romanesque character. In the 1180s the Romanesque stylization gives way to a period of transition in which the statue begins to assume a feeling of grace, sinuosity, and freedom of movement. This so-called classicizing style culminates in the first decade of the 13th century in the great series of sculptures on the north and south transept portals of Chartres. The term classicizing, however, must be qualified, for a fundamental difference exists between the Gothic figure of any period and the truly classical figure style. In the classical figure, whether statue or relief, a completely articulated body can be sensed beneath, and separate from, the drapery. In the Gothic figure no such differentiation exists. What can be discerned of the body is inseparable from the folds of the garment by which it is enveloped. Even where the nude is portrayed, as in the statues of Adam and Eve (before 1237) on the German Cathedral of Bamberg, the body is largely reduced to an abstraction. A Emergence of Naturalism Virgin of Jeanne d'Evreux French Gothic artists became increasingly interested in realism during the early 14th century. This gilded silver statue, created around 1330, illustrates the Virgin Mary in a naturalistic pose, holding the infant Jesus Christ as he reaches out to touch her face. It is in the Louvre in Paris, France. Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY Beginning about 1210 on the Coronation Portal of Nôtre Dame and continuing after 1225 on the west portals of Amiens Cathedral, the rippling surface treatment of the classicizing drapery was replaced by more solid volumes. In the 1240s, on the west facade of Reims and in the statues of the apostles in the Sainte-Chapelle, the drapery assumes those sharp, angular forms and deeply carved tubular folds that are characteristic of almost all later Gothic sculpture. At the same time the statues are finally liberated from their architectural bondage. Sculpture of the Archangel Gabriel This sculpture of the archangel Gabriel appears opposite the Virgin Mary on the western entrance to the cathedral of Notre-Dame at Reims, France. Gabriel is the angel who brings Mary the news that she is to bear the son of God. Earlier depictions of the Annunciation had presented it as a solemn occasion, but this statue of a smiling angel from the second half of the 13th century injects a note of gaity. Paul Almasy/Corbis In the statues at Reims and in the interior of the Sainte-Chapelle, the exaggerated smile, almond-shaped eyes, and clustered curls of the small heads and the mannered poses result in a paradoxical synthesis of naturalistic forms, courtly affectations, and a delicate spirituality. Along with these manneristic tendencies and the increased naturalism, a more maternal type of the cult statue of the Virgin Mary playfully balancing the Christ child on the outward thrust of her hip made its first appearance on the lower portal of the Sainte-Chapelle--an image that in the ensuing centuries was disseminated in infinite variations throughout Europe. B Diffusion of Gothic Sculpture Bamberg Rider Attached to a pier in the Bamberg Cathedral in Germany, the Bamberg Rider stands as a notable achievement of German Gothic sculpture. Made in 1240, the Bamberg Rider is one of the first examples of freestanding, independent sculpture in Europe--until then most sculptures were dependent on their specific architectural setting. Many historians believe the sculpture's horseman represents Conrad III, king of Germany from 1138 to 1152. Scala/Art Resource, NY Although northern France was the creative heartland of Gothic sculpture, as it was of Gothic architecture, some of the outstanding sculptural monuments were produced in Germany. Expanding on the French Gothic style, German Gothic sculpture ranges from an expressionistic exaggeration, sometimes verging on caricature, to a lyrical beauty and nobility of the forms. The largest assemblage of German 13th-century sculpture, that of the Cathedral of Bamberg, created under the influence of Reims, culminated about 1240 in the Bamberg Rider, the first equestrian statue in Western art since the 6th century. Although the identity of the regal horseman remains unknown, no other work so impressively embodies the heroic ideal of medieval kingship. The influence of French Gothic sculpture in Italy was, like the architecture, more superficial and transitory than in Germany. This influence can indeed be aptly described as Gothicizing trends in the larger framework of the Italian proto-Renaissance that in sculpture began in 1260 with Nicola Pisano's marble pulpit in the Pisa Baptistry. Giovanni Pisano, the son of Nicola, was the first to adopt the full repertory of French Gothic mannerisms. Of great inner intensity and power, the statues of prophets and Greek philosophers he created about 1290 for the facade of the Cathedral of Siena are also the masterpieces of this entire Italian period. Although during the later decades of the 14th century an ever-increasing number of Italian sculptors assumed the French Gothic mannerisms, again and again their works show the study of the classical nude and differentiate between body and drapery in a way that is the mark of the classical style. This Gothicizing phase had ended about 1400 with the advent of Lorenzo Ghiberti in Florence and the beginnings in sculpture of the full Italian Renaissance. IV DECORATIVE ARTS Reliquary Shrine During the 13th century, many artisans created elaborately detailed reliquary shrines dedicated to saints. This example, in the shape of a miniature church, is dedicated to Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, and is located in Marburg, Germany. Foto Marburg/Art Resource, NY In France throughout the 13th century the decorative arts were largely dominated by church art. The medallions that form the illustrations in the Bibles moralisées (Moralized Bibles) of the second quarter of the century frankly emulate the designs of stained glass. In Louis IX's Psalter (composed after 1255), the gables with rose windows that frame the miniatures were patterned after the ornamental gables surmounting the exterior of the Sainte-Chapelle. Beginning about 1250 the same courtly style informs both monumental statues and small ivory figurines. The elegant ivory statuette of the Virgin Mary and Child (1265?, Louvre, Paris) from the SainteChapelle was modeled after the monumental statue from the chapel's lower portal. The colossal group of Christ crowning the Virgin Mary in the central gable of the west facade of Reims possesses all the intimate grace of the same subject depicted in two contemporary statuettes, also in the Louvre. Beginning in the 1260s the large metal reliquary shrines take the form of diminutive Rayonnant churches, complete with transepts, rose windows, and gabled facades (see Metalwork). About 1300 the decorative arts begin to assume a more independent role. In the Rhineland, German expressionism gave rise to works of a marked emotional character, ranging from the statuettes of the school of Bodensee, such as that of the youthful seated Saint John tenderly laying his head on the shoulder of Christ, to the harrowing evocation of the suffering Christ in the plague crosses of the Middle Rhine. Later in the century the German sculptors were responsible for a new type of the mourning Virgin Mary, seated and holding on her lap the dead body of Christ, the so-called Pietà. In the second quarter of the century, Parisian manuscript illumination was given a new direction by Jean Pucelle. In his Belleville Breviary (1325?, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris), the lettering, the illustrations, and the leafy borders all contribute to the totally integrated effect of the decorated page, thereby establishing an enduring precedent for later illuminators. Of still greater significance for future developments is the new sense of space imparted to the interior scenes in his illustrations through the use of linear perspective. Pucelle had learned this technique from the contemporary painters of the Italian proto-Renaissance (see Illuminated Manuscripts). V LATE GOTHIC PERIOD Paris had been the leading artistic center of northern Europe since the 1230s. After the ravages of the Plague and the outbreak of the Hundred Years' War in the 1350s, however, Paris became only one among many artistic centers. A Painting Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (January) Flemish artists illustrated the medieval manuscript known as the Très riches heures for the duke de Berry of Burgundy. Each month has its own illustration. Shown here is a feast during the month of January, a time of giving gifts. Victoria & Albert Museum, London/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York As a result of this diffusion of artistic currents, a new pictorial synthesis emerged, known as the International Gothic style, in which, as foreshadowed by Pucelle, Gothic elements were combined with the illusionistic art of the Italian painters. Beginning in Paris in the 1370s and continuing until about 1400 at the court of Jean de France, Duc de Berry, the manuscript illuminators of the International Gothic style progressively developed the spatial dimensions of their illustrations, until the picture became a veritable window opening on an actual world. This process led eventually to the realistic painting of Jan van Eyck and the northern Renaissance and away from the conceptual point of view of the Middle Ages. Thus, even though the International style is sometimes described as Gothic, it nevertheless lies beyond the boundaries of the Gothic period itself, which by definition is also medieval. B Sculpture Portion of The Well of Moses The Well of Moses (1395-1403) was a monument created by the Dutch sculptor Claus Sluter for the Carthusian monastery Chartreuse de Champmol in Dijon, France. The base of the monument is all that remains intact today; the portion seen here shows the prophets Daniel and Isaiah in dispute. The figures are life-size, and were originally painted in bright colors. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Gothic sculpture, however, remained unaffected by the Italian proto-Renaissance. About 1400 Claus Sluter executed at Dijon for Philip the Bold, Duke of Bourgogne, some of the most memorable sculptural works of the late Gothic period. Eschewing the slender willowy figure style and aristocratic affectations of the 14th century, Sluter enveloped his figures in vast voluminous robes. In the mourners on the tomb (begun 1385, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon) of Philip the Bold, Sluter created out of drapery alone eloquent images of sorrow. In the statues surrounding the Well of Moses (1395-1403, Chartreuse de Champmol, Dijon) he transformed the Old Testament heroes into earthy Flemish patriarchs, whose realistic depiction nevertheless conveys a feeling of spiritual grandeur. Altarpiece by Veit Stoss One of the finest works of German sculptor Veit Stoss is the dramatic wooden altarpiece he created for the Church of Saint Mary in Kraków, Poland. The central panel shows the death and assumption of the Virgin Mary, and scenes in the side panels recall the main events in her life. This late Gothic polychrome altarpiece was created between 1477 and 1489. Paul Almasy/Corbis After Sluter's death in 1406, his influence spread from Burgundy to the south of France, to Spain, and later to Germany. By 1500, however, with Michel Colombe and the Mannerists of the school of Troyes in France and with Tilman Riemenschneider, Veit Stoss, and Adam Kraft in Germany, the era of Gothic sculpture drew to its close. C Architecture In France, late Gothic architecture is known as flamboyant, from the flamelike forms of its intricate curvilinear tracery. The ebullient ornamentation of the flamboyant style was largely reserved for the exteriors of the churches. The interiors underwent a drastic simplification by eliminating the capitals of all the piers and reducing them to plain masonry supports. All architectural ornamentation was concentrated in the vaults, the ribs of which formed an intricate network of even more complicated patterns. C1 Flamboyant Style Hôtel de Ville, Leuven, Belgium The ornately decorated Hôtel de Ville (town hall) in Leuven, Belgium, dates from the 15th century. It is widely regarded as one of the finest examples of flamboyant Gothic architecture in Europe. Leuven is situated in the Flemish province of Brabant. Robert Harding Picture Library Flamboyant architecture originated in the 1380s with French court architect Guy de Dammartin. The great surge in building activity, however, came only with the conclusion of the Hundred Years' War in 1453, when throughout France churches were being rebuilt in the new style. The last flowering of flamboyant architecture occurred between the end of the 15th century and the 1530s in the work of Martin Chambiges and his son Pierre, who were responsible for a series of grand cathedral facades, including the west front of Troyes Cathedral and the transept facades of Senlis and Beauvais cathedrals. Disseminated over much of the Continent, flamboyant architecture produced its most extravagant intricacies in Spain. In Portugal, during the reign of King Manuel I, from 1495 to 1521, it developed into a national idiom known as the Manueline style, marked by a profusion of exotic motifs. C2 Perpendicular Style Interior of King's College Chapel The chapel at King's College, Cambridge, England, is an example of the Perpendicular architectural style. The building of the chapel was proposed in 1441, but the Wars of the Roses (1455-1485) caused a delay. Construction of the chapel began again in 1508 and was completed in 1515. The fan vaulting in the ceiling, seen here, is one of the highlights of the chapel. The organ screen was added in the 1530s. John Bethell/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Spurning the flamboyant style altogether, the English builders devised their own late Gothic architecture, the Perpendicular style. The use of a standard module consisting of an upright traceried rectangle, which could be used for wall paneling and window tracery alike, resulted in an extraordinary unity of design in church interiors. The masterpiece of the style, the chapel of King's College (begun 1443), Cambridge, achieves a majestic homogeneity through the use of the new fan vaulting, the fan-shaped spreading panels of which are in complete accord with the rectangular panels of the walls and windows. C3 Secular Buildings The list of important secular monuments in the late Gothic period is long. In Belgium the series of grand civic halls, some with tall belfried towers, begins very early with the great Cloth Hall (completed 1380, destroyed 1915) of Ieper and continues with such later town halls as those of Leuven (1448-1463) and Oudenaarde (1526-1530). In England and France the austere castles of the 12th and 13th centuries had been little affected by the ecclesiastical architecture. In the last quarter of the 14th century, however, the grim fortresses were gradually replaced by graceful châteaux and impressive palaces that sometimes were the source of important architectural innovations. The earliest monument in the flamboyant style, the large screen (1388) with traceried gables that surmounts the triple fireplace in the ancient Palais des Comtes at Poitiers, foreshadowed the pieced decorative gables on the exteriors of the flamboyant-style churches. In about 1390 the largest of all medieval halls, that of London's Westminster Palace, was provided with a magnificent oaken hammer beam roof that furnished the prototype for numerous similar roofs in the parish churches of English towns. In France from the late 15th century to the 1520s, new châteaux in the flamboyant style were being built extensively, from Amboise (1483-1501) and Blois (14981515) on the Loire, to Josselin (early 16th century) in Brittany. The crowning features of their exteriors are those magnified versions of dormer windows, the lucarnes. Sometimes, as on the facade added in 1508 to the Palais de Justice at Rouen, the ornate lucarnes are each flanked by their own diminutive flying buttresses. Other regional styles of secular architecture also flourished, from the Venetian Gothic of the Doges' Palace (begun 1345?) and the Ca d'Oro (1430?) to the Tudor Gothic of Hampton Court (1515-1536) on the Thames and the Collegiate Gothic, which at Oxford lingered into the early 17th century. By this time on the Continent, however, the luxuriant growth of late Gothic forms had long since been replaced by the more intellectual and calculated architectural principles of the Renaissance. See also Architecture; Romanesque Art and Architecture; Sculpture; Renaissance Art and Architecture. Contributed By: William M. Hinkle Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.