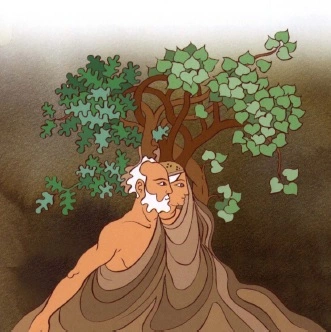

From Bulfinch's Mythology: Baucis and Philemon - anthology. This Roman fable celebrates the life-long love of a kind and modest couple. Baucis and her husband, Philemon, provide hospitality to the gods Jupiter and Mercury, who appear disguised as travelers, when no one else would be bothered with them. The gods offer to reward them for their kindness, and they reply that since they have lived together they would like to die together. After they lived out their lives, Baucis and Philemon were transformed into two trees with intertwining limbs. Thomas Bulfinch, a 19th-century American writer who chronicled Greek and Roman mythology, retells the story here. From Bulfinch's Mythology: Baucis and Philemon By Thomas Bulfinch On a certain hill in Phrygia stands a linden tree and an oak, enclosed by a low wall. Not far from the spot is a marsh, formerly good habitable land, but now indented with pools, the resort of fen-birds and cormorants. Once on a time Jupiter, in human shape, visited this country, and with him his son Mercury (he of the caduceus), without his wings. They presented themselves, as weary travellers, at many a door, seeking rest and shelter, but found all closed, for it was late, and the inhospitable inhabitants would not rouse themselves to open for their reception. At last a humble mansion received them, a small thatched cottage, where Baucis, a pious old dame, and her husband Philemon, united when young, had grown old together. Not ashamed of their poverty, they made it endurable by moderate desires and kind dispositions. One need not look there for master or for servant; they two were the whole household, master and servant alike. When the two heavenly guests crossed the humble threshold, and bowed their heads to pass under the low door, the old man placed a seat, on which Baucis, bustling and attentive, spread a cloth, and begged them to sit down. Then she raked out the coals from the ashes, and kindled up a fire, fed it with leaves and dry bark, and with her scanty breath blew it into a flame. She brought out of a corner split sticks and dry branches, broke them up, and placed them under the small kettle. Her husband collected some pot-herbs in the garden, and she shred them from the stalks, and prepared them for the pot. He reached down with a forked stick a flitch of bacon hanging in the chimney, cut a small piece, and put it in the pot to boil with the herbs, setting away the rest for another time. A beechen bowl was filled with warm water, that their guests might wash. While all was doing, they beguiled the time with conversation. On the bench designed for the guests was laid a cushion stuffed with sea-weed; and a cloth, only produced on great occasions, but ancient and coarse enough, was spread over that. The old lady, with her apron on, with trembling hand set the table. One leg was shorter than the rest, but a piece of slate put under restored the level. When fixed, she rubbed the table down with some sweet-smelling herbs. Upon it she set some of chaste Minerva's olives, some cornel berries preserved in vinegar, and added radishes and cheese, with eggs lightly cooked in the ashes. All were served in earthen dishes, and an earthenware pitcher, with wooden cups, stood beside them. When all was ready, the stew, smoking hot, was set on the table. Some wine, not of the oldest, was added; and for dessert, apples and wild honey; and over and above all, friendly faces, and simple but hearty welcome. Now while the repast proceeded, the old folks were astonished to see that the wine, as fast as it was poured out, renewed itself in the pitcher, of its own accord. Struck with terror, Baucis and Philemon recognized their heavenly guests, fell on their knees, and with clasped hands implored forgiveness for their poor entertainment. There was an old goose, which they kept as the guardian of their humble cottage; and they bethought them to make this a sacrifice in honour of their guests. But the goose, too nimble, with the aid of feet and wings, for the old folks, eluded their pursuit, and at last took shelter between the gods themselves. They forbade it to be slain; and spoke in these words: 'We are gods. This inhospitable village shall pay the penalty of its impiety; you alone shall go free from the chastisement. Quit your house, and come with us to the top of yonder hill.' They hastened to obey, and, staff in hand, laboured up the steep ascent. They had reached to within an arrow's flight of the top, when, turning their eyes below, they beheld all the country sunk in a lake, only their own house left standing. While they gazed with wonder at the sight, and lamented the fate of their neighbours, that old house of theirs was changed into a temple. Columns took the place of the corner posts, the thatch grew yellow and appeared a gilded roof, the floors became marble, the doors were enriched with carving and ornaments of gold. Then spoke Jupiter in benignant accents: 'Excellent old man, and woman worthy of such a husband, speak, tell us your wishes; what favour have you to ask of us?' Philemon took counsel with Baucis a few moments; then declared to the gods their united wish. 'We ask to be priests and guardians of this your temple; and since here we have passed our lives in love and concord, we wish that one and the same hour may take us both from life, that I may not live to see her grave, nor be laid in my own by her.' Their prayer was granted. They were the keepers of the temple as long as they lived. When grown very old, as they stood one day before the steps of the sacred edifice, and were telling the story of the place, Baucis saw Philemon begin to put forth leaves, and old Philemon saw Baucis changing in like manner. And now a leafy crown had grown over their heads, while exchanging parting words, as long as they could speak. 'Farewell, dear spouse,' they said, together, and at the same moment the bark closed over their mouths. The Tyanean shepherd still shows the two trees, standing side by side, made out of the two good old people. The story of Baucis and Philemon has been imitated by Swift [18th-century satirist Jonathan Swift], in a burlesque style, the actors in the change being two wandering saints, and the house being changed into a church, of which Philemon is made the parson. The following may serve as a specimen: 'They scarce had spoke, when, fair and soft, The roof began to mount aloft; Aloft rose every beam and rafter; The heavy wall climbed slowly after. The chimney widened and grew higher, Became a steeple with a spire. The kettle to the top was hoist, And there stood fastened to a joist, But with the upside down, to show Its inclination for below; In vain, for a superior force, Applied at bottom, stops its course; Doomed ever in suspense to dwell, 'Tis now no kettle, but a bell. A wooden jack, which had almost Lost by disuse the art to roast, A sudden alteration feels. Increased by new intestine wheels; And, what exalts the wonder more, The number made the motion slower; The flier, though 't had leaden feet, Turned round so quick you scarce could see 't; But slackened by some secret power, Now hardly moves an inch an hour. The jack and chimney, near allied, Had never left each other's side: The chimney to a steeple grown, The jack would not be left alone; But up against the steeple reared, Became a clock, and still adhered; And still its love to household cares By a shrill voice at noon declares, Warning the cook-maid not to burn That roast meat which it cannot turn. The groaning chair began to crawl, Like a huge snail, along the wall; There stuck aloft in public view, And with small change, a pulpit grew. A bedstead of the antique mode, Compact of timber many a load, Such as our ancestors did use, Was metamorphosed into pews, Which still their ancient nature keep By lodging folks disposed to sleep.' Source: Bulfinch, Thomas. Bulfinch's Mythology: The Age of Fable, The Age of Chivalry, Legends of Charlemagne. New York: Random House, 1934.