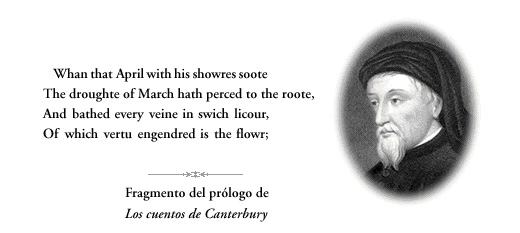

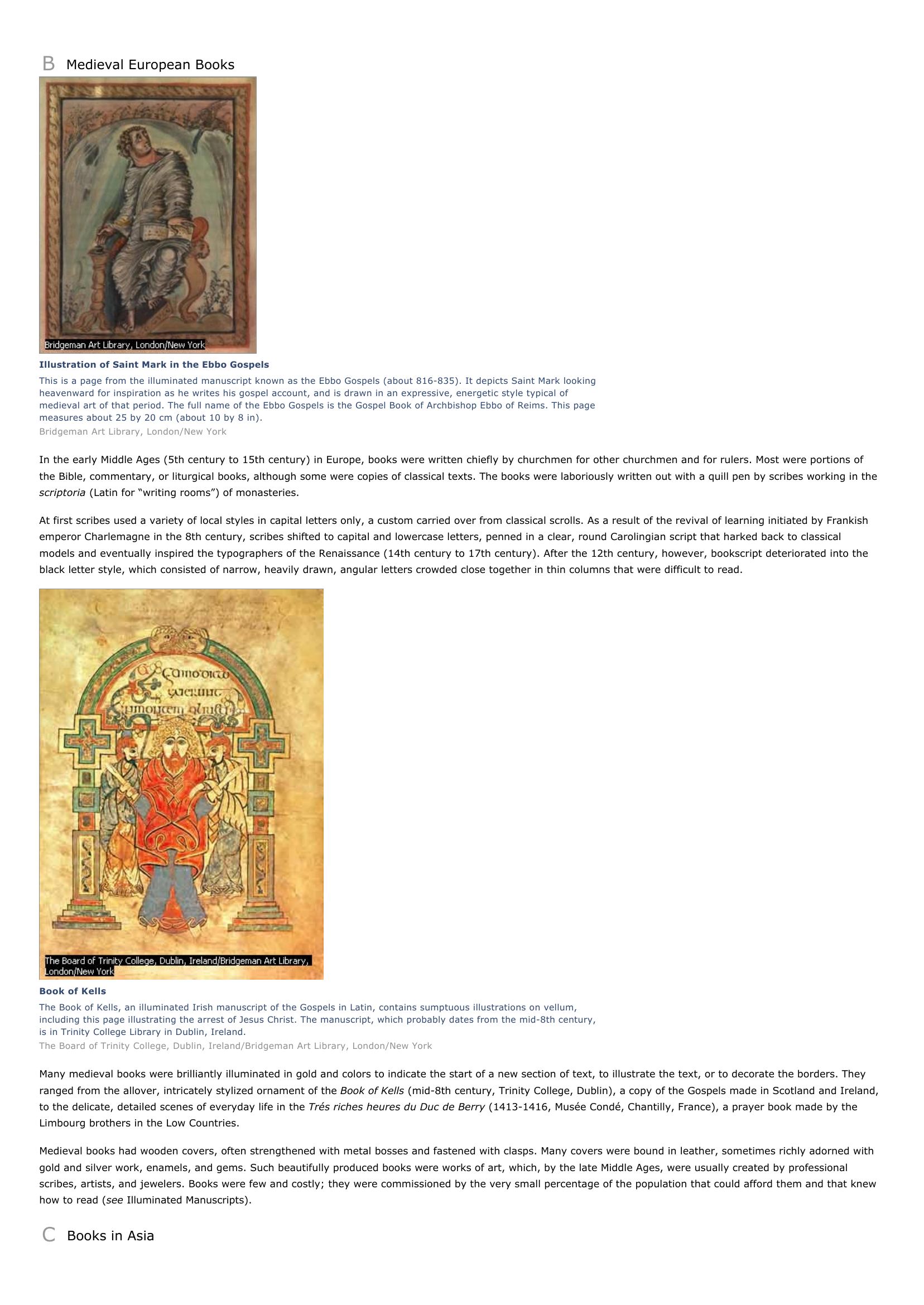

Book I INTRODUCTION Kelmscott Chaucer The Kelmscott Chaucer was published in 1896 by William Morris' company, the Kelmscott Press. The designs of Morris' books were influenced by medieval texts, but the actual type and floral decorative elements were Morris originals. The illustrations for this book were done by Edward Burne-Jones. Scala/Art Resource, NY Book, a volume of many sheets of paper bound together, containing text, illustrations, music, photographs, or other kinds of information. The pages are sewn or glued together on one side and bound between hard or soft paper covers. Because they are relatively durable and portable, books have been used for centuries to preserve and distribute information. A book is small enough to be carried around, but it is larger than a pamphlet, which generally consists of just a few pieces of paper. Books may form part of a series, but they differ from periodicals and newspapers because they are not published on a strict daily, weekly, or monthly schedule. Unlike a private diary, which may be in book form, a book is intended for public circulation. The term book is applied by extension to the scrolls used in the ancient world, even though they do not fit the modern definition of a book. In an editorial sense the word book can also refer to some ancient literary works, such as the Egyptian Book of the Dead, or to major divisions of a literary work, such as the books of the Bible. In the mid- and late 20th century, technological advances expanded the definition of the book to include audiobooks and electronic books, or e-books. Audiobooks are recordings made on cassette, compact disc, or downloadable computer programs. Electronic books are portable computerized devices that allow readers to download text and then read it, mark it up, and bookmark it. The term e-book is also used to refer to the concept of a paperless book, whether it is read on a specially designed e-book device, a personal digital assistant (PDA), or a desktop or laptop computer. II HANDWRITTEN BOOKS The forerunners of books were clay tablets, impressed with a writing instrument called a stylus, used by the Sumerians (see Sumer), Babylonians (see Babylonia), and other peoples of ancient Mesopotamia. Much more closely related to the modern book were the book rolls, or scrolls, of the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans. These scrolls consisted of sheets of papyrus, a paper-like material made from the pounded pith of reeds growing in the Nile Delta, formed into a continuous strip and rolled around a stick. The strip, with the text written with a reed pen in narrow, closely spaced columns on one side, was unrolled as it was read. Papyrus rolls varied in length; the longest surviving roll is the Egyptian Harris papyrus in the British Museum in London, 40.5 m (133 ft) long. Later, during the Hellenistic Age (4th century to 1st century BC), long book rolls were subdivided into a number of shorter rolls, about 10 m (about 35 ft) long, stored together in a single container. Scrolls were often covered with wrappings and tagged with the title and the author's name. Professional scribes reproduced works either by copying a text or by setting it down from dictation. Athens, Alexandria, and Rome were great centers of book production and exported books throughout the ancient world. Hand labor was slow and expensive, however, and books were owned chiefly by temples, rulers, and a few rich individuals. At the time, and for centuries thereafter, most people learned by listening to lessons or stories and memorizing them if necessary. Although papyrus was easily made, inexpensive, and an excellent writing surface, it was brittle; in damp climates it disintegrated in less than 100 years. Thus, a great part of the literature and records of the ancient world has been irretrievably lost. Parchment and vellum (specially prepared animal skins) did not have those drawbacks. The Persians, Hebrews, and other peoples of the ancient Middle East, where papyrus did not grow, had for centuries used scrolls made of tanned leather or untanned parchment. The production of parchment was improved by King Eumenes II of Pergamum in the 2nd century century A AD, BC; thereafter its use greatly increased, and, by the 4th it had almost entirely supplanted papyrus as a medium for writing. The Early Codex The 4th century also marked the culmination of a gradual process, begun about the 1st century, in which the inconvenient scroll was replaced by the rectangular codex (Latin for "book"), the direct ancestor of the modern book. The codex, as first used by the Greeks and Romans for business accounts or school work, was a small, ringed notebook consisting of two or more wooden tablets covered with wax, which could be marked with a stylus, smoothed over, and reused many times. Additional leaves, made of parchment, were sometimes inserted between the tablets. In time, the codex came to consist of many sheets of papyrus or, later, parchment, gathered in small bundles folded in the middle. These gatherings were laid one upon the other, stitched together through the folds, and attached to wooden boards by thongs. The columns of writing in codices were wider than those on scrolls and covered both sides of a parchment page. The codex made it easier for readers to find their place or to refer ahead or back. It was particularly useful for worshipers in religious services. The word codex is part of the title of many ancient handwritten books, especially celebrated manuscripts of the Bible. The Codex Sinaiticus, for example, is a 4thcentury Greek manuscript from Palestine that is now stored in the British Museum. B Medieval European Books Illustration of Saint Mark in the Ebbo Gospels This is a page from the illuminated manuscript known as the Ebbo Gospels (about 816-835). It depicts Saint Mark looking heavenward for inspiration as he writes his gospel account, and is drawn in an expressive, energetic style typical of medieval art of that period. The full name of the Ebbo Gospels is the Gospel Book of Archbishop Ebbo of Reims. This page measures about 25 by 20 cm (about 10 by 8 in). Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York In the early Middle Ages (5th century to 15th century) in Europe, books were written chiefly by churchmen for other churchmen and for rulers. Most were portions of the Bible, commentary, or liturgical books, although some were copies of classical texts. The books were laboriously written out with a quill pen by scribes working in the scriptoria (Latin for "writing rooms") of monasteries. At first scribes used a variety of local styles in capital letters only, a custom carried over from classical scrolls. As a result of the revival of learning initiated by Frankish emperor Charlemagne in the 8th century, scribes shifted to capital and lowercase letters, penned in a clear, round Carolingian script that harked back to classical models and eventually inspired the typographers of the Renaissance (14th century to 17th century). After the 12th century, however, bookscript deteriorated into the black letter style, which consisted of narrow, heavily drawn, angular letters crowded close together in thin columns that were difficult to read. Book of Kells The Book of Kells, an illuminated Irish manuscript of the Gospels in Latin, contains sumptuous illustrations on vellum, including this page illustrating the arrest of Jesus Christ. The manuscript, which probably dates from the mid-8th century, is in Trinity College Library in Dublin, Ireland. The Board of Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Many medieval books were brilliantly illuminated in gold and colors to indicate the start of a new section of text, to illustrate the text, or to decorate the borders. They ranged from the allover, intricately stylized ornament of the Book of Kells (mid-8th century, Trinity College, Dublin), a copy of the Gospels made in Scotland and Ireland, to the delicate, detailed scenes of everyday life in the Trés riches heures du Duc de Berry (1413-1416, Musée Condé, Chantilly, France), a prayer book made by the Limbourg brothers in the Low Countries. Medieval books had wooden covers, often strengthened with metal bosses and fastened with clasps. Many covers were bound in leather, sometimes richly adorned with gold and silver work, enamels, and gems. Such beautifully produced books were works of art, which, by the late Middle Ages, were usually created by professional scribes, artists, and jewelers. Books were few and costly; they were commissioned by the very small percentage of the population that could afford them and that knew how to read (see Illuminated Manuscripts). C Books in Asia Perhaps the earliest form of book in Asia was wood or bamboo tablets tied with cord. Another early form was strips of silk or paper, a mixture of bark and hemp invented by the Chinese in the 2nd century AD. At first the strips, written on one side only with a reed pen or brush, were wound around sticks to make scrolls. Later they were also folded like an accordion and stitched on one side to make a book, which was glued to a light paper- or cloth-covered case. The scholar-officials who wrote the books took great pains to develop distinctive styles of calligraphy, which was considered a fine art. III PRINTED BOOKS Frontispiece to the Jingangjing (Diamond Sutra) The Chinese translation of the Jingangjing (Diamond Sutra), a Buddhist text, was first printed from carved wood blocks in ad 868. This frontispiece to the book shows the combination of illustration and text; the illustrations were done by anonymous artists. The Jingangjing is the earliest known printed book. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Printing from carved wood blocks was invented in China in the 6th century AD. The first book known to have been printed from wood blocks was a Chinese edition of the Jingangjing (Diamond Sutra), a Buddhist text, dating from 868. The Tipitaka, another Buddhist scripture, which ran to more than 130,000 pages, was printed from about 972 to 983. Printing from reusable blocks was a much more efficient method of reproducing a work than was copying by hand, but each block took a long time to carve and could be used only for that one work. In the 11th century the Chinese invented printing from movable type, which could be reassembled in different orders for numerous works. They made little use of it, however, because the great number of characters required in Chinese writing made movable type impracticable. In Europe the printing of books from wood blocks, a technique probably learned from contact with the East, began in the late Middle Ages. Block books were usually heavily illustrated religious works with scanty text. A Renaissance Books Page of the Gutenberg Bible Completed between 1450 and 1456, the Gutenberg Bible was the first book printed after Johannes Gutenberg's invention of movable type. Originally intended to look like the work of a manuscript copyist, Gutenberg Bibles lacked page numbers, title pages, and other distinguishing features. Although the combination of papermaking and movable type made it possible to produce a large number of these Bibles, fewer than 50 original editions remain today. The illustrations seen accompanying the text on this page are probably hand painted, although many other drawings were printed using either a woodcut technique or etching. Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York In the 15th century two new technological developments revolutionized the production of European books. One was paper, which Europeans learned about from the Islamic world (which had acquired it from China). The other was movable metal type, which Europeans invented independently. Although various claims have been put forth for French, Italian, and Dutch inventors, German printer Johannes Gutenberg is usually given the credit. The first major book printed in movable type was the Gutenberg Bible, which was completed sometime between 1450 and 1456. These innovations simplified book production and made it economically feasible and relatively easy. At the same time, public literacy increased greatly, in part as a result of Renaissance scholarship and exploration, and in part as a result of the Protestant Reformation tenet that every believer should be able to read the Bible. Consequently, in the 16th century both the number of works and the number of copies of them increased enormously, further stimulating the public appetite for books. Italian Renaissance printers of the 16th century established traditions that have persisted in book publishing since that time. These included the use of light pasteboard covers, often bound in leather; regularized layouts; and clear Roman and Italic typefaces. Woodcuts and engravings were used for illustrations. Another tradition was the designation of book sizes as folio, quarto, octavo, duodecimo, 16mo, 24mo, and 32mo. These designations signify the numbers of leaves (each side counting as a page) formed by folding a large sheet of book paper. Thus, a sheet folded once forms two leaves (four pages), and a book made of sheets folded in this way is called a folio. A sheet folded twice forms four leaves (eight pages), and a book made of sheets folded in this way is a quarto. Modern European publishers continue to use these terms. Renaissance books also established the convention of the title page and the preface, or introduction. Gradually the table of contents, list of illustrations, explanatory notes, bibliography, and index were added. B 19th and 20th Centuries After the Industrial Revolution, book production became highly mechanized. The more efficient manufacture of paper, the introduction of cloth and paper covers, highspeed cylinder presses, the mechanical casting and composing of type, phototypesetting, and photographic reproduction of both text and illustration made possible in the 20th century the production of vast numbers of books at a relatively low cost. The subject matter of books became literally universal. The history and cultural influence of books also became a subject of scholarly study. Writers who explored various facets of the development of books include Canadian author Harold Innis (Empire and Communications, 1950), a pioneer in the communications field; Canadian writer Marshall McLuhan (Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, 1964), who argued that communications media profoundly shape the cultures in which they operate; American author Elizabeth Eisenstein (The Printing Press as an Agent of Change: Communications and Cultural Transformations in Early-Modern Europe, 1979), who explored the consequences in Europe of the transition from writing to printing; American writer Walter Ong (Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word, 1982), who examined the intellectual, literary, and social effects of writing; and English author Eric Havelock (The Muse Learns to Write: Reflections on Orality and Literacy from Antiquity to the Present, 1986), who studied the transition from the spoken to the written word in Ancient Greece. IV TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGES E-Book The concept of the paperless e-book became a reality in the late 1990s with the marketing of several devices. These machines allow users to download texts from the Internet and read them on a portable, handheld display. The RCA REB1100 model e-book shown here is about the size of a paperback. It lasts 20 to 40 hours between battery charges, holds a minimum of 8,000 pages of text, and includes an internal modem for downloading books. Thomson Multimedia In the 20th century, technological devices such as radio, television, motion pictures, tape recorders, computers, and CD-ROM devices challenged books as means of communication. However, because books are so easy to carry and care for, they remained a primary means for dissemination of knowledge, for instruction and pleasure in skills and arts, and for the recording of experience, whether real or imagined. Nevertheless, technology did have an impact on the book industry as people sought out new ways to experience and distribute information without using paper. Audiobooks were first marketed in the 1950s, and by the 1990s they had gained great popularity and were a major component of the publishing industry. Audiobooks are recordings of a person reading the text of a book. People can listen to them on cassette, on compact disc, or through programs downloaded from the Internet. They are popular in part because they allow people to experience books at times they cannot read, such as while driving a car. Also, people who are blind or have low vision can use audiobooks as an alternative to reading books with the Braille system. In the late 1990s several companies introduced electronic books, or e-books. These computerized devices display the text of books on a small screen designed to make reading easy. Electronic books are specially designed to be portable and light, and many models include a high-tech stylus that readers can use to highlight or make notes on the text. Booksellers and publishers sell e-books over the Internet in the form of computer files. A reader makes a purchase, then downloads the text to a personal computer or directly to an e-book device. Electronic books can store the same amount of information found in ten or more paper books, and they also offer some of the prime advantages of paper books--they are easy to carry and can be marked up. Many people believe that as e-books develop further in the early 21st century, they will challenge paper books in a way that 20th-century technologies did not. See also Bibliography; Bookbinding; Book Collecting; Book Publishing; Illustration; Library; Printing. Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2009. © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.