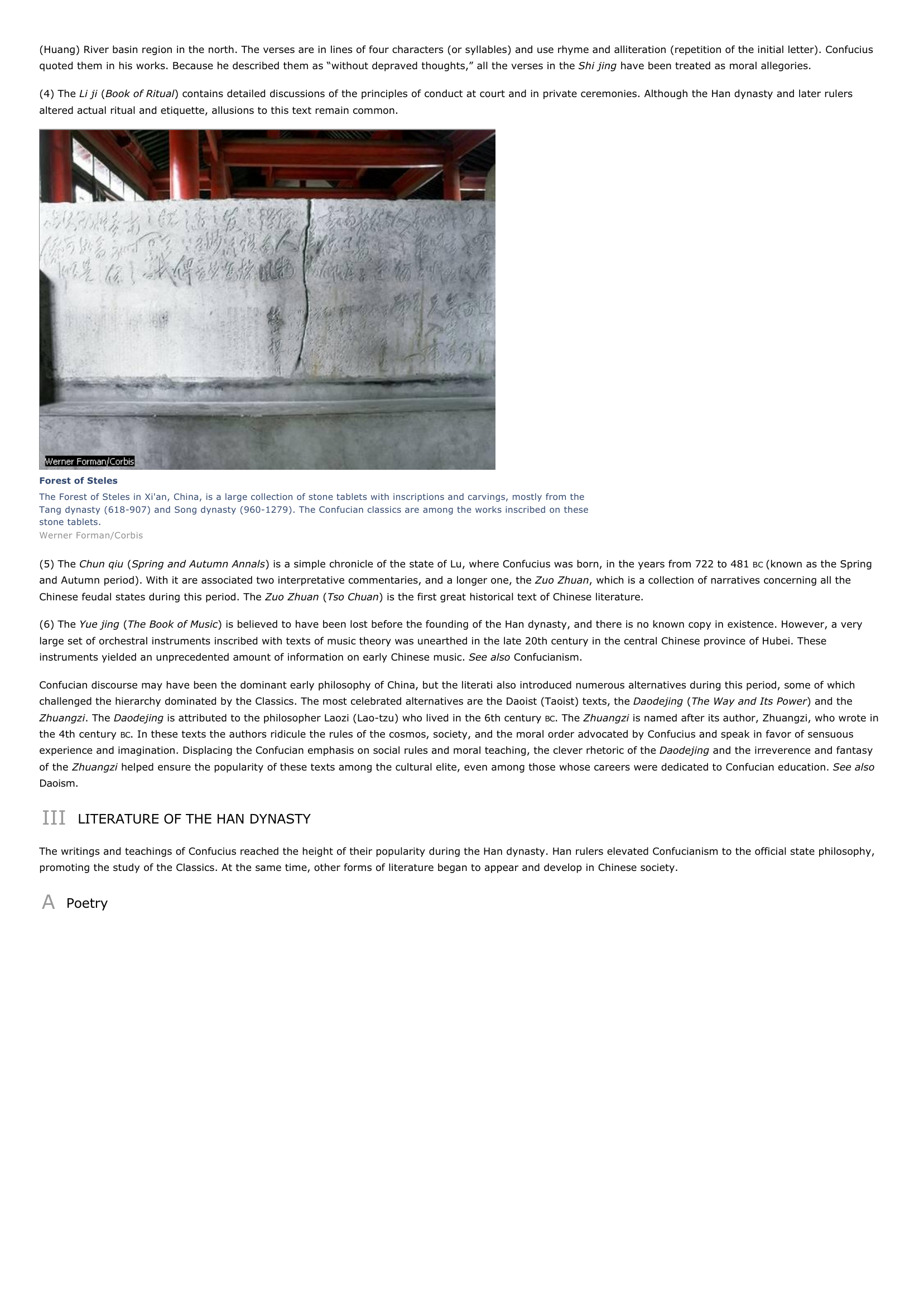

Chinese Literature I INTRODUCTION Chinese Literature, writings of the Chinese people, with a continuous history of more than 3,000 years. It is the literature of a large multicultural area that became an empire in the 3rd century BC. This empire lasted until 1911, when the Republic of China was formed. Most of the literature prior to the 20th century was written or collected by officials who were part of the imperial system or by men educated as a part of this system. Chinese literature therefore has many connections with the history of China and with the major philosophical and religious beliefs of the society. Poetry and essays were the major forms of Chinese literature prior to the 20th century. Yet over the centuries the Chinese also developed traditions of fiction and drama. While Chinese literature has adopted many literary forms from its wide contact with other cultures, all forms of Chinese literature, in turn, have had a major influence on the writings of Korea, Japan, and neighboring countries of Central and Southeast Asia. II THE CLASSICS Confucius During the age of Chinese feudalism, when intrigue and vice were rampant, Confucius taught principles that embraced high ethical and moral standards. He urged the feudal leaders to live by those standards and serve as examples to their subjects. An aristocrat of the 6th century bc, Confucius was China's first great philosopher. His teachings about ethics and the role of individuals in society form the 12-volume Lunyu (The Analects). Respect for tradition and for elders underlies much of Confucius's instruction. His work helped define Chinese culture for more than 2,000 years. Hulton Deutsch Most of the writing attributed to the first 1,000 years of Chinese literature is contained in a set of texts endorsed in the 6th century record of his conversations entitled Lunyu (The Analects). From the founding of the Han dynasty at the end of the 3rd century BC BC by the philosopher Confucius in a until the 20th century, these texts formed the pinnacle of a literary hierarchy that was maintained by an officially sponsored educational system. This system served as an important avenue to government position and membership in the cultural elite, who were known as the wenren (literati or educated class). Confucius was one of a diverse group of philosophers who offered their services as advisers on good government to the rulers of several feudal states within the ruling house of Zhou, a dynasty that held power from about 1045 to 256 BC. Dismayed by the immorality of his times, Confucius called for governments to uphold the official rituals and etiquette of earlier generations of the Zhou dynasty. The ancient texts, he claimed, recorded the success of the early Zhou dynasty in regulating behavior, and their success underscored the importance of proper ritual and etiquette, which demonstrated respect for the order of the heavenly realm and the earthly realm. Music and verse, Confucius said, were important elements inspiring rulers and subjects to proper feelings and conduct. The texts promoted by Confucius became known in later centuries as Jing (Classics), taking their final form after the Han empire adopted them as a state orthodoxy in the last two centuries BC. Brief descriptions of the six Confucian Classics follow. (1) The I Ching (Yi jing, or Book of Changes) presents the universe and human society as constantly changing but having a definable order. This order can be described through 64 six-line diagrams known as hexagrams, which were originally used for fortune-telling. Later scholars enlarged upon the hidden meanings of the diagrams and interpreted the I Ching as a philosophical text that comments on moral truths. The text remains popular today. Teachings of Confucius Nearly 2500 years ago when intrigue and vice were rampant in feudal China, the philosopher Confucius taught principles of proper conduct and social relationships that embraced high ethical and moral standards. Confucius's teachings and wisdom were standard scholarly education for the bureaucrats who administered the country. The Confucian tradition, which encompasses education, wisdom, and ethics, persists in China. National Palace Museum, Taiwan/Robert Harding Picture Library (2) The Shu jing (Book of History) purports to be a collection of speeches, discussions, and other matter from the 3rd millennium BC to the 6th century BC, but much of BC, presumably near the Yellow it is clearly more recent. The Shu jing concerns itself primarily with the practices of good government. (3) The Shi jing (Book of Songs) is a collection of folk songs, love poems, and ceremonial odes composed between 1200 and 600 (Huang) River basin region in the north. The verses are in lines of four characters (or syllables) and use rhyme and alliteration (repetition of the initial letter). Confucius quoted them in his works. Because he described them as "without depraved thoughts," all the verses in the Shi jing have been treated as moral allegories. (4) The Li ji (Book of Ritual) contains detailed discussions of the principles of conduct at court and in private ceremonies. Although the Han dynasty and later rulers altered actual ritual and etiquette, allusions to this text remain common. Forest of Steles The Forest of Steles in Xi'an, China, is a large collection of stone tablets with inscriptions and carvings, mostly from the Tang dynasty (618-907) and Song dynasty (960-1279). The Confucian classics are among the works inscribed on these stone tablets. Werner Forman/Corbis (5) The Chun qiu (Spring and Autumn Annals) is a simple chronicle of the state of Lu, where Confucius was born, in the years from 722 to 481 BC (known as the Spring and Autumn period). With it are associated two interpretative commentaries, and a longer one, the Zuo Zhuan, which is a collection of narratives concerning all the Chinese feudal states during this period. The Zuo Zhuan (Tso Chuan) is the first great historical text of Chinese literature. (6) The Yue jing (The Book of Music) is believed to have been lost before the founding of the Han dynasty, and there is no known copy in existence. However, a very large set of orchestral instruments inscribed with texts of music theory was unearthed in the late 20th century in the central Chinese province of Hubei. These instruments yielded an unprecedented amount of information on early Chinese music. See also Confucianism. Confucian discourse may have been the dominant early philosophy of China, but the literati also introduced numerous alternatives during this period, some of which challenged the hierarchy dominated by the Classics. The most celebrated alternatives are the Daoist (Taoist) texts, the Daodejing (The Way and Its Power) and the Zhuangzi. The Daodejing is attributed to the philosopher Laozi (Lao-tzu) who lived in the 6th century the 4th century BC. BC. The Zhuangzi is named after its author, Zhuangzi, who wrote in In these texts the authors ridicule the rules of the cosmos, society, and the moral order advocated by Confucius and speak in favor of sensuous experience and imagination. Displacing the Confucian emphasis on social rules and moral teaching, the clever rhetoric of the Daodejing and the irreverence and fantasy of the Zhuangzi helped ensure the popularity of these texts among the cultural elite, even among those whose careers were dedicated to Confucian education. See also Daoism. III LITERATURE OF THE HAN DYNASTY The writings and teachings of Confucius reached the height of their popularity during the Han dynasty. Han rulers elevated Confucianism to the official state philosophy, promoting the study of the Classics. At the same time, other forms of literature began to appear and develop in Chinese society. A Poetry Qu Yuan Qu Yuan, a government official in the state of Ch'u in the 4th century bc, wrote one of the most famous texts in early Chinese literature, "Li Sao" ("Encountering Sorrow"). The poem, about a man with an unfaithful lover, is an allegory about losing one's place in society and being forced into exile. National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China Poetry during the Han empire encompassed not only the verse forms inherited from the Book of Songs, but also verses inspired by shamanistic spiritual practices--practices that involved communication with the spirit world--along the semitropical Yangtze River basin. These verses were collected as the Chu ci (Songs of the South). The most famous poem of this collection, the "Li Sao" ("Encountering Sorrow"), is attributed to Qu Yuan, an adviser to the state of Chu in the 4th century BC. This long verse presents the adviser's loss of favor with the king of Chu and subsequent exile as an allegory of a man whose loved one is unfaithful, prompting him to set out on an imaginary journey through the world and beyond. Chu ci inspired and influenced a form of prose-poetry known as fu, which was developed by poets in the Han court. Fu rose to prominence as court literature that featured elaborate descriptions in praise of the greatness of Han capitals and palaces, the magnificence of their parks, the beauty of the imperial flora and fauna, and the pleasures of court entertainments. The early genius of fu verse was poet Sima Xiangru, who wrote in the 2nd century BC. He is most remembered for employing his talent with verse and lute to entice the daughter of a Sichuan iron-master to elope with him. B Prose Sima Qian One of the most significant works of early Chinese prose is historian Sima Qian's Shi ji (Records of the Historian), written around the 2nd century bc. It is an exhaustive history of China that includes official state papers, traditional narratives, monographs on important topics, and biographies of many of the famous figures in the country's history. National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China The major work of prose surviving from the Han dynasty is a general history, the Shi ji (Records of the Historian). This text was completed by historian Sima Qian and covers China's history from legendary times to his own age, the 2nd century BC, in 130 chapters. The Shi ji established the general form used by all 24 official histories of the dynasties. It is largely a compilation of original source material, state papers, traditional narratives, and poems and prose compositions, and is organized in five parts: (1) annals of the emperors (12 chapters); (2) chronological tables (10 chapters); (3) monographs on such topics as the calendar, rivers and canals, and state sacrifices (8 chapters); (4) annals of the princely houses (30 chapters); and (5) narratives, mainly biographies of important men (70 chapters). Other surviving prose from the Han empire consists of memorials and edicts, official and private letters, prefaces, narratives, descriptions, essays, epitaphs, addresses to the dead, and other short pieces. The heritage of Confucian moral teaching is exemplified in the essay "Guo Qin Lun" ("The Faults of Qin"). In this essay the 2ndcentury-BC imperial tutor Jia Yi describes the sudden fall of China's first true empire--the Qin dynasty, which preceded the Han--as a warning to his own ruler. However, even a court figure such as Jia Yi was drawn to ideas outside Confucianism; his contemplation of death, "Fu niao fu" ("The Owl"), incorporates Daoist ideas and takes the form of a fashionable fu prose-poem. IV POST-CONFUCIAN LITERATURE At the beginning of the 3rd century AD China's Han dynasty collapsed into political disunity and civil war. This disintegration shook the status of Confucianism and its literary hierarchy. During the Han dynasty this hierarchy had expanded to incorporate new forms, including those cited above and several others. For example, early in the Han period an imperial music bureau (Yue Fu) was established to collect folk songs, in the tradition of the Book of Songs. These folk songs included verse with lines of five characters known as shi and later as gushi (ancient style shi). Despite its folk origin, the style was gradually adopted by the cultural elite. The status of this form was consolidated in the 3rd century AD by the gifted poet Cao Zhi, son of Cao Cao who was a dominant warlord in the devastating civil wars that followed the fall of the Han. Cao Zhi skillfully constructed an image of himself in his poetry as a melancholy man oppressed by the violent politics of his time and forced to take refuge in hedonism and imaginative journeys. Other writers during this time of turmoil also developed the theme of withdrawal from involvement in the battles of rival kingdoms and their internal politics. Tao Qian, a 5th-century official, retired to what his verse describes as the life of a farmer in a gentle landscape, at ease with his family, friends, and wine. His verse and prose narrative, T'ao hua yuan (The Peach Blossom Spring), was a popular depiction of a hidden utopia peopled by refugees who did not even know of the Han dynasty's existence. Tao Qian's writing creates a Daoist ideal of community that counters the intellectual trend of the times. Prose narratives of the time also show a fascination with Daoist-inspired values, such as simplicity and spontaneity, and with events not yet incorporated into official histories or explained by official doctrines. One of these narratives, Shi shuo xin yu (A New Account of Tales of the World) by Liu Yiqing, is a 5th-century work that contains anecdotes about historical figures of the era. Another popular type of prose was zhi guai, or tales of the supernatural. Court writing gradually began to exhibit a complex style requiring paired phrases of four or six characters, a form known as pian wen (parallel prose). This style was heavily laced with allusions to the Confucian Classics. A Major Innovations The new forms of literature, no longer shaped by the Confucian canon, prompted important critical reactions. One response was the first established text of Chinese literary criticism, the Wen xin diao long (The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons) by 6th-century writer Liu Xie. It upheld the value of literature according to its fidelity to Confucian precepts. Liu Xie nevertheless established the critique of literary form as a separate category of literature. By 531 scholar Xiao Tong had compiled the first major anthology of Chinese literature, the Wen xuan (Selections of Refined Literature), consisting of nearly 800 works organized into 37 literary categories. Despite their conservative emphasis on Confucianism, these anthologies and works of criticism sought to incorporate shifting cultural practices into an overarching tradition. The new literary trends were little altered by such critical responses, however. China in the post-Han era also absorbed inspiration from Buddhism and writings from India that were translated from Sanskrit into Chinese. Buddhism gained strength in China as disorder increased and the domination of Confucian thought diminished. The first major sign of this influence on literature was the adoption of elements of Sanskrit poetic structure, which resulted in two new Chinese verse forms: jue ju (curtailed verse) and lü shi (regulated verse). Both of the verse forms have lines of five or seven characters, or syllables, and each line has a prescribed tonal pattern and alternating rhyme. Curtailed verse is organized in four lines, and regulated verse in eight lines. Too short to tell a story, curtailed verse seeks instead to create a mood in an economical manner. The longer regulated verse is based on coupled lines that are parallel in sound, thought, and tone. The next great Chinese empire, the Tang dynasty (618-907), produced the most famous poets to write in the new verse forms. Among them is the writer many critics consider China's greatest poet, Du Fu, who created in his poetry an image of himself as the sober statesman. After a rebellion in the Tang capital, Du Fu became a refugee and his poetry turned melancholy, as in these lines from "Spring Prospect": The capital is taken. The hills and streams are left, And with spring in the city the grass and trees grow dense. Mourning the times, the flowers trickle their tears; Saddened with parting, the birds make my heart flutter. Others who helped perfect the new verse forms during the Tang dynasty include Li Bo, who wrote in the guise of the wine-inspired genius; the humorous and sentimental Bo Juyi, and the enigmatic Li Shangyin. Among the cultural elite, Buddhist ideas themselves found expression in the landscape painter and poet Wang Wei and the Zen poet Han Shan. Modern discoveries of 10th-century manuscripts in the northwestern city of Dunhuang show that Buddhists promoted their beliefs and gained converts through marketplace storytellers. The most representative example of these stories, which are called bianwen, is about a young man who demonstrates such filial piety that the Buddha is moved to save his mother from punishment in hell and reincarnation as a dog. Dunhuang became a center for the translation and copying of Buddhist texts from India and Central Asia. Popular music along the Central Asian borders of the empire also increasingly found its way into the high culture of China. This music provided a new form of lyric, the ci, in which lines of uneven lengths are set in a prescribed pattern and matched to tunes. This music was lost several centuries ago, although the form was practiced well into the 20th century. B Conservative Reactions Following a political crisis in the Tang empire, literati officials loyal to the central government began an attack on Buddhism, parallel prose, and other aspects of culture that they felt violated Confucian beliefs. Their most articulate spokesperson was the 9th-century poet and essayist Han Yu, who sought to reunify and consolidate the culturally and politically fragmenting empire under central authority. Han reasserted the value of writing styles found in the Classics and the histories prior to the advent of parallel prose and Buddhist texts, forcing students to study the ancient texts instead. The conservative reaction did not preserve the Tang dynasty for long, but it did establish a direction for high culture that dominated the next great dynasty, the Song (960-1279). The most widely read and oft-cited of the poets and essayists of the Song dynasty were Ouyang Xiu and Su Dongpo (also known as Su Shi). As much as they championed Han Yu's promotion of ancient-style prose (gu wen), both Ouyang and Su became better known for their devotion to the newer ci lyric form and their expansion of its content to include reflections on historical and philosophical issues. Su freed the ci from its rigid meter. This excerpt from Su's poem "Written on a Painting Entitled 'Misty Yangtze and Folded Hills' in the Collection of Wang Dingguo" illustrates his powers of observation and description: Above the river, heavy on the heart, thousandfold hills: layers of green floating in the sky like mist. Mountains? clouds? too far away to tell till clouds part, mist scatters, on mountains that remain. Then I see, in gorge cliffs, black-green clefts where a hundred waterfalls leap from the sky, threading woods, tangling rocks, lost and seen again, falling to valley mouths to feed swift streams. Confucianism itself was changing during the Song dynasty. The chief architect of what became known as Neo-Confucianism was 12th-century philosopher Zhu Xi, who incorporated aspects of Daoist and Buddhist thought into his commentaries on the Confucian Classics. He further abstracted passages from the Book of Ritual and combined these with Confucius's Analects and the Book of Mencius to create a core curriculum for students entering civil service education. This collection was known as the Sishu (The Four Books), and these works are sometimes counted among the Confucian Classics. V LITERATURE OF THE LATE IMPERIAL PERIOD The hold that government officials and the educational elite had over literature began to weaken as larger cultural shifts took place within Song society, although Confucianism in some form kept its position in the educational curriculum and as official belief. First, Song rulers carried through reforms to make education far more available to commoners, fostering more readers and writers. Second, printing developed as a commercial enterprise and made the written word much more widely available. Third, in the increasingly commercial economy during and after the Song, merchants and landowners outside the nobility gained power and supported new forms of entertainment. Fourth, the Mongols conquered China and replaced the Song with the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), alienating a group of scholars who refused to participate in the new regime. This refusal established the literati as something other than government officials, and their other interests--including literature--became an important means to express their identity as a semi-autonomous social group. With that new identity went expressions of independence from conventional, statesupported interpretations of Confucianism--if not from Confucianism itself--as well as from state-sponsored literary values. A Music Theater The earliest demonstrations of this gradual cultural shift may have appeared in music theater. This form of entertainment evolved during the empires of the Southern Song (1127-1279), the Jin (1115-1234), and the Yuan. Music theater employed the latest musical tunes from Central Asia, called qu, and developed into light opera, which was performed in various sites--from the marketplace to the teahouse, the homes of wealthy patrons, and the imperial court. Qu were similar in form to the earlier ci tunes of the Tang and Song, and the stories ranged from domestic drama to crime cases and to famous romantic or martial episodes from legend and history. These increasingly elaborate conceptions eventually became masterpieces of literary creation that dealt with subtle and profound questions about the cultural order of the empire. By the time of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) and the early Qing dynasty (1644-1911), music theater featured famous writers whose scripts were published in expensive editions. Emperors passed judgment on the most celebrated piece of the moment. The operas with the most enduring reputations include the comic Xi xiang ji (The Story of the Western Wing) by Wang Shifu, from the Yuan dynasty; the romantic Mu Danting (The Peony Pavilion) by Tang Xianzu, from the Ming dynasty; and Tao hua shan (The Peach-Blossom Fan) by Kong Shangren, from the early Qing dynasty. All of these operas concern the fate of love relationships at odds with social convention and political power. See also Asian Theater. B Fiction Journey to the West Journey to the West is a 16th-century Chinese novel, full of comic adventures, about the travels of a Buddhist monk and his animal disciples to India in search of Buddhist scriptures. This classic work of Chinese literature is attributed to Wu Cheng'en. (C)Yasuo Segawa Along with musical theater, fiction written in the vernacular (spoken language) is the other great innovative achievement of late imperial Chinese literature. It is also the achievement that made Chinese literature most accessible to modern readers. The move from literary language to the vernacular was a giant step. Although Chinese music theater contained much dialogue in the spoken language, song lyrics still provided a showcase for verse writing. Fiction written in the vernacular completed the transition. See also Chinese Language. Prior to the Tang dynasty (618-907), fiction describing supernatural events was written in literary language, and the engaging short fiction of the Tang dynasty was also written in an educated, literary style. This form of fiction, the chuanqi, focused on love, adventure, and the supernatural and continued as a tradition of its own through the 18th century. The best-known collection of chuanqi is Liao zhai zhi yi (Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio) by Pu Songling, who lived in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. By the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), however, commercial printers were publishing collections of stories and full-length novels largely written in the spoken language of the time. Novels of the 14th and 15th centuries were mainly tales of adventure and conquest taken from historical records and reworked using unofficial legends and popular religion. The most celebrated novel of this genre is San guo yanyi (Romance of the Three Kingdoms), attributed to Luo Guanzhong. It tells of the great civil war that followed the collapse of the Han dynasty. Whereas official histories had favorably recorded the achievements of the most successful warlord of this period, Cao Cao, he was preserved in unofficial anecdotes and legends as a major villain. The novel offers a complex portrait of him as a villain, alongside more admiring portraits of his chief adversaries, Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei, together with an adviser in popular Daoist magic, Zhuge Liang. Although many Chinese novels of this era are simply exciting stories that reflect popular tastes in heroes and religious beliefs, a number of novels made more complex use of these elements. Shui hu zhuan (All Men Are Brothers, also known as Outlaws of the Marsh or Water Margin) is the history and legend of a bandit army in revolt against a corrupt regime during the Song dynasty. The story itself has ancient origins, but the earliest complete versions known were published in the 1500s. The novel is a masterpiece of vivid description that leaves unresolved whether the bandits are popular heroes, ruthless killers, or agents of a vengeful heaven. Another novel, Xi you ji (1592; Monkey, or Journey to the West, 1943), based on accounts of a Buddhist pilgrim's travels to India, has all the comic adventure and fantastic qualities of a lively children's story, complete with a magical monkey. The work, attributed to 16th-century writer Wu Cheng'en, also contains reflections on myth and a complex religious allegory that make it an intellectual challenge for readers. By the late 16th century the novel had moved from history and legend to include accounts of social manners and domestic life. This change also ushered in a wave of graphically detailed erotic fiction. The acknowledged landmark representing both literary trends is Jin ping mei (Golden Lotus, or The Plum in the Golden Vase), about three of the six wives of a drug merchant and pawnbroker, whose ambition to achieve wealth and social status is exceeded only by his sexual desire. During the 18th century this controversial novel helped inspire Cao Xueqin (Cao Zhan), the author of the single greatest masterpiece of Chinese fiction, Hong lou meng (1792; variously translated as Dream of the Red Chamber, 1929; Story of the Stone, 1973; and A Dream of Red Mansions, 1978). Almost certainly based on the childhood experiences of the author, the book is about a young boy in an aristocratic household who detests his destined career and stubbornly pursues his sentimental devotion to the girls in his household, especially his frail and temperamental cousin. The book also has a large section that was added on by another writer, Gao E. Hong lou meng was the fulfillment of a goal for Chinese literati who sought a literature that could rival the ancient texts they were taught to study. Interweaving a large cast of characters and their conflicts with unprecedented originality and inventiveness, the book is full of allegories relating to the intellectual issues of the time. It is also full of realistic detail that makes it an important document of 18th-century life. Cao Xueqin lived and worked in obscurity, however, and the novel was not published until almost 30 years after his death. VI THE COLLAPSE OF TRADITIONS Until 1911 and the end of the Qing empire--the last imperial dynasty in Chinese history--the Confucian Classics and the poetry and essays of official scholars remained at the pinnacle of the literary and educational hierarchy. But as the Chinese imperial system unraveled and the country confronted modernity as introduced by powerful Western nations, the old literary order was replaced as well. A Transformation of the Novel This transformation was reflected in the novel, the literary form most sensitive to the fundamental changes sweeping the country. Novels criticizing the leadership of the cultural and political elite grew in number during the Qing, from Wu Jingzi's Ru lin wai shi (1768; The Scholars, 1957) to Lao Can you ji (1903-07; The Travels of Lao Can, 1952) by Liu E. The Travels of Lao Can poignantly illustrates the changes occurring in China during this period. Its hero, an itinerant scholar practicing Chinese medicine, searches out evidence of the great Chinese tradition of knowledge that has been lost by the cultural and political elite of his day. The novel shows that with proper understanding or knowledge reform can occur. This work, first published in the new Chinese newspapers and magazines appearing in the cities built and controlled by Western colonial powers, shows an acceptance of Western innovations set inside the form of the Chinese novel. The changing values of society and the resistance to change by the traditionally educated literati resulted in the publication of two very different types of novels. One type was set in the brothels of the modernizing port city of Shanghai, where prostitutes are presented as understanding the city better than their customers. Another type presented young heroes or heroines who rejected all romantic passion for the traditional ideals of chastity and devotion to religious or political beliefs, with characters speaking in largely ancient-style language. The erosion of the traditional literary hierarchy began in 1905 when the Qing government abolished the official civil service examination and thereby severed the link between literary education and positions of political authority. At the same time, large numbers of students were sent to Japan and Western countries for study. Those who wanted to be modern-style writers had no interest in existing Chinese newspapers and magazines, whose editors had been trained in the traditional civil service education system. Therefore, foreign-educated Chinese writers associated themselves with the new Chinese universities then being established and started magazines and journals of their own, dedicated to their radical beliefs. Following the Republican Revolution of 1911 and 1912, the new literary intellectuals launched a movement to end the use of ancient classical language and the study of ancient texts. They supported instead using the spoken language for all writing and the creation of a new Chinese literature on the model of modern European literatures. The chief spokespersons for this "literary revolution" were Hu Shi, who studied in the United States and later served as an ambassador to that country, and Chen Duxiu, who studied in Japan and was a founder of the Communist Party of China in 1921. B Realism and Revolution Lu Xun Lu Xun is one of the most important figures in 20th-century Chinese literature. An acclaimed writer of fiction, essays, and literary theory, Lu Xun was also a social critic and activist who helped spark protests against the Chinese government during the early decades of the century. Corbis The period from 1917 to 1927 was one of cultural ferment in China. A wave of Chinese translations of Western authors appeared, and Chinese writers made numerous attempts at writing poems, essays, short stories, and one-act plays in the Western manner. Their common theme was emancipation--from classical restraint, from the Confucian family system, and from imperialism. While a romantic emotionalism dominated much of the new literature, the chief writer to emerge from this period was the pessimistic Lu Xun. His "Kuangren Riji" ("Diary of a Madman," 1918) is sometimes called China's first modern story. Lu Xun shared the period's passion for social justice and change, but he had grim doubts that society would respond. The decades leading up to the Communist Revolution in 1949 were marked by protest against social inequality. The politics of many writers took a leftward turn, summed up in the slogan "From Literary Revolution to Revolutionary Literature." Yet the key works inspired by Marxism during this period, such as the fiction of Mao Dun and the polemical essays of Lu Xun, were independent of--and even clashed with--Communist Party prescriptions. Moreover, authors who did not embrace Marxism wrote most of the period's major works. These writers included Shu Qingchun (Lao She), author of Luotuo xiangzi (1936-1937; Rickshaw or Rickshaw Boy, 1979); Ba Jin, author of Jia (1931-1932; Family, 1972); and Shen Congwen, who was known for the compilation The Selected Works of Shen Congwen (1936). The most accomplished writer of the time, Qian Zhongshu, enjoyed satirizing the cultural elite of his era. At the same time he embedded his characters in a world without order or reassuring purpose, as in the novel Wei ch'eng (1946; Fortress Besieged, 1979). C Literature of the People's Republic Efforts to create individual literary styles dwindled with the Communists' rise to power in China during the late 1940s. Chinese Communist literary theory regarded all literature as an educational propaganda tool and insisted that literary works be written for mass consumption and conform to current political tasks as defined by the Party and the government. The major Chinese works of fiction from the late 1940s through the 1970s dealt with successive movements to achieve agricultural reforms. This trend began with the novel Tai yang zhao zai Sanggan he shang (1948; The Sun Shines Over the Sanggan River, 1955) by Ding Ling. The continued dissent of writers from official policy provoked government purges, most notably during the Hundred Flowers Period of 1956 and 1957, when Chinese leaders first encouraged and then cracked down on criticism of the government. Writers were thereafter directed to stress "revolutionary romanticism" by portraying idealized, utterly selfless characters dedicated to socialism. This policy was best realized in Liu Qing's novel Chuang ye shi (1960; The Builders, 1964). With the launching of the massive Cultural Revolution in 1966, virtually the entire modern literary establishment in China was silenced. In its place arose new cultural organizations whose most prominent offerings were a series of "revolutionary model" operas and ballets (geming yangbanxi), strongly supporting the political policies and goals of the regime, and works of fiction by an author of peasant origins, Hao Ran. All of these emphasized struggle between idealized heroic figures and subversives opposed to the philosophies of Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong. Following the upheavals of the Cultural Revolution, which ended with the death of Mao in 1976, there was a general restoration of many previously disgraced writers and cultural officials, together with a return to the more liberal atmosphere of the early 1960s. But it had become clear by early 1979 that party officials were not prepared to relinquish ideological and social controls on literature. D Outside Mainland China A literature of dissent authored by émigré writers began to appear outside mainland China in the 1950s. Some of this writing attracted attention in the West, notably the novel Yang ge (1954; The Rice-Sprout Song, 1955) by Eileen Chang (Zhang Ailing) and Chen Ruoxi's story collection Yin xianzhang (1976; The Execution of Mayor Yin, 1978). In Taiwan, Chinese literature entered an active period in the early 1960s with the rise of young "modernist" authors nourished on modern Western literary practice. Among these writers were Wang Wenxing, author of Jia bian (1972; Family Catastrophe, 1995), and Bai Xianyong, author of Taibei ren (1971; Wandering in the Garden, 1982). A literature of liberal social criticism also emerged in the essays of Li Ao, Yin Hai-kuang, and others heavily influenced by Western liberal thought. By the middle 1970s, however, this internationalism was under attack by a group of writers who promoted "native" or "homeland" literature, took up a number of social causes, and attacked "modernist" writers for their preoccupation with foreign literature. Writers noted for their nativist fiction--works concerned with social exploitation--included Chen Yingzhen, in stories translated under the title Exiles at Home (1986); Huang Chunming; and Wang Zhenhe, author of Meigui, meigui wo ai ni (1984; Rose, Rose, I Love You, 1998). E International Recognition Gao Xingjian Chinese dissident writer Gao Xingjian was awarded the 2000 Nobel Prize for literature. Gao, whose work is banned in China, is the first native-born Chinese writer to win the award. Among the publications cited by the Nobel Committee was Gao's novel Ling Shan (Soul Mountain, 2000). Francois Guillot/AFP In the 1980s and 1990s screenplays became the Chinese literary efforts that gained the most international recognition. Chu Tianwen and Wu Nianzhen wrote some of the best scripts, particularly Beiqing chengshi (City of Sadness, 1989). Also notable were the scripts produced by Yang Dechang (Edward Yang) and Xiao Ye for films directed by Yang, such as Kongbu fenzi (The Terrorizer, 1986), and those by the director Ang Lee (Li An) and his team, such as Xiyan (The Wedding Banquet, 1993) and Yin shi nan nü (Eat, Drink, Man, Woman, 1994). Similarly, films made for the domestic market gained widespread attention, beginning with the work of Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige. Among Zhang's landmark films was Hong gao liang (Red Sorghum, 1987), adapted from a violent novel of love and revenge by Mo Yan. Mo's book was representative of a new freedom in Chinese literature to explore history in ways not previously allowed, to revise conventional expectations of morality, and to turn writing from idealization to graphic sensuousness. Other writers would take up elements of these themes, notably Su Tong in Mi (1991; Rice, 1995) and Yu Hua in a set of novellas. Writing such as Mo's was part of a wave of cultural criticism that spread through Chinese literary and intellectual circles during the 1980s. As Maoism was discredited there was an effort to redefine Chinese history and culture, past and present, and to argue and experiment with ideas and art forms introduced from overseas. At the same time, the realms of intimate experiences and subjectivity were opened for artistic exploration. Avant-garde artists rushed to experiment. Older writers, purged by the government decades before, reassessed their experiences, as exemplified by Wang Meng's Bolshevik Salute (1990). In this novel, which resembles in its plot the author's own life, a young Communist Party activist becomes disenchanted with the Revolution and is eventually forced into manual labor in the countryside for several decades. Writers active in the Cultural Revolution as youths became modernists committed to intellectual and social freedom. The most distinguished writer of this group is the poet Bei Dao, whose works include The August Sleepwalker (1988) and Forms of Distance (1995). Others, such as Han Shaogong (Homecoming? and Other Stories, 1995), revised the modern concept of a unified nation and culture into a maze of local and regional subcultures. As the realm of intimate relationships and subjectivity returned to writing, women writers were published in large numbers for the first time in Chinese history. Notable among them were Zhang Xinxin (Chinese Lives, 1987), Can Xue (Dialogues in Paradise, 1989), and Wang Anyi (Xiaobao zhuang, 1985; Baotown, 1989). By the end of the 1980s, the atmosphere of cultural experiment combined with economic and political issues to spark massive demonstrations for reform in major Chinese cities. When military forces crushed these demonstrations on June 4, 1989, they also crushed the surge in creativity that had thrived throughout the decade (see Tiananmen Square Protest). As economic reforms removed state subsidies from many literary publishers, large numbers of writers were forced to pursue more commercial activities to support themselves. In this environment, the most successful writer was Wang Shuo, author of Wan di jiu shi xin tiao (1989; Playing for Thrills, 1997) and Qian wan bie ba wo dang ren (1989; Never Take Me For Human, 1999). Both celebrated and criticized for his irreverent novels of life in the burgeoning market economy of China, Wang ridiculed the pretensions of the cultural elite and explored his characters' longing to believe in a world of fantasy. It appeared that the intense creative energy found in Chinese literature in the 1980s had been exhausted by the 1990s, as writers retreated from their early ambitions or emigrated overseas. Their efforts continued to be recognized by the international community, however. One prominent example is Gao Xingjian, a modernist writer and literary critic who had suffered through government censorship in China in the 1970s and 1980s and emigrated to France in the early 1990s. In 2000 Gao became the first Chinese-language writer to be awarded the Nobel Prize in literature. Gao's major work, the novel Ling shan (1990; Soul Mountain, 2000), depicts the writer's journey through the Chinese countryside, encountering scattered shamans and the remnants of Daoist believers that suggest a collective unconsciousness. The award brought renewed attention to Chinese literature, which continues to diversify and bring new voices forward. Contributed By: Edward M. Gunn Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.